Four ways Song culture enlightened China

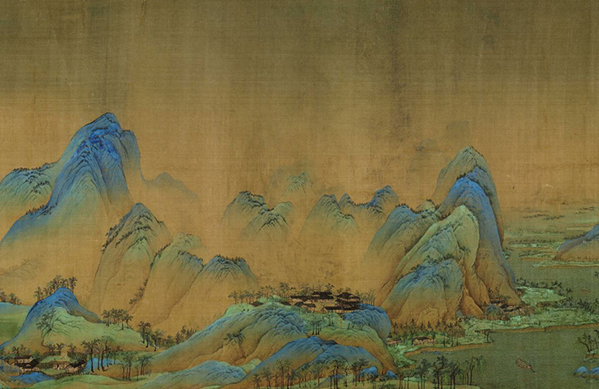

A detail of “A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains” by Wang Ximeng, a Northern Song artist Photo: FILE

It is a misunderstanding that the Song Dynasty (960–1279) was a period of weakness. In fact, based on the prosperous economy of the previous dynasty, the social productivity of China reached a higher stage of progress during the Song era. This dynasty was culturally the most brilliant era in later imperial Chinese history. Essays, poetry, calligraphy, painting, novels and plays flourished over the course of the Song. Its culture continues to influence modern China.

Literature is the vehicle of ideas

Learning from the failure of the previous dynasty where the rise of regional military governors overrode the power of the central government, the Song staffed its government with well-educated people through a policy that focused on favoring civil governance over military preparedness. Educated people became more politically active than ever. They were characterized by a high sense of social responsibility and intensive political involvement. Upon the influence of the prominent philosophy, neo-Confucianism, scholar-officials focused upon the discussion of philosophical ideas and defended Confucian principles. In the Song writings readers are often confronted with a series of reflections on philosophy and statecraft.

In the Song era, scholar-officials were driven by a strong sense of mission, considering literature as an essential way of spreading political philosophy and moral values among people. Although the Tang scholar Han Yu was the first to come up with a new interpretation of the relationship between writing and moral values, this idea didn’t have a wide influence on society until the Song era, when a philosopher named Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) expounded on the principle of literature serving as a vehicle of ideas. This Confucian statement was essentially a set of values, giving priority to the social and political significance of literature over its aesthetic values. The Song intellectuals concluded that literature was like a vehicle while ideas were like goods loaded on it, and that literature was nothing but a means and a vehicle to convey Confucian ideas. Upon this standpoint, Song thinkers and writers stressed the social role of literature and were eager to convey concerns about contemporary politics and state affairs in their writings.

Patriotism

Confucianism emphasizes that individuals should have a sense of social duty and the awareness of hardship. This idea was deeply rooted in the minds of the Song scholar-officials. They had a strong sense of duty towards the state and its people. Their ideal personality could be epitomized by the famous saying of the Song poet Fan Zhongyan—“To be the first in the country to worry about the affairs of the state and the last to enjoy oneself.” Unlike the previous dynasties—the Han and the Tang—which were considered to be some of the most successful dynasties in China, the poor performance and military weakness of the Song meant it was constantly threatened by strong rivals on its borders. During the earlier phase of the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127), the Song failed to recapture the Sixteen Prefectures, a territory in northern China under Khitan control since 938 that was traditionally considered to be part of China proper. In the south, Huanzhou, a region where criminals were exiled in the Tang Dynasty, was occupied by a dynasty of Vietnam. In the 12th century, the Song Dynasty was forced by the Jurchens to cede its entire northern region and retreat south of the Yangtze River and establish the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). Ongoing invasions and political strife cultivated a deep concern about the state’s future among educated people. This factor contributed to a distinctive trait of Song literature—patriotism.

The Northern Song court was forced to provide tribute to the Khitans and the Western Xia in order to achieve cessation of border clashes. This was a huge humiliation for the Song scholar-officials. Many successful works dealing with defending the country against enemies emerged. Even in the ci poetry, dominated by the genre of delicate restraint, people still heard the resonant voices from open-minded poets such as Su Shi, whose ci poetry was characterized by heroic sincerity and profoundness—“In time aiming my arrow at th’Wolf in th’northwest, My bow into a full moon I shall bend!” (trans. Zhuo Zhenying). During the 150 years of fighting against the Jurchens and the Mongols, patriotism became the main theme of Song literature. Writers expressed their sorrow at the harsh reality of the times through their poetry. The works of Lu You and Xin Qiji represented patriotic literature at its greatest heights. Both poets imbued contemporary literature with refreshing heroism and virility. The Southern Song literature, which was represented by these two poets, was a mirror of the contemporary social reality and reflected people’s longing for peace.

Inheritance and innovation

The Tang (618–906) and Song dynasties were the golden ages of Chinese classical literature in general, and poetry in particular. Tang poetry was regarded as a revered model for the Song poets. However, the Song poets didn’t copy the achievements of the Tang poets, instead developing their own features that equalled their predecessors in every respect. Though Tang poetry explored society almost down to the last detail, the Song still took up topics that have been overlooked in previous scholarship by writing about the more domestic moments of daily life. For example, Su Shi once composed poems for farm tools while another scholar named Huang Tingjian often talked about tea in his writings. In contrast to the Tang poets, the Song poets observed the world with a stronger appreciation for the details of their daily lives. The main roles in their writings were not heroes but common people.

High and low arts

The Song Dynasty is particularly noted for its great artistic achievements, which were roughly classified into forms of high and low arts. Poetry, painting and calligraphy that were popular among the scholar-officials continued to thrive as the orthodox arts. They represented a refined taste and reflected what conformed to the mainstream ideology. Meanwhile, the emerging burgher class, which came about through the prosperity of cities and advanced economy, became the major consumers of popular arts, or low arts. People enjoyed various social clubs and forms of entertainment in the cities, boosting the rapid development of vulgar amusements. There were puppeteers, acrobats, theatre actors, storytellers and places to relax. The high and the low arts met the needs of different social classes and reflected their different aesthetics. Their coexistence was an important symbol of a sound civilization. Moreover, it became a trend for people from both sides to borrow the best from each other, thus further spurring the growth of the Song culture, enriching cultural life and leading to more diversified artistic expression. Huaben, or storytelling, referred to a novella catered to the mass-market. Although written mostly in vernacular language, huaben sometimes included simple classical language. For example, a huaben named Nian Yuguanyin started with 11 poems from Su Shi and Wang Anshi, who were generally considered the representative scholars of the high arts.

During the Song era, the incorporation of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism profoundly shaped the personalities of the scholar-officials to an extent that was quite different from before. They began to have a tolerant attitude towards low arts and tried to incorporate the best of high and low arts in their works. Their attitude towards the world was revolutionary. In their mind, social duty and individual freedom were no longer mutually exclusive. By contrast to the Tang people who were preoccupied by the excitement of faraway adventures and were very open to the outside world, the Song intellectuals looked inward. They observed the world close to them with calm and discerning eyes. With a stronger appreciation for the virtues of modesty and harmony, Song intellectuals engaged in a philosophy that focused on basic principles rather than details when dealing with the choices of high or low arts. They also preferred to neglect formalities in favor of essence. Therefore, in their eyes, one didn’t need to give up alcohol and meat to become a Buddhist, and staying away from human society was not an essential prerequisite for a reclusive life. These thoughts liberated scholars from the either-or situation of “high or low.” They could express their sense of political involvement via prose and poems, while their sentiments about immediate daily life, which were less serious, could be confided through ci poetry.

These four aspects are only some of the reasons for the booming culture of the Song era. It is important to absorb the best from the cultural achievements of the Song Dynasty.

This article was edited and translated from People’s Daily. Mo Lifeng is a professor at Nanjing University.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE