Paradox of filial piety during May Fourth Movement

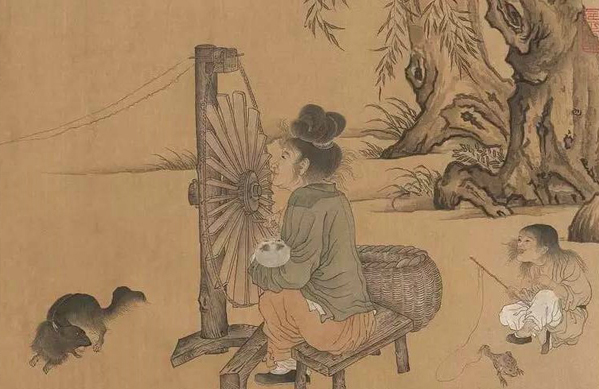

This detail of “The Spinning Wheel” by Wang Juzheng from the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) depicts a poor woman at a spinning wheel with a baby in her arms. She represents the image of a mother who has to support a family while taking care of her children. Photo: FILE

The heavy emphasis that Chinese culture places on filial piety has been criticized over the years. During the May Fourth Movement (1919), however, the bitter controversy over filial piety attracted immense public attention. Skepticism abounded in the fields of literature, philosophy and history. Many scholars attacked traditional Chinese ethics, to which the notion of filial piety was central. There was a strange phenomenon in this wave of anti-filial piety—some scholars and intellectuals, while criticizing this traditional Chinese moral, were in fact paragons of filial piety. This phenomenon was called the Paradox of Filial Piety. Three outstanding scholars of the time—Lu Xun (1881–1936), Hu Shi (1891–1962) and Fu Sinian (1896–1950)—were representative examples of this paradox.

Reasons behind criticism

During the time of the May Fourth Movement, educated people analyzed and criticized the notion of filial piety from various perspectives. To sum up, there were several reasons to abandon this moral standpoint.

The first reason was that filial piety was untenable. Traditional culture stressed the fact that parents give life to their children and subsequently support them throughout their developing years through providing food, education and material needs. Because of receiving all these benefits, children are thus forever in debt to their parents. In order to acknowledge this eternal debt, kids must respect and serve their parents. Lu Xun argued that producing offspring was merely out of animal instinct and “the son need feel under no obligation to his father.” Hu Shi thought that having children was not an intentional behavior and was without a child’s consent, so parents and children didn’t own each other. Similarly, Fu Sinian believed that filial piety was an obligation that was imposed on children by their parents.

The second reason was that the nature of filial piety was an inequality between parent-child relationships. In the text “What Is Required of Us as Fathers Today,” Lu Xun mentioned that “In China parents—especially fathers—wield great authority.” “Parental authority is considered absolute: Of course whatever the old man says is right, while the son is wrong before he opens his mouth.” The idea that one should always serve one’s parents or elders before younger generations, said Lu Xun, was a mistake based in selfishness, because it expected the younger generation to sacrifice itself for the elders’ sake. For them, this unequal relationship between parents and their children was a violation of evolution, because the later forms of life are always more significant and complete and the earlier forms of life should be sacrificed to the later.

With the third reason, they compared the notion of filial piety to religion. Hu Shi thought that Confucianism came up with the idea of filial piety because it didn’t believe in gods or ghosts, thus making parents as figures of authority to supervise later generations to do right things and punish wrong behavior. He said that Confucianism introduced its concept of parents and ancestors to function as a judge and a supervisor of people. Hu Shi recognized the moral function of filial piety while Lu Xun saw no moral value in the notion of filial piety.

The fourth reason lies in the belief that filial piety was a false morality. Lu Xun said that the desperate preaching of filial piety showed that in reality filial sons were rare, and this came about purely because men upheld a false morality and ignored true human feelings. Lu criticized the old ideas and old ways of filial piety, such as the systems in imperial China whereby filial sons could become officials, saying such systems “have achieved very little, simply making the bad more hypocritical and causing more useless suffering to the good.” He also drew several examples from the Twenty Four Acts of Filial Piety, a classic text of Confucian filial piety written in the Yuan Dynasty, to prove that some filial acts that had been praised were actually absurd and superstitious. One story he mentioned was about a man named Wang Xiang, whose stepmother asks for fresh fish in winter. Hence, Wang lies on the ice till it melts and catches a fish. In another story, a man named Meng Zong cannot find bamboo shoots in winter for his mother to eat. He weeps in a grove until bamboo shoots sprout from the ground. Lu commented that “when there is an end of superstition, there will be no more sons weeping beside bamboos or lying on the ice.” Hu Shi pointed out that the followers of Confucianism, in order to maintain parental authority, created many rigid codes of behavior and destroyed the true meaning of filial piety.

The last reason for them to disapprove of filial piety was because of its negative effect upon society. This hierarchical principle of elders over youth has been criticized as stunting and inhibiting young adults from making decisions that would allow them to grow as a person or have their own lives. Hu Shi said that rigid norms of filial piety made people shrink from taking chances, and he believed that the concepts about filial piety, together with traditional marriage and family, hindered social progress.

Marriage and filial piety

From these viewpoints, it might have seemed that these scholars would not have treated their parents with respect. In fact, however, they were filial sons in their families. Lu Xun had been working hard to support his family and help treat his sick father since age 13. He concealed his illness from his mother in the last few years of his life, just to soothe her. Their love and respect for their parents can be easily found in their writings and life experiences. Why would people with so much love for their parents and families attack filial piety?

Undoubtedly, these scholars’ viewpoints were based on the motivation to rebuild society and culture against imperialism and feudalism. Aside from this motive, their disapproval of filial piety lay partly in their own experiences, or, their discontent relating to marriage. In pre-modern China, marriage had been controlled by parents. Even in the early 20th century, getting married under the auspices of parents was still regarded as a practice of filial piety. Evidence showed that Lu Xun, Hu Shi and Fu Sinian didn’t love the women whom their parents asked them to marry, and they were dissatisfied with their marriages. The reason for them to accept such marriages was that they didn’t want to disappoint their parents or that they wanted to be filial sons. They seemed to criticize the general concept of filial piety, but what they truly objected to was the parental control of marriage. Lu Xun’s mother once said, “They (Lu Xun and his wife) neither quarrel nor talk much with each other. Living separately, they don’t look like a couple.” In fact, Lu Xun was suffering from an inner conflict. He thought his wife was also a victim of the arranged marriage. In a letter to his friend, Lu wrote that he was grateful to his mother for her care and love, thus sacrificing himself to make her happy. He told his friend that marriage was a gift from his mother, and the only thing he could do was to keep it, but he still didn’t feel love from his marriage.

Marriage tragedy doesn’t necessarily lead to direct criticism of filial piety. To understand the fierce attack on filial piety, the contemporary social circumstances should be taken into consideration. In that era, China was suffering from foreign invasion and a deep recession. Intellectuals blamed traditional culture for the rapid fall of China into a subordinate international position, and they maintained that China’s cultural values prevented China from matching the industrial and military development of the West. Also, influenced by the West, they called for a re-examination of Confucianism in a critical way and an end to the patriarchal family in favor of individual freedom. Therefore, the clan system and Confucianism, which were the foundation of traditional values and morals in China, became the target of criticism.

Obviously, some attacks on filial piety were a direct result of dissatisfaction with marriages. One of the more important reasons for people to live up to filial piety lay in their inner respect and love for their parents. Therefore, it is said that what the intellectuals in the movement should have objected to was performing filial piety rigidly and inflexibly obeying the wishes of parents. But the blame was generally laid on the nature of filial piety. The paradox of filial piety reflects the intellectuals’ inner conflict between emotion and intellect. They confused the acts of filial piety with the true meaning of this important moral and cast it aside. Traditional attitudes towards marriage that entitled parents to make decisions are no longer applicable in modern society. However, filial piety originates from human nature. It is natural to offer love, respect, support and deference to one’s parents and other elders in the family.

This article was edited and translated from the journal Literature, History & Philosophy. Huang Qixiang is a professor at Shandong University.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE