19th-century American literature: conflict between artistic ideals and social reality

old-picture

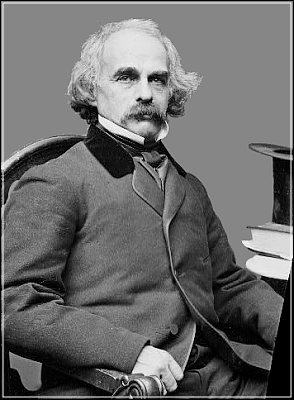

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a representative of 19th-century American writers.

Benjamin Franklin, in his autobiography, recalls that when young, he took a strong fancy to poetry. His father, however, discouraged his dream of being a poet, ridiculing his performance and telling him that “verse makers were generally beggars”. The American historical novelist James Fenimore Cooper, In Notions of the Americans, writes that traditional American values are not conducive to a thriving literary scene. He evinces that American society lacks the materials to inspire literary creation. Lack of copyright enforcement also enabled American publishers simply to pirate the works of European writers, further hampering the development of American literature. Herman Melville criticizes American writers’ blind imitation of European literature in Hawthorne and His Mosses, calling for the rebirth of national literature and national epics. In the preface of his short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse, Nathaniel Hawthorne says of the effect the idyllic life style of his country home has on its visitors, “What better could be done for those weary and world-worn spirits?” In his last novel, The Marble Faun, Hawthorne grumbles that America lacks the fertile cultural soil on which literary inspiration could be bred. Henry James shares these sentiments in his work of criticism Hawthorne. James maintains that American society is incapable of providing sufficient realistic sources to sustain its literary creation: it has no historical relics of comparable value to those in European that inspire reminiscence and nostalgia in an artist; and it does not have the kaleidoscopic of social life to nourish their poetic temperament and imagination. These are the main inspirational factors for writers.

The reflections of American writers on the limitations of their craft in their society show a country without deeply embedded historical and cultural traditions, or ample social fibers to offer support for its literature. A commercial society that values realism and efficiency may disdain literature and art. In this environment, American writers could neither grasp domestic understanding nor earn readers’ faith, let alone the support of publishers, all of which ultimately contributed to the sluggish pace of American literature.

Because of this difficult situation, the conflict between artistic ideals and social reality became one of the important subjects of 19th-century American literature. Stuck in the crevice between artistic ideals and social demands, American authors thought hard about the road of literary development and the path to self-redemption.

Artistic ideals versus commercial values

Washington Irving’s Rip van Winkle, the protagonist and namesake of the same-titled short story, is a good-natured man with an idealistic and slothful temperament. His “strong dislike of all kinds of profitable labor” brings him the frequent scorn of his nagging wife, but his disposition earns him the loyalty and friendship of his neighbors in all his domestic strife. It is in the picturesque mountains and rivers of the Catskills, however, where van Winkle seeks respite from his wife’s admonitions and restores a sense of spiritual freedom. Van Winkle can be interpreted as an image of the artist in early American literature. What he strongly aspires to is unfettered freedom—to escape from the fiercely competitive commercial society and heal his twisted and alienated spirit in nature’s embrace. Lacking the fibers of a literary society, however, America would hardly encourage this sort of artistic loafing and idling lifestyle. Irving himself, after living in Europe for 17 years, returned to his motherland only to find himself seemingly in exile.

A recurrent theme in Hawthorne’s short stories and essays is the conflict between artistic and commercial values. “Drowne’s Wooden Image” details the suffocation of a woodcarver’s creative impulse by commercial interests (note that the pronunciation of Drowne is the same as “drown”—the fate of the woodcarver’s talent). In “The Artist of the Beautiful”, Owen Warland, a watchmaker’s apprentice, overcomes the oppression of commercial consciousness. Like the author himself, Warland grapples with both external and internal pressures as he realizes his goal as an artist: firstly, he wrestles with and rises above mainstream America’s prioritization of the utilitarian over the aesthetic and the material over the spiritual; secondly, he transcends his own aspirations and ambitions to become an artist. Ultimately, he integrates his artistic ideals with his aesthetic perception of life. In short, Hawthorne defines the highest level of art through Warland’s character: to feel beauty through life and express beauty through art rather than to submit to the worldly standards of others. “The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle”, from Hawthorne’s final collection of short stories, describes an imaginative and affectionate snow figure through the pragmatic and matter-of-fact eyes of a hardware salesman, Mr. Lindsey who accidentally melts the snow figure after warming it by the fire. The subtitle, describing the snow figure, bears a touch of irony in satirizing the limitations of common sense and reason, as well as the consequences of blindly engaging in charity. It seems to hint to writers: literature and art, like the snow-image, can only be sustained in a cold social atmosphere; a cozy, materialized life will cause the artist’s sharp imagination and inspiration to melt away.

Melville’s short story “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” depicts a young, artisticlly-inclined man who takes a job copying legal documents. Wearied by the repetitive demands of his job, Bartleby begins to refuse requirements with the simple response, “I’d rather not.” Living in a society driven by speed, competition, efficiency and profit, his spiritual demands become unattainable and he dies in a hunger strike. Throughout the story, the word “strange” appears more than 20 times, demonstrating the narrator’s confusion and anxiety about how commercial society is destroying human nature.

Transcending social reality

After 20 years of novel writing that took on transatlantic subjects, Henry James turned his attention specifically to art and its creation in the 1890s, reflecting on the relationship between artists, society and life. A common theme of his works “The Death of the Lion” and The Lesson of the Master is that great artists should resist the temptations of fame and fortune and deal with the burden of marriage and family with caution. Both works suggest that the loftiest mission for the artist is constantly to refine their craft, which echoes the theme of Hawthorne’s “The Snow-Image”. “The Real Thing”, another short story by James, depicts the European and American cultural market at the end of the 19th century, portraying it as impervious to real art. Real artists, like aristocrats, no longer have a place in society, while genuine artwork and elegant writing count for nothing in a commercial society that prioritizes material gain. Artists are forced to set aside their dreams and comply with all of the demands society imposes on them, simply to survive. In a world defined by trade and void of cultural taste, the freedom of artistic creation has become a luxury.

The experiences and reflections of Hawthorne, Melville, James and other American writers depict the 19th-century American literary and artistic world as neglected and confined to the margins, given inadequate room to grow. Although the youthful nation’s cultural soil was ill-prepared for the seedlings of its future literature, its writers ultimately managed to break through this infertile ground. Through their assiduity, American literature emerged as a force for monitoring and questioning its own society, thriving and prospering at just the right moment. The spirit of literature is independent and autonomous, not cooperating or compromising. It expresses the persistence and beauty of humankind’s innate sense of what is right and wrong. In spite of the social and cultural milieu affecting the development of 19th-century American literature, the artist’s reflection, criticism, and transcendental spirit were able to overcome the obstacles holding back literature. Ultimately, American literature saved itself.

Dai Xianmei is from the Foreign Language School at Renmin University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 568, March 7, 2014

Translated by Bai Le

Revised by Charles Horne

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE