Health and Serenity: Dragon Boat Festival

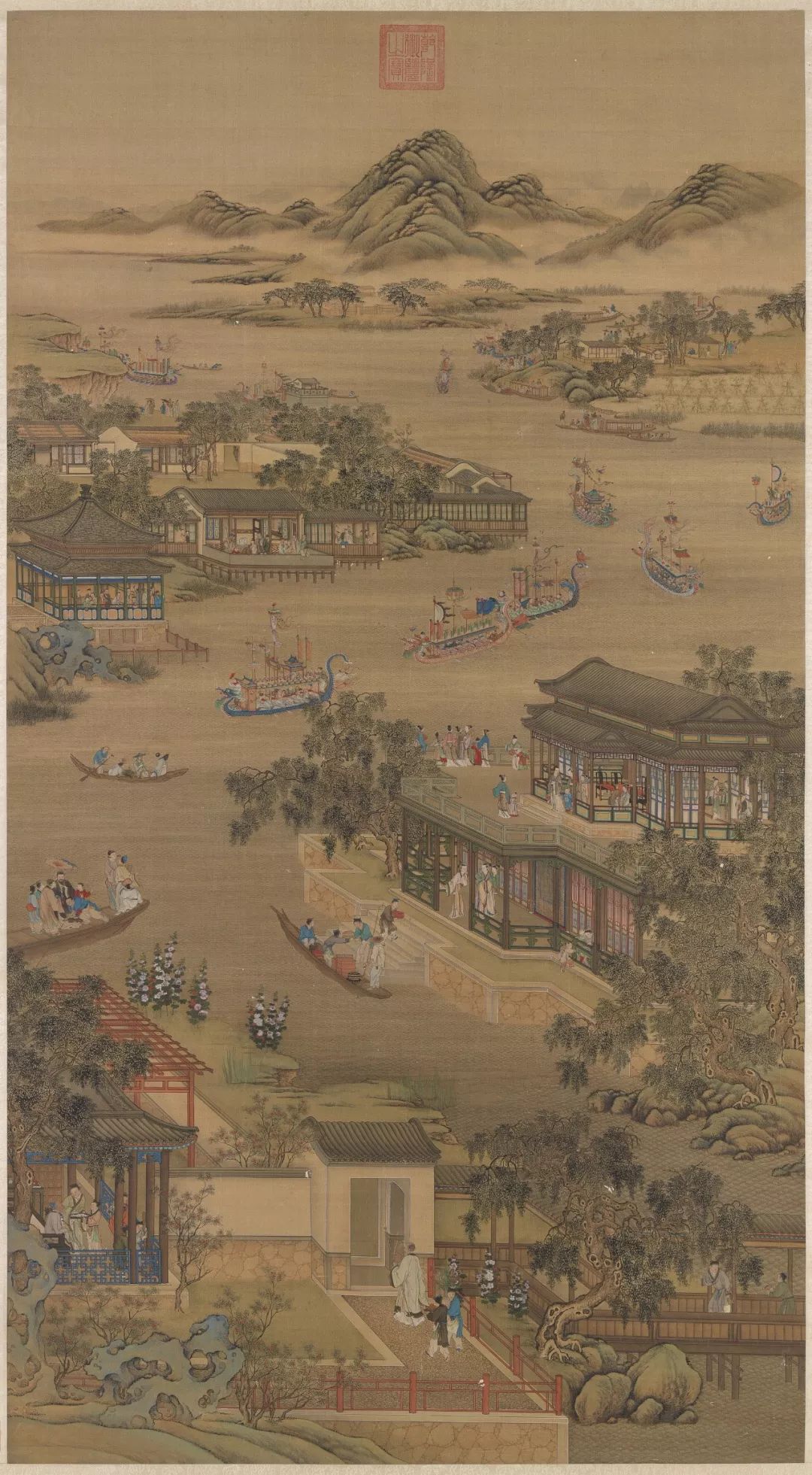

This is one of a set of paintings from the Qing Dynasty, depicting how the Qing people celebrated the Dragon Boat Festival. Photo: FILE

The Duanwu Festival, also known as the Dragon Boat Festival, falls on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese lunar calendar. It is a traditional holiday that commemorates the death of Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BCE), one of the greatest Chinese poets in the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE). Because of its tragic origins, the greetings of the Dragon Boat Festival do not start with “merry” or “happy.” Instead, people should say “Duan wu an kang” (May you have health and serenity) to each other on that day.

Origins

The earliest reference to the Dragon Boat Festival dates back to the Warring States Period. This day was originally associated with ancient superstition—the fifth month of the Chinese lunar calendar was considered an evil month and the fifth day of the month was a particularly bad day, so a lot of customs were built up, such as drinking realgar wine (The ancient Chinese believed realgar was an antidote to all poisons) and wearing a sachet stuffed with herbal medicines, which became the regular festival customs ever after.

Since the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern dynasties, the original motive to celebrate this day has become obscured. Some events add to the allure of this festival. The earliest record of eating zongzi on that day was found in the Xu Qi Xie Ji, a collection of folk legends by the Liang writer Wu Jun (469–520). The first text that mentioned dragon boat racing as a result of a movement to rescue Qu Yuan is from the Jingchu Suishi Ji, a description of festivals and seasonal activities of ancient southern China by the Liang writer Zong Lin. There are also some views that associate the festival with two other famous celebrities from history, Cao E and Wu Zixu. Wu Zixu (?–484 BCE), the honorable Premier of the state of Wu, was forced to commit suicide by his king, and his body was thrown into the river on the fifth day of the fifth month. Therefore, Wu Zixu was mostly commemorated in present southern Jiangsu Province, where the state of Wu was located. Some cities in present Zhejiang Province honor a girl named Cao E (130–143) on this day, who was said to have committed suicide in a river because her father was drowned in the river during a ritual ceremony.

Customs

Although the Duanwu is a national festival, specific customs vary widely in different places. Take the basin of the two mighty rivers in China—the Yellow River and the Yangtze River—for example. People living around these two rivers celebrated the festival in quite different ways.

Dragon boat racing is one of the most prominent activities of the festival. Dragon boats first appeared in the Warring States Period as a kind of vessel used in the south of China, the landscape of which is covered by many rivers and lakes. Based on the dragon warships along the Yangtze River, where dragons were considered the gods of rivers and seas, the boat was designed in the shape of a dragon. According to a research by the famous scholar Wen Yiduo (1899–1946), the dragon was the totem of the people in the states of Wu and Yue during the Spring and Autumn Period, where dragon-shaped boats were used to hold sacrificial ceremonies with the purpose of protecting people from floods. It was after the death of Qu Yuan that dragon boat racing was endowed with more significance.

Dragon boat racing was not so popular in the dryer climate of northern China. Instead, people had a shooting game to celebrate the festival, which was called sheliu (shooting the willow branches, literally). It is said that sheliu was originally a nomadic ritual ceremony to pray for rain in northern China. During the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234), it became a popular form of entertainment during important festivals. Participants shot willow branches with arrows from horseback and rushed to catch the fallen leaves. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, pigeons were put into gourds hanging on willow trees. Participants shot the gourds with arrows to let the pigeons fly out. The archer whose pigeon made the highest flight won the game.

In ancient beliefs, the fifth lunar month was a period when evil things came out. Therefore, taboos brought about various festive customs. In southern China, hanging mugwort and calamus on doors was a practice believed to keep evil spirits and disease away. In some places in northern China, especially the area of the Hexi Corridor, people used to hang willow branches on their doors, which served the same purpose as mugwort and calamus. As the most distinctive food of the day, the flavor of zongzi also varies in the north and the south. The shapes of zongzi range from being tetrahedral in southern China to an elongated cone in northern China. Northern style zongzi are usually sweet, filled with red dates or candied dates. In the south, zongzi have various flavors depending on the filling, such as salted duck egg or shredded pork.

Duanwu in Chinese literature

With a long history and rich cultural significance, the Dragon Boat Festival is often mentioned in Chinese literature. For most of the time, it reminds writers of their childhood or their hometowns.

Wang Zengqi (1920–1997) is a contemporary writer from Jiangsu Province. The lines in his books are filled with the elegant and tranquil charm of the regions south of the Yangtze River. In one of his texts, he mentioned that children often wore yadan laozi during the Dragon Boat Festival. A yadan laozi was a small woven net of colored string with a boiled duck egg inside. Wang wrote that the net was usually made by his aunt or sister on the day before the festival. On the morning of Duanwu, he stuffed the net with a boiled duck egg and hung it from a button on his coat. A yadan laozi was a child’s favorite accessory. They played with it during the festival and finally ate the duck egg.

Shen Congwen (1902–1988), one of the greatest modern Chinese writers, recalled the Dragon Boat Festival in his hometown in western Hunan Province. During the day of the festival, he wrote, all women and kids wore new clothes. People wrote the character “王” (Chinese character meaning “king”) on the foreheads of children with a mixture of wine and realgar. The most attractive aspect was the joyous occasion of the dragon boat racing on the river. Drummers usually sat in the middle of the boats. They played drums as soon as the boats set out, leading the paddlers through the race using the rhythmic drum beat. The performance of the team was more dependent on the pounding of drums. When the contest heated up, the area was immersed in the thunderous pounding of the drums and cheers from the riverbanks. This occasion is strongly reminiscent of the battle of the Song troops against the Jurchens on the Laoguan River in 1129, when the female general Liang Hongyu directed the Song soldiers with her drums and led the charge into the enemy formation.

The female writer Lin Haiyin (1918–2001) is known for her writings about old Beijing. She recalled a common festive toy for girls in northern China in one of her works. It was a pyramid-shaped toy made of colorful thread. To make such a toy, one needed to make a pyramid-shaped model from cardboard and then twine it with thread. Lin wrote that what pleased her most was to select the colored thread at her pleasure. She often made the toys ahead of the festival and sent them to her friends or hung them in her house. Girls also made various-shaped sachets with scented filling. These tiny sachets and pyramid-shaped toys were strung together with silk thread and tied to the front of girls’ garments as an ornament. Girls walked around with these ornaments proudly and happily.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE