Women’s calligraphy in ancient China

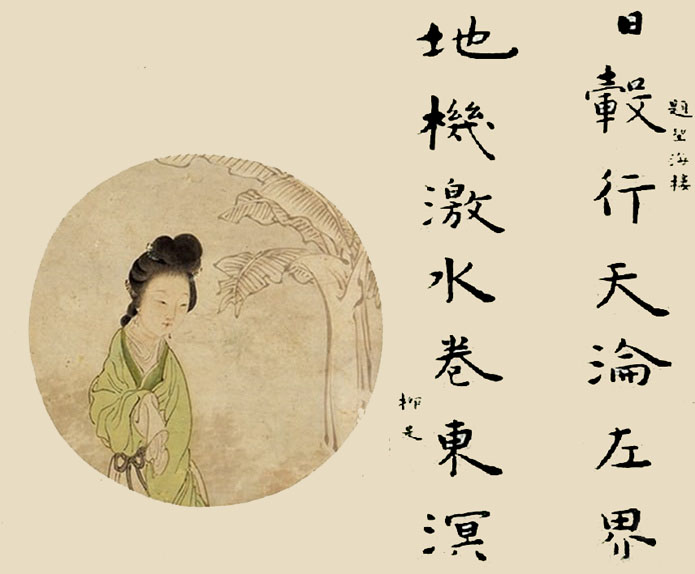

A portrait of Liu Rushi by the Qing artist Cheng Tinglu beside Liu's calligraphy Photo: FILE

Calligraphy written by women has a long history in China. Early references to women’s calligraphy date back to the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220). By the Tang and Song dynasties (618–1279), it had evolved into an active art. However, the art of Chinese calligraphy has long been dominated by men, and many outstanding works by women were neglected. In the Song Dynasty (960–1279), a woman once wrote some verse on the wall of a hotel. In the preface she asked the viewers’ pardon for women like her engaging in writing. This humble plea is evidence of the low status of women in the field of Chinese calligraphy at the time. Luckily, some brilliant women still left their mark in the history of calligraphy, and some museums have preserved their writing, reminding people of the honor that belongs to these women.

How did it begin?

The earliest female calligrapher was known as Qiu Hu’s wife (Qiu Hu was an official of the state of Lu) in the Pre-Qin period, who created a type of script named Diaochong Zhuan (literally, “carved worm seal script”). This type of script is named for its long, slim and twining strokes inspired by the shape of worms. Early records of Chinese women using ink brushes could be found in the Shi Jing (Classic of Poetry). In the poem “A Quiet Maiden,” it is mentioned that a maiden gives her lover a tong guan, an ancient name for the ink brush. According to the Hou Han Shu (Book of the Later Han), female officials were responsible for recording the achievements and mistakes made by rulers. These references served as evidence of women’s writing activities in ancient China.

It is said that Cai Yan, a female poet and musician who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), pioneered women’s calligraphy in ancient China. However, her handwriting has been lost, only leaving a few traces in the exchange of comments between the ancient literati of the time. A Tang scholar named Zhang Yanyuan mentioned in one of his works that Cai Yan’s father studied calligraphy from a genius and handed it down to his daughter. She in turn passed it down through Zhong Yao (a prominent calligrapher in the Eastern Han Dynasty) and the renowned female calligrapher Madame Wei of the Jin Dynasty, to finally reach Wang Xizhi (c. 303–361), who is generally regarded as the greatest Chinese calligrapher in history. Therefore, Cai Yan played a crucial part in the progression of Chinese calligraphy.

Women began to play a part in the field of calligraphy during the Wei and Jin Southern and Northern dynasties (220–589). The Wei Shu (Book of Wei), an important text describing the history of the Northern Wei and Eastern Wei from 386 to 550, mentioned that there were female officials that served in the palace, recording ritual activities and ceremonies. Gu Kaizhi (348–409), a celebrated artist of the Eastern Jin Dynasty, depicted a female official writing a document in his famous painting—“Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies.” Historical documents show that the social status of women had greatly improved during that period. They were valued not only by their virtues or manners, but also by their talent and knowledge. Many female intellectuals emerged, including those who were good at calligraphy.

Who are they?

Historical documents indicate that most female calligraphers that lived from the time spanning the Wei and Jin dynasties to the Yuan Dynasty were ladies in the palace and from prominent families. Conversely in the Ming and Qing dynasties, female celebrities and courtesans dominated the field of female calligraphy.

There were many ladies in the Tang palace known for their mastery of handwriting. Among them, Wu Zetian (624–705) was the best-known calligrapher. It is recorded that writing held a great favor with the female emperor, the only one in China’s long history. The epitaph of Princess Jin Xian (a princess of the Tang Dynasty) was excavated in 1974 in Shaanxi Province. What makes it unique is that the epitaph was written by Princess Jinxian’s younger sister, Princess Yuzhen. Epitaphs written by women are quite rare among all excavations made in China.

The periods of the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420) were characterized by the emergence of families with a strong calligraphy tradition. Female members of aristocratic families had more opportunities for education in the arts. Being aware of the trends in art and culture was considered crucial to self-cultivation. Despite the fact that the feudal system of the time and general social order placed heavy restrictions upon women, there were still some women who were able to travel through the country with their family members, and many wives of the literati matched the knowledge of their husbands so closely that both partners could foster the family’s cultural traditions together. Guan Daosheng (1262–1319), who married the celebrated calligrapher of the Yuan Dynasty, Zhao Mengfu, was also known for her handwriting. This couple greatly influenced the Zhao family, cultivating seven outstanding calligraphers, including Zhao Yong and Zhao Lin. Lady Guan was particularly known for her xingshu (running script) and kaishu (regular script), and her writing style was deeply influenced by her husband. Dong Qichang (1555–1636), one of the finest artists of the late Ming Dynasty, noted that it was almost impossible to distinguish Lady Guan’s handwriting from that of her husband, and none ever surpassed her for artistic transformation. Having produced many highly praised works of calligraphy, Lady Guan’s works were popular in the court. Emperor Renzong of Yuan used to collect Lady Guan’s works and said that he wanted later generations to know that in his court, there was a family in which the parents and sons were all masters of calligraphy.

Historical records show that there were 63 female calligraphers in the Song Dynasty, and 29 of them were born to prominent families. Of these female intellectuals, Li Qingzhao (c. 1084–1155) is perhaps the best-known scholar. It is said that Li was a master of writing, painting and ci style poetry. Anyone who read the preface that she composed for her husband’s book, Jinshi Lu, would have felt energized and refreshed.

In the Song Dynasty, the literati were usually accompanied by their concubines and maids when they read and wrote. Gradually, some smart concubines and maids became gradually more aware of reading and writing. Su Shi (1037–1101), one of China’s greatest poets and an accomplished calligrapher, recorded in his work that a concubine named Zhao Yun used to be illiterate. After marrying Su Shi, she started to learn writing and made remarkable achievements with kaishu.

Of the few courtesans who were known for their literary talent in the Tang Dynasty, Cao Wenji and Xue Tao (c. 768–832) were perhaps the most renowned women. It is said that Cao Wenji was obsessed with writing. She often wrote thousands of characters in one day, thus earning the nickname, Shu Xian, or the fairy of books. Xue Tao was an accomplished poet and calligrapher. Different from the soft and elegant strokes of female calligraphers, her strokes were praised as masculine, reminiscent of male calligraphers, revealing the style of Wang Xizhi.

When regarding the Ming and Qing dynasties, another woman stood out for her beauty and talent, despite her identity as a courtesan beyond the limits of what society considered a “good” woman. Her name was Liu Rushi (1618–1664), one of the “Eight Beauties of the Qinhuai River.” Her calligraphy was noted for its bold, masculine strokes, using the cursive script style (a style featuring characters written joined together in a flowing manner).

Features

Before the invention of kaishu, most women wrote words in the lishu style, or official style. (The Chinese word li here means “a petty official” or “a clerk.”) The strokes formed no circles and very few curved lines. As lishu style regulated the freedom of the hand to express individual artistic taste, kaishu was developed. Since then, most female calligraphers engaged in the kaishu style.

Most calligraphy created by women featured curved lines and delicate structures, a style reminiscent of feminine charm. However, there were some female calligraphers whose handwriting was as bold and strong as calligraphy made by men. It is noteworthy that people tend to praise calligraphy written by ancient women as “not feminine” or “very masculine.” This valuation is based on the traditional preference for the style of calligraphy considered typical of men.

Women had long been ignored in the history of imperial China. Their talents were overshadowed by traditional beliefs such as “it is the virtue of a woman to be without talent.” Luckily, some women still endowed the keenest sensibilities in their strokes, contributing to the richness of Chinese calligraphy.

The article was edited and translated from Guangming Daily. Yang Yong is from Nanjing University of the Arts.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE