Translation and research of tea classic promoted Chinese tea culture to world

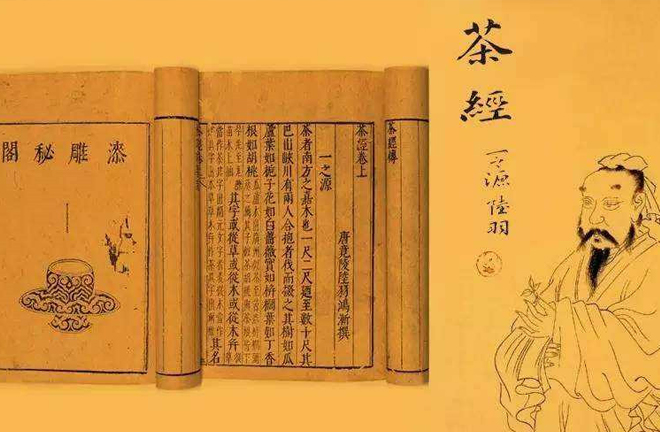

Tang Dynasty tea expert Lu Yu (733–804) and part of his magnum opus The Classic of Tea Photo: FILE

Tea is one of the main symbols of the Chinese culture. As early as in the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE–8 CE), tea and tea culture had been spread overseas. The Classic of Tea, also translated into Cha Ching based on the Wade-Giles romanization system, not only advanced the development of tea culture in China, but also generated extensive influence abroad. Authored by Tang Dynasty tea expert Lu Yu (733–804), who has been honored as the Sage of Tea, the masterpiece is the first known monograph on tea in the world. Studying the outbound transmission of tea culture in ancient times along with the history of the translation of The Classic of Tea will provide reference for the telling of Chinese stories and the dissemination of Chinese culture in the contemporary era.

Overseas influences

China was the first country in the world to grow tea on a large scale and foster a tea-drinking custom. The tea culture and its comprehensive system were brought into being in the Tang Dynasty (618–907), the heyday of economic, political and cultural development in ancient China, and The Classic of Tea came out during this period. The monumental book consists of three volumes and 10 chapters. Rich in content and graceful in writing, it laid the groundwork for the shaping of the Chinese tea science and tea ceremony. After its debut, the book was widely circulated abroad.

Japan received the earliest and most profound influence from The Classic of Tea. It was formally introduced into Japan in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). In the mid-12th century, Japanese monk Myoan Eisai came to China twice and took tea seeds and many documents related to tea culture back to Japan, including a handwritten copy of the tea classic.

The tea ceremony prevailed in modern Japan, when growing numbers of scholars began to explore tea culture. During the Edo period (1603–1867), Japan started to reprint The Classic of Tea, particularly the version edited by scholar Zheng Si from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). In 1774, Daiten Zenji made detailed annotations to the book using katakana and Chinese characters, composing The Detailed Classic of Tea.

The most notable scholar on The Classic of Tea in modern Japan was Morooka Tamotsu. His representative research outcomes include A Biography of Lu Yu: The Sage of Tea, Lu Yu and The Classic of Tea, Comments and Explanations of The Classic of Tea, and Additions to Comments and Explanations of The Classic of Tea.

Nunome Chofu is one of the representative contemporary Japanese researchers in the field. He collated The Classic of Tea in detail and published eight versions of the book in his Complete Chinese Tea Works, including a few rare copies of the classic.

In Korea, the propagation of The Classic of Tea started in recent decades. Choi Beom-sul’s The Korean Way of Tea (Hangukui Chado) incorporates several chapters of the masterwork. Later Kim Un-hak translated the whole book into Korean and placed the Zheng Si edition at the beginning of the appendix to his Korean Tea Culture, which enhanced Korean people’s understanding of the history of Chinese tea culture.

The westward spread of tea leaves via land routes has had a long history. In the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), silk and tea leaves were valuables carried west through the Silk Road. In the Tang Dynasty, tea drinking was trendy in the Central Plains. Arabs from West Asia, who came to China for trade purposes, were important carriers for the westward transmission of Chinese tea culture. While buying great quantities of silk and porcelain, they also took tea leaves back to their homeland. Tea customs hence caught on in some regions of West Asia rapidly. The wave swept not only Northern and Western Europe, but even as far as Africa.

The Classic of Tea was imported to Europe later. Not until after the 17th century did it have an impact. Successively it was translated into Western languages, such as English, German, French and Italian.

Italy was among the first countries in Europe to study Chinese tea. In 1559, three important works of renowned Venetian writer Giovanni Battista Ramusio were published, namely Notes on Tea, Notes on Chinese Tea and Travel Notes, which also record The Classic of Tea.

Contemporary Venetian scholar Marco Ceresa published the Italian translation of the tea classic in 1991, which is the most complete translation in the West so far. The first edition was sold out soon after it came onto the market, reflecting European society’s strong interest in The Classic of Tea.

From material to cultural

The aims for translating The Classic of Tea varied in different historical stages, from simply transmitting material information concerning tea ware, tea leaves and tea making to spreading traditional Chinese culture.

In 1935, American writer William Ukers compiled and published the book All About Tea. “It remained for Lu Yu, a Chinese scholar, to compile, about 780 CE, the Cha Ching, the first book to be devoted in its entirety to tea,” Ukers stated at the beginning of his tea monograph. “To Lu Yu, the early Chinese agriculturists were heavily indebted. And if their debt was heavy, how much more so is the debt which all the world owes,” he added. Much content of Ukers’s book came directly from the tea classic, and the full text was included.

Due to his limited knowledge of Chinese culture, Ukers simply introduced the main idea of each chapter of Lu Yu’s magnum opus and didn’t elaborate on related historical origins and cultural connotations, so he failed to convey the essence of The Classic of Tea.

On the other hand, a series of articles written by American author James Norwood Pratt in the early 21st century not only became crucial to informing English speakers of The Classic of Tea in the contemporary age, but also lifted the translation of documents concerning Chinese tea culture to a higher intellectual level.

At the same time, English translations of The Classic of Tea by domestic scholars also paid high attention to translating Chinese cultural symbols, retaining the essence of the original to the greatest extent to deepen non-Chinese speakers’ understanding of Chinese culture.

The focus of debates over strategies to translate documents concerning Chinese tea culture also shifted toward a consciousness of equal cultural dialogue. The purpose of translating tea documents has been regarded as to engage in equal cultural exchange and to better spread traditional Chinese culture.

However, most extant referentially valuable books and records about tea culture are aged. Some information is outdated and impractical in developed society. Thus when translating tea culture documents, including The Classic of Tea, Chinese and foreign translators alike have depended largely on foreignization and occasional domestication in their translation methodologies, in a bid to disseminate tea culture more efficiently.

Cultural blending

The Classic of Tea and Chinese tea culture have been influential overseas not only because they intensified other countries’ interest in studying Chinese tea and were fused into their daily customs, but also because they profoundly impacted the literature, art and aesthetic communities of other nations.

After the introduction of The Classic of Tea to the West, a great number of tea culture monographs that were modeled after the Chinese classic emerged, and many countries tailored the tea ceremony to their cultural conventions. The tailoring attempts are interesting instances of integration in cross-cultural communication that reflect how other countries see Chinese culture.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, for example, British and French people preferred to use Chinese pottery as tea ware, and using tin pots, iron kettles or stainless-steel tea kettles was viewed as poor taste. The ambience echoed the “China craze” in Britain at that time. As China was seen as an ideal country in European culture then, the Chinese way of tea, as a token for elegance, was blended into the gentlemanly spirit in Europe.

The extensive translation, spread and research of The Classic of Tea promoted the shaping of the overseas clout of Chinese tea culture. Chinese tea appeared in many foreign literary and artistic works, mirroring the degrees to which countries around the world accepted traditional Chinese culture in different times.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, with the prevalence of tea drinking in the British court and society, many tea-related poems sprung up, which were dubbed “tea poems.” Many romantic poets from the 19th century lauded Chinese tea in their works, such as Percy Shelley, George Byron, John Keats and Samuel Coleridge. Moreover, Irish portrait-painter Nathaniel Hone drew a charming picture of a tea drinker in 1771, and English painter Edward Edwards created the work Tea at the Pantheon, showcasing that tea drinking was in vogue during the period.

Yuan Mengyao and Dong Xiaobo are from the School of Foreign Languages and Cultures at Nanjing Normal University.

edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE