Aesthetic trends of Six Dynasties era

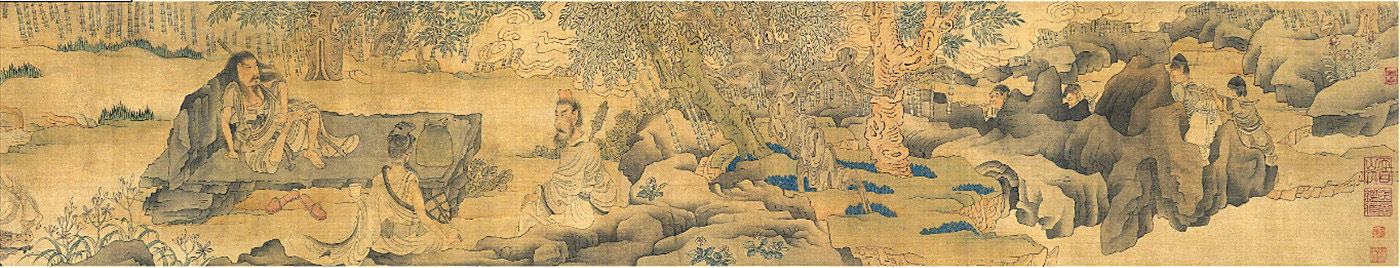

A detail of “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove” by the Ming artist Chen Hongshou (1599–1652) Photo: FILE

The Six Dynasties era was a flourishing period for literature and the arts. Various artistic movements stimulated complex ideas of beauty. Aesthetics of that period were characterized by three trends, known as the act of nobility, Xuanxue and cultural fusion.

Act of nobility

During the Six Dynasties era, great aristocratic families began to arise, establishing firm control over Chinese society. The dominance of aristocratic families deeply influenced people’s lifestyles. People tended to value the life of nobility.

Aristocratic people developed and followed particular rules of etiquette. Their customs and behaviors were considered the model of nobility. Influenced by this aristocratic etiquette, people in the Six Dynasties era paid great attention to their dress and manners. It is said that Cao Zhi (192–232), a prince of the state of Cao Wei, had to perform a set of activities before meeting a scholar named Handan Chun. These activities involved taking a bath, fu fen (an ancient approach to make-up), dancing hu wu (non-Chinese dances originated from Central Asia) with hair unbound and nude from the waist, and swordplay. After these activities, he dressed up and came to see Handan Chun. These activities had developed from the popular lifestyles of contemporary literati. In the mid-3rd century, a group of eccentric geniuses known as the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove retreated from the hypocrisy and danger of the political world to a life of drinking wine and writing verse in the countryside. They impressed the world with their carefree, unconventional manners and behavior, such as wearing rough clothes with hair disheveled, stumbling around naked and indulging in ecstatic experiences through alcohol and drugs, especially the notorious Five Minerals Powder, which created psychedelic states and made the body feel very hot. These symbolic manners and ways of acting have worked profound changes upon Chinese culture.

The aristocratic class believed that it was their cultural heritage and customs that enabled their clans to continue to thrive. Therefore, they valued education and cultural literacy. There were several talents that ranked high in cultural literacy: being accomplished in the classics; having a good command of the Daoist canon and qing tan (literally known as pure conversation, an activity involved witty conversation about metaphysics and philosophy that took place among political and intellectual elites); being good at literature, music, calligraphy or painting; being acquainted with the game of Go and medicine or other talents. The massive literary legacy that had been handed down since the pre-Qin period accounted for a major source of knowledge in the Six Dynasties era. Being able to understand and interpret these classics was a standard of the literati. Qing tan, the most important aesthetic movement during the Wei-Jin period, was essentially a competition of knowledge and intellect.

A keen intellect and wit was also highly praised in contemporary society at the time. Being witty and quick to understand things was essential to social activities such as intellectual discourse and playing the game of Go. Because of the heavy emphasis on intellect, people from the aristocratic class were often engaged in things that didn’t take much physical effort, and a martial spirit tended to be spurned. As a result, an image of frailty associated with the intellectual was established and has been influential in shaping the aesthetics of the Chinese people ever since.

Xuanxue

Xuanxue, a metaphysical philosophy that grew in the Six Dynasties era, was a dominant trend of thought, spreading from its status as a philosophy to a value and belief that deeply affected people in that era. Based on the Daoist canon, Xuanxue was concerned with the relationship and nature of Being and non-Being, and stressed the free expression of human nature and emotions. Under the influence of Xuanxue, people found beauty everywhere. They chanted about the charm of nature and preferred love to traditional etiquette. Literature and arts were put in a higher position and flourished. Aesthetics in the Six Dynasties era showed an unorthodox attitude towards the world.

This attitude didn’t focus on being useful and practical but was more concerned with beauty and art. People paid more attention to the charm of personal traits than general material importance. Scholarly discourse occurred for the purpose of enjoying the views of speakers, literary talent and the abilities of analysis and the elegance of interaction. When it came to nature, people enjoyed its enchantment and tried to understand nature instead of owning it. Drinking and appreciating the arts were also aimed at gaining poetic experience and achieving an unworldly beauty. Objects or things that were characterized by being simple, remote, bright, smooth or refreshing were highly valued. This understanding of beauty laid the foundation for the aesthetics of the traditional Chinese arts and is still influential today.

Cultural diversity and fusion

As a result of the disintegration of the society and constant migration, contacts between the Han people and various non-Han ethnic groups stimulated cultural rivalry and fusion. Inevitably, the changes and uncertainties of the age were reflected in the aesthetics.

The Han Chinese found themselves in cultural conflict and fusion with two civilizations—one from the Central Plain in the north, and the other one from the Jiangnan area in the south. The Three Kingdoms was the tripartite division of China among the states of Wei, Shu and Wu. Although the state of Wei claimed itself the orthodox regime of China, the state of Shu considered itself the extension of the Han Dynasty, which was the acknowledged orthodox regime of China. Meanwhile, the state of Wu established its own sovereignty in the Jiangnan area and joined the competition for supremacy over China. Most of the communication among them was through political or martial movements.

Cultural rivalries emerged when the Jin court escaped from the nomad invaders and reestablished their government in southern China. Large numbers of Chinese fled south from the Central Plain, causing the gradual shift in Chinese civilization from its earlier northern centre to the less populated southern zone. Noticing huge differences in languages, diets, customs, habits and arts, the outsiders and the locals observed and occasionally mocked each other. Soon, however, people from the north began to understand and accept the local culture. As a result of the confusion, a new culture formed and began to dominate the Jiangnan area.

The period between 420 and 589 in Chinese history is conventionally called the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, when northern China was politically separated from the Chinese dynasties established in Jiankang (known as Nanjing today), leading to a wide diversification of political thought and philosophy. The Daoism-oriented Xuanxue was highly influential in the Southern Dynasty and was viewed as the orthodox philosophy. Still, marked by the adoption of the Chinese language, costume and political institutions, the rulers in the north were ardent supporters of Confucianism. Lyrical and romantic poetry was popular in the south. In the north, where war was always near, martial influences appeared in poetry and were greatly appreciated.

At the same time, more complicated cultural communication occurred between the Han Chinese and nomad invaders. Northern China was ruled by a series of dynasties founded by invaders from central Asia, including the Xiongnu, Jie, Xianbei, Di and Qiang. Most of them maintained their own social customs and practiced native religions while adopting the Chinese way of life. Tuoba Hong (467–499), an emperor of the Xianbei-led Northern Wei Dynasty, was said to be heavily into studies of Chinese culture. The Han Chinese and the nomads that settled in northern China interacted and learned from each other. The comparative study of the aesthetics of the two parties is also an interesting task.

Li Xiujian is an associate research fellow from the Anthropology of Art Research Center at the Chinese National Academy of Arts.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE