Mid-Autumn Festival took form in imperial palaces

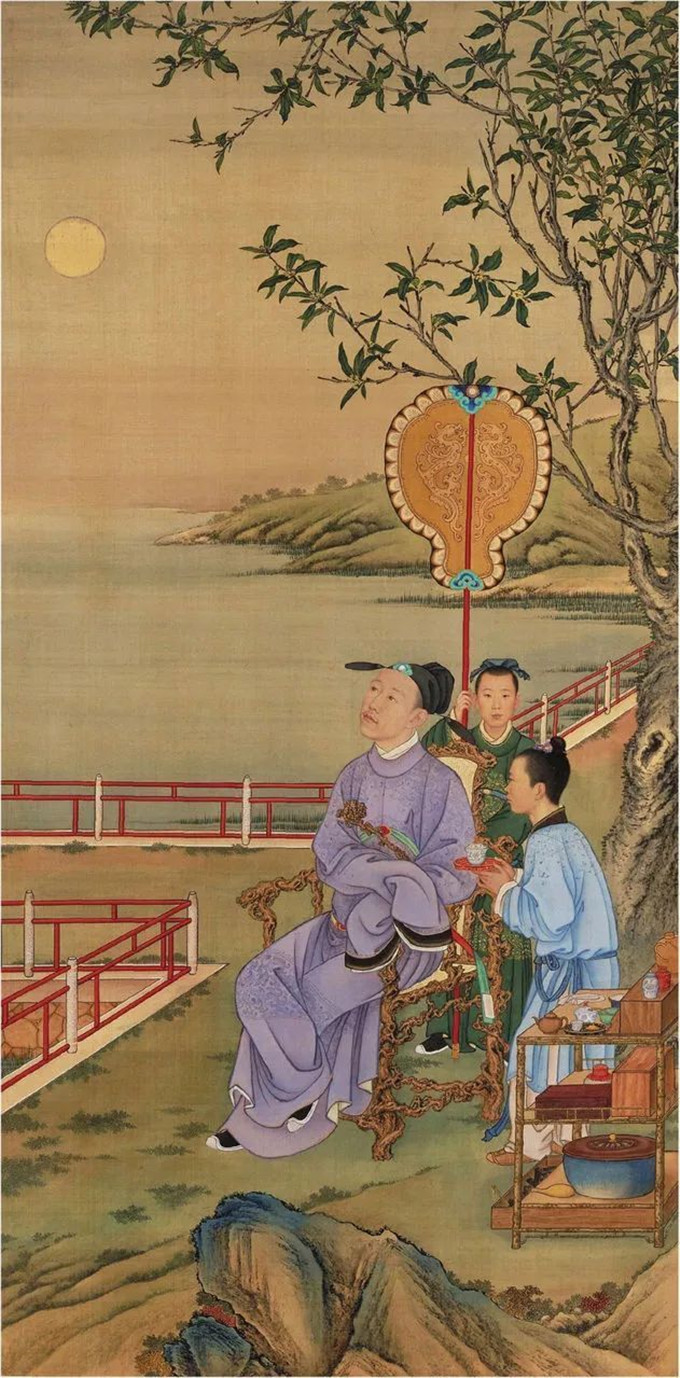

“The Qianlong Emperor Admiring The Moon” by an unknown artist of the Qing Dynasty Photo: FILE

It is generally believed that the tradition of celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival originated from the worship of the moon in ancient China. Rituals had been held in praise of the moon since the Zhou Dynasty (1056–256 BCE). It is recorded that the Zhou people practiced worship of the moon in quiet, low-lying areas. Descriptions of “Mid Autumn” first appeared in Zhou Li (Rites of the Zhou), a collection of ritual matters of the Western Zhou Dynasty (it describes the eighth lunar month as “Mid Autumn”). During the Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (202 BCE–220) eras, related rituals were mainly conducted by the imperial families. According to the Shi Ji (Records of the Historian), cattle should have been sacrificed to the sun while sheep to the moon. These sacrificial activities began during the reign the Emperor Wu of Han (ruling from 141 to 87 BCE).

Night banquet

Celebrating the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month as a festival can be traced to the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties, a period of material abundance and cultural blossoming.

Since the Tang Dynasty, the celebration of the day has taken on wider social significance and more customs for marking this occasion have formed. In the palaces, banquets became regular festive activities. A form of recreation called wan yue (playing with the moon), also known as admiring the moon, began to gain in popularity. It was Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685–762) who developed wan yue into an important practice of the Mid-Autumn Festival. According to Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi (Events of the Kaiyuan and Tianbao Eras), produced by the Tang scholar Wang Renyu, Emperor Xuanzong and his concubine came to admire the moon by the Taiye Lake on the night of the Mid-Autumn Day. The birthday of Emperor Xuanzong also fell on the same day as the Mid-Autumn Festival, making it a big day for grand feasts in the palaces. The famous dance, “Rainbow Skirt and Feathered Coat,” composed by Emperor Xuanzong, was first performed by Yang Yuhuan (the beloved consort of Emperor Xuanzong) at the feast. Wu ma (“dancing horse”) was another unique performance that took place during palace feasts at the time. It is recorded that on the night of the Mid-Autumn Day, Emperor Xuanzong ordered horse riders to instruct one hundred horses to dance in front of the Qinzheng Hall. When the dance ended, all the horses knelt down on the ground with a chalice in their mouths to congratulate Emperor Xuanzong.

It is said that the origin of the mooncake can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty. Folklore holds that a Turpan merchant presented an offering of cakes to Emperor Gaozu, the founder of the Tang Dynasty, in celebration of his victory over his enemies on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month. With a cake in hand, Emperor Gaozu pointed at the moon and said, “The Hu bing should be offered to the chan chu” (Hu bing refers to the cakes from the Hu people, or nomadic people; chan chu refers to a toad, which symbolizes the moon in traditional Chinese culture). Then he shared the cakes with his troops. Luozhong Jiwen, a collection of stories by the Song writer Qin Zaisi, mentions that Emperor Xizong of Tang found that the cakes he ate on the Mid-Autumn Day were quite delicious; so he ordered the palace kitchen to send the cakes in red wrapping to the newly graduated jin shi degree-holders (jin shi was the final and highest degree in the imperial examination in imperial China) as a reward. Thus, the mooncake may have originated from the imperial palaces.

The Mid-Autumn Festival became an established festival during the Song Dynasty. Mid-Autumn feasts in palaces became more grandiose, occasions in which emperors shared cakes with court officials and admired the moon together with them. The Song poet Su Shi also mentioned a moon-shaped cake filled with butter and barley malt syrup in one of his poems. Wulin Jiushi, an important source for urban life during the Song period by Zhou Mi, records a Mid-Autumn feast in 1182 in the Southern Song Dynasty. The feast was held in the Xiangyuan Hall by a pond. Inside the hall, the couch for emperors, screens and some other furnishing were all made of crystal. Spice of first-class quality contained in boxes filled the air with a pleasant fragrance. Outside the hall there was a lotus pond beneath the full moon. This was an excellent place for moon watching.

According to Wulin Jiushi, at the feast, 50 young girls played music on the southern bank of the lotus pond accompanied by 200 musicians from jiao fang (an institution to train musicians and singers) on the northern bank. The emperor invited officials ranked higher than the sixth pin (in imperial China, officials worked their way through the nine ranks titled pin; Nine was the lowest and one was the highest) to the feast. The father of the emperor chose a song and the consort of the emperor played a solo piece on the sheng (a Chinese free reed wind instrument usually consisting of 17 bamboo pipes set in a small wind-chest into which the musician blows through a mouthpiece). The emperor and the officials enjoyed the music and the moon until the late night. The last performance, “Ta Ge” (tap dance), brought the feast to its climax. Palace dancers in colorful dress swung their long sleeves, using their feet to create audible beats by rhythmically tapping the floor.

Temple of the Moon

In addition to the adoption of the rites of the Song Dynasty, the Yuan (1271–1368) palaces added more to the celebration of the Mid-Autumn Festival, such as the performance of fighting on water. As a people with a nomadic past, they also developed a game on horseback called zhui yue (chasing the moon). Under the moonlight, gamers ran after the moon on horseback in a spirited fashion.

Celebration of the Mid-Autumn Festival became more magnificent during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. Emperors practiced sacrificial rituals that were grander than ever. The Temple of the Moon, or Yue Tan, located to the south of the Fucheng Gate outside the old city of Beijing, was where emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties worshipped the moon. When the Jiajing Emperor of the Ming Dynasty ordered the enlargement of the city of Beijing, he decided to build an altar for the use of performing ritual sacrifices to the moon. The altar was named Xiyue Tan at that time. Its layout was similar to that of the Ri Tan (also known as Chaori Tan in the Ming and Qing eras, located outside the Chaoyang Gate), an altar designed for ritual sacrifices to the sun, but their appearances were quite different. Since the Chaori Tan was the place where emperors worshipped the sun, its altar was decorated with red glazed tiles, symbolizing sunshine. The Xiyue Tan was designed with white glazed tiles to resemble moonlight.

Apart from the ritual ceremonies at the Xiyue Tan, the imperial family of the Qing Dynasty also practiced rites for the moon within their palaces. On the Mid-Autumn Day, there was an altar that was used in the Hall of Heavenly Purity (the emperor’s principal residence). In the center of the altar laid the yue guang ma er, a piece of paper containing the images of the Taiyin Xingjun (the Lady of Yin and Goddess of the Moon), Bodhisattva and the Jade Rabbit, a mythological animal that lives on the moon and accompanies the moon goddess, Chang’e, constantly grinding a mortar and pestle to make the elixir of life for her.

The article was edited and translated from Beijing Evening News.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE