Communication of Chinese literature overseas gains increasing attention

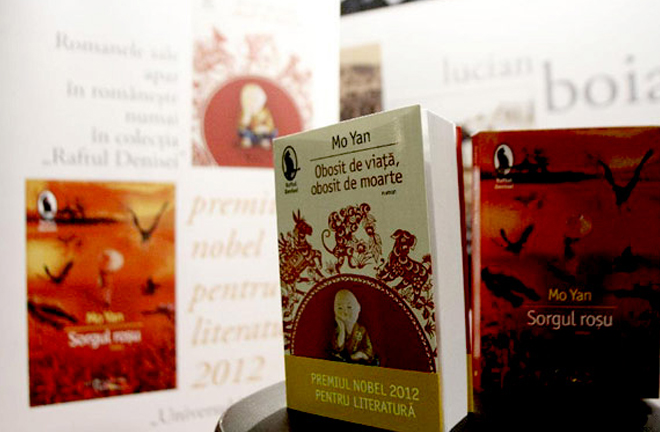

The Romanian version of Chinese writer Mo Yan’s novels is showcased at the 19th edition of International Book Fair Gaudeamus, in Bucharest, capital of Romania. Mo Yan is the winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature. Photo: XINHUA

Since the 21st century, China has launched a wide range of projects to boost the international appeal of Chinese literature, such as China Book International, Communication of China’s Literature Overseas, and Contemporary Chinese Literature Translation and Promotion. While we actively reach out to global readership, overseas translators are also contributing in their own way. A batch of sinologists and foreign Chinese literature researchers and enthusiasts have translated the works of contemporary writers such as Mo Yan, Yu Hua, Su Tong, Jia Pingwa, Bi Feiyu, Wang Anyi, Mai Jia and Liu Cixin into multiple languages and spread them around the world.

Academia also closely tracks the progress and trend of Chinese literature’s overseas communication, striving to come up with better translation strategies and practices and optimize communication channels and effects. At present, new trends in the communication of Chinese literature abroad can be summarized as follows.

Cross-cultural communication

In recent years, the communication of Chinese literature overseas has undergone a change from focusing on “going out” to emphasizing “going in,” which mainly refers to the cross-cultural communication power of Chinese literature and also an indicator of the discourse power of Chinese culture.

According to the Influence Assessment on World-Renowned Books from China, Chinese contemporary literature has become the most popular type of book collected by overseas libraries, ranked high above historical books.

In addition to the size of Chinese literature collections in foreign libraries, the feedback of foreign readers and professional audiences is also an important index to measure whether Chinese literature is being widely accepted in the overseas market.

The Report on the Communication of Chinese Literature Abroad (2018) takes an in-depth look into the reviews of readers on the Amazon website and the book reviews and recommendation lists on Goodreads as case studies to illustrate the acceptance of Chinese contemporary literature by foreign readers since 2015. The book details the methods and paths through which Chinese literature connects with readers after “going out” through translation, and how it is becoming an integral part of the recipient countries’ literature systems.

At the same time, the communication of Chinese literature abroad has turned away from the traditional market in the English-speaking and Western world, emphasizing instead a global readership. As we can see, the export of Chinese literature to Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia, the Spanish-speaking world, the Arabic-speaking world, and countries along the Belt and Road such as the Netherlands, India and Russia, has also mushroomed.

Contemporary writers such as Mo Yan, Yu Hua and Su Tong are quite popular in Japan. Yu Hua and Mo Yan have also stirred up some heated discussion in South Korea. Italian readers love Chinese literature, especially Yu Hua’s novels, among which To Live and The Seventh Day won Italian literature awards.

In 2013, China and India signed a memorandum of understanding to promote bilateral translation. In 2015, Chinese works such as The Dust Has Settled, A Sentence is Worth Thousands, To Live, Life and Death are Wearing Me Out, White Deer Plain, and Qin Qiang were added into the translation project.

China and Russia made similar arrangements in 2013, agreeing to translate no less than 50 literary works into each other’s languages within six years. In 2015, the translation booklist was extended to 100.

Global popularity

While the communication of serious Chinese literature abroad is fruitful, other genres have also started to gain popularity. In recent years, science fiction, martial arts, online novels and other genres have been translated into foreign languages and widely applauded.

Chinese sci-fi bestseller The Three-Body Problem won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, sending ripples of excitement across China’s internet. It is the first time for an Asian writer to win this award, giving fame to Chinese science fiction.

In 2018, A Hero Born, the first volume of famous Chinese martial arts novelist Jin Yong’s Legends of the Condor Heroes, was published in Britain. British publishing house MacLehose commissioned the translation work to Anna Holmwood, a professional focused on Chinese-English literary translation. It quickly grabbed a wide readership in the nation. The copyright was later bought by the United States, Germany, Spain, Finland, Brazil and Portugal.

When the English version of Zhou Haohui’s Death Notice was published in the United States, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and NPR’s book review program all enthusiastically reported the news, attracting readers to Chinese mystery and detective fiction. Ma Jia’s Decoded and Plot Against were also popular in the West, creating a brief craze for suspense fiction.

The translation and communication of literary works plays an important role in shaping the image of a country. People can get an impression of a country from reading its literature. Overseas academic circles are gradually linking the study of literature communication with the building of a national image, and they are discussing the role of literary works in the construction of national brands.

Domestic scholars have also noticed this new trend and incorporated it into their academic research to explore the relationship between imagology and translation studies. The translation of Chinese literature has a clear correlation with China’s image, that is, the existing Chinese image determines, to a certain extent, the translator’s choice of contemporary literature and Western readers’ level of acceptance.

In this light, literacy works present a channel to disrupt and adjust the existing image of China. The acceptance of Chinese classical novels, Tang poems, Song ci and Yuan opera around the world has shaped the image of a prosperous China in history. The introduction of modern literature, represented by Lu Xun and Shen Congwen, show China with a strong sense of responsibility and poetic aesthetics. And contemporary literature paints a colorful image of China, especially in the writing about reform and opening up, military heroes, new farmers and white-collar women. In a way, they have worked to change the stereotyped image of China and show it as a modern, progressive, and dynamic Oriental land.

Writer-translator interaction

Due to an emphasis on the loyalty of translations, previous studies on the overseas communication of Chinese literature mainly focused on comparison and analysis between the translation and the original text to see whether it accurately conveys the meaning and feeling of the original text.

In recent years, the interaction between translators and authors, publishers and editors in the process of translation has attracted the attention of scholars. The academic research on the translation of Chinese literature has shifted from a static comparison between the original text and the translated text to a dynamic translation process. This shift has something to do with the establishment of the Chinese Literature Translation Archive abroad.

In 2015, the Chinese Literature Translation Archive was founded at the University of Oklahoma, which houses about 10,000 volumes from the Arthur Waley and Howard Goldblatt Collections and 10,000 plus archival materials from Waley and Goldblatt as well as Wolfgang Kubin, Wai-lim Yip and others. As Jonathan Stalling, the founder and curator, said, these materials will help researchers understand the translation process of literary works, go beyond the simple conclusions of “domestication” and “foreignization,” “loyalty” and “disloyalty,” and explore many other constraints in the translation process, pushing translation research to a deeper level.

In addition, understanding the process of text conversion can help to remove the barriers of Chinese literature’s acceptance in foreign countries and encourage Chinese literature appreciation and research.

For example, when it comes to Goldblatt’s translation, some scholars doubted his method of “revising and translating.” However, according to the documents he donated to the institute, he had dozens of correspondences with editors, authors, publishers, scholars and readers during the translation of Yang Jiang’s Six Chapters from My Life ‘Downunder’ (Ganxiao Liuji). When he and Lin Lijun translated Massage by Bi Feiyu, they raised hundreds of questions about the exact meaning of the original words and phrases, the cultural implications they carried, and even the inconsistency of the wording.

For certain moments of translation that do not seem to convey the essence of the original text, we can uncover what happened from question-and-answer exchanges between the translator and the author. For example, in Massage, Bi uses the idiom “tianhua luanzhui,” literally, “pretty flowers falling from the sky” to describe a person’s hands. Goldblatt consulted the writer and finally came up with the translation of “pretty hands” to describe the beauty of the masseur’s movement.

At present, though Chinese literature has made great achievements, it still has a long way to go. How to grasp the new trends and changes in the communication of Chinese literature overseas and guide Chinese literature’s “going out” and “going in” is a topic that we should pay close attention to in future academic research.

Jiang Zhiqin is from the School of Literature at Shandong Normal University.

edited by YANG XUE

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE