Oriental charm of traditional Chinese clothing

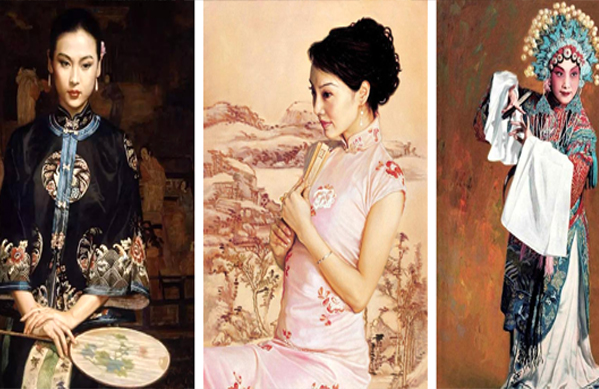

Three paintings by the renowned contemporary artist Chen Yifei (1946–2005) depict different styles of traditional clothing, including the tangzhuang (left), qipao (middle) and Chinese opera costume (right). Photo: FILE

China is unique when it comes to traditional clothing. This country began to apply silk to clothing about 4,000 years ago. In the 18th century, when the style of rococo swept through Europe, it was fashionable for upper-class people to wear Chinese style dress at balls.

Tangzhuang

In 2001, leaders from different countries wore tangzhuang in a warm-up performance at the APEC Summit in Shanghai. The distinctive style of those clothes caught on in global fashion. Tangzhuang is associated with the Tang Dynasty (618–907), a great era in imperial China, but the modern version bears no relationship to clothes of the Tang Dynasty. Naming this style of clothes after this glorious dynasty reflects the belief and respect invested in traditional Chinese culture.

Tangzhuang first appeared in the 20th century. It evolved from Manchu style clothing, particularly magua (a riding jacket once worn by Manchu horsemen), and adapts some elements of western clothing. Chinese director Li Shaohong exhibited various tangzhuang in her TV series, “The Orange is Red,” in which the heroine Xiuhe wears dozens of different tangzhuang. Those costumes were based on the clothes of princesses of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), together with the typical high-necked collar derived from modern clothing. Made from high-quality silk and finely embroidered with flowers by hand, these costumes look exquisite and elegant and are admired by many.

Generally speaking, tangzhuang feature four elements, known as dui jin, li ling, lian xiu and pan kou. Dui jin usually refers to the style of a jacket with a symmetrical opening. However, most of the tangzhuang for women are buttoned on the left or right, a design that not only conveys Chinese style but also looks graceful. The li ling is the mandarin collar with the front opening, displaying the charm of the elongated neck and highlighting the wearer’s demeanor. Lian xiu means that the suit and sleeves are made from one piece of cloth without seams between the sleeves and the main part of the suit. There are women’s suits that adopt the sleeves of the Qing princesses’ costume with cuffs shaped like horse hoofs, which look light and carefree. Pan kou, also known as Chinese knots, being hand-made, are used as buttons as well as decorations.

The designs and patterns are crucial to the tangzhuang, as they endow the clothing with strong oriental flavor. The most popular pattern was flowers in a helix, featuring peony, plum blossom, orchid, bamboo and chrysanthemum. They symbolize dignity or prosperity in traditional Chinese culture. Sometimes tangzhuang are embroidered with Chinese characters, such as fu (good fortune), lu (wealth), shou (longevity) or the double happiness symbol used for Chinese weddings. Today, Chinese people often prefer tangzhuang for some happy occasions or festivals to express their wishes for blessing and happiness.

Qipao

In the movie In the Mood for Love, the heroine wears 26 qipao, the colors and designs of which are refined and elegant, providing a chance for the world to appreciate the charm of Chinese women.

Designed by Shanghai people, the qipao (also known as cheongsam) gained popularity during the 1920s. Originating from clothes worn by Manchu women, it evolved by merging with the distinctive features of southern China’s clothing and Western patterns that show off the beauty of the female body. Sleeveless, slender and tight-fitting with a high cut, the qipao is very different from other traditional Chinese garments. Its side slits are repurposed into an aesthetic design that reaches the top of the thigh. Worn together with a mandarin collar, curly hair, high-heeled shoes, nylon stockings and brooches, it reflects the beautiful curves in a woman’s body and demeanor.

The qipao inherits the implicit and reserved beauty of traditional Chinese clothing. Yet its design is more vibrant and natural. It is more suitable for the figures of Asian women, exhibiting their grace and dignity. Different materials and color combinations make the qipao vary in color and style. The prosperity of the qipao has changed the usual stereotype of conservative Chinese clothing. Wearing a qipao nowadays has turned into something of a vogue style of dress, both at home and abroad. The qipao is no longer a garment particular to Chinese women but is adding to the vocabulary of beauty for women all over the world.

Wax printing

Wax printing refers to a technique used in a process for printing designs on cloth by putting wax on those areas of the cloth that should not be colored by dye, thus creating a special dyeing effect. It is the natural grace of batiks (a fabric printed by coating with wax the parts not to be dyed) that has enabled this technique to continue to thrive in China for about 2,000 years.

There were batiks traded through the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220). Wax printed clothes were also found among artifacts of the Northern Dynasty (386–581) unearthed in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. This technique matured during the Tang Dynasty. There are murals displaying the batik process in Grotto 130 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, Gansu Province.

Wax printing has long been a widespread technique in China. It can be traced all over the country. People in Guizhou Province apply this technique more than any other provinces in China. Batiks are one of the most favorite types of clothing of the women in Guizhou. Today, in some places within this province, women still wear clothes, headwear, aprons and skirts that are made of batiks.

To produce a batik, the first step is to draw patterns on white cloth with a copper knife and melted beeswax. After the beeswax cools, the cloth is soaked in a vat of indigo for dyeing, and then boiled in hot water to get rid of the beeswax. After removing the beeswax from the cloth, white designs are left on the cloth against its blue background.

Wax printing could create amazing “ice crack” patterns. This is because the beeswax can crack when it cools. These tiny cracks would be dyed during the dyeing process, thus leaving patterns on cloth similar to ice cracks. These patterns are not artificial but naturally formed. This natural beauty is the soul of batiks.

Chinese opera costumes

Chinese opera costumes play an important role in Chinese fashion. Developing from the daily wear of Chinese people, opera costumes embody many characteristics of traditional Chinese clothing.

Chinese opera costumes are as important as the characters themselves because each piece functions to distinguish the character being played. For example, the roles of dan (the general name for female roles in Chinese opera) are divided into qingyi and huadan according to their costumes. Qingyi (black dress, literally) are heroines, often referring to the role of dignified, serious and decent ladies in an opera. They are normally mature or married women. The roles’ dresses are simple and elegant, featuring black zhezi (a basic gown with varying levels of embroidery). This is from where the name of qingyi is derived. Different from qingyi, a huadan (flowery role, literally) is a lively, vivacious young female character, dressed in bright and colorful costumes. They normally wear short blouses and skirts, together with sleeveless jackets and waist sashes with ornaments. The costumes of huadan are the most beautiful of all opera costumes.

The design of Chinese opera costumes highlights the personalities, identities and moods of the roles. Take qingyi as an example. Most qingyi roles live a hard life and they tend to be gloomy. Therefore, they are usually dressed in cooler colors. On the contrary, the costumes of huadan are bright and gorgeous, which match well with their cheerful personalities.

Chinese opera costumes also serve as a mirror of traditional aesthetics. In the opera Slopes of Changben, when Liu Bei is chased by Cao Cao’s army and flees for his life, Zhao Yun, one of Liu’s generals, ventures alone into the enemy to rescue him. In order to highlight Zhao’s valiance and heroic bearing, the role’s face is usually painted red, symbolizing loyalty and heroism. His costumes include a splendid robe, a cape with dragon patterns and four triangular flags attached to his back (attaching four flags to the back indicates the wearing of full armor). With his movement, the flags waving and ornaments glimmering, the image of a valiant hero is vividly portrayed on the stage.

The article was edited and translated from Insights into Chinese Culture. Ye Lang and Zhu Liangzhi are professors at Peking University.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE