13th and 14th C. texts illustrate global exchange on Silk Road and Grand Canal

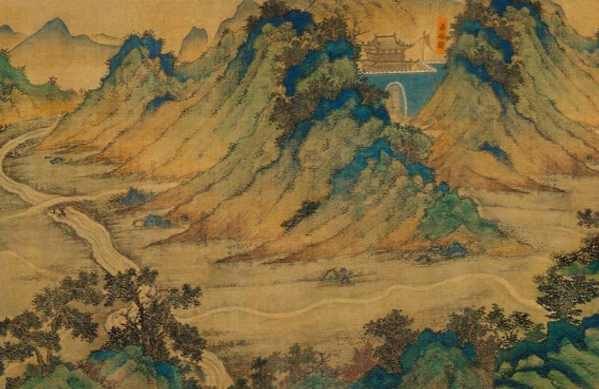

This detail (Above) of the Ming painting, “Landscape Map of the Silk Road,” depicts trade routes starting at Jiayuguan, the western end of the Great Wall during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Photo: FILE

The 13th and 14th centuries are considered a high point of world cultural integration before modernization. It is also a time when China was open to the world and beginning to play a leading role in global development. During this period, two great routes were crucial to China’s influence by facilitating trade and other relations within China and with the rest of the world. The Silk Road onland was a network of roads leading from China to Europe, Persia and India, while the Grand Canal, which served as the quickest route from north to south within China, connected the Silk Road onland with the Maritime Silk Road that extended eastward to Southeast Asia. The ancient route and canal linked China with the West, carrying goods and ideas between great civilizations and bringing about a golden age of cosmopolitan culture in China. The literary works between the 13th and 14th centuries provide a fresh perspective for analyzing and observing this golden age.

Geography

The Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) changed the former system of the Grand Canal to a direct north-south waterway from Hebei Province to Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province in southern China, extending southward to the East China Sea by the Zhedong Canal. The Yuan adopted the Song administrative structure and equipped each of the seven seaports (Quanzhou, Guangzhou, Qingyuan, Shanghai, Ganpu, Wenzhou and Hangzhou) with a Shibo Si (Bureau of Sea Trade) to manage foreign trade. These seaports were located on the Grand Canal or connected with it by waterways, thus creating a large network of inland water transport and maritime transport. For foreign travelers and merchants entering China via the Silk Road, the Grand Canal was the main option. The Yuan scholar Fang Hui (1227–1305) depicted in one of his texts the bustle of an yi zhan (a relay station for post horses in ancient China) in Suzhou, a metropolis of industry and commerce located on the Grand Canal. He said that people bearing tributes from countries around the South China Sea, envoys sent by Chinese emperors, and travellers from Northeast Asia and the West, all rested in the yi zhan. At that time, travellers and merchants from Japan and Goryeo (ancient name of Korea) sailed to China’s southeast coast and then went northward by the Grand Canal.

A Japanese Wu-Shan zen monk once traveled from Ningbo to Hangzhou via the Zhedong Canal. He was particularly impressed by the large number of ships berthed at the ferry station when he arrived at Hangzhou. In his poem, he depicted the station buzzing with different dialects and sails billowing with the breeze they caught. Westerners to China by sea usually landed at the ports of Quanzhou or Guangzhou, then headed to Dadu (the capital of the Yuan Dynasty, now modern Beijing) through the Grand Canal. A Muslim Moroccan explorer named Ibn Battuta (c. 1304–1368) gave a vivid account in his journal. When he arrived at Zaitun (Muslims referred to Quanzhou as “Zaitun,” meaning olive) in Fujian Province, he depicted hundreds of large ships and countless boats lying in the harbor, which was a large harbor extending inland to a river. He mentioned that he travelled south along the river for 27 days before reaching Guangzhou, where the river flew into the sea. From Guangzhou he went north to Hangzhou and then proceeded to Dadu through the Grand Canal. Ibn Battuta believed that all the waterways in China were connected together by a main canal. It appears that the Grand Canal meant a lot in Westerners’ appraisal of China.

In addition to ports, numerous yi zhan along waterways also helped keep the Silk Road unblocked, as they supported trips to the West and boosted many cities along the canal. The Italian explorer Marco Polo set out north from the Persian port of Hormuz, climbed over the Iranian plateau and the Pamirs, rode along the western edge of the Taklimakan Desert, through series of yi zhan and finally arrived at Dadu. Then he sailed south via the Grand Canal to Quanzhou and returned to his homeland by sea. There were more than 50 yi zhan along the canal. In an yi zhan, according to Fang Hui’s record, boats berthed at the quay in order; The yi zhan provided many services from food and drink to accommodation and entertainment.Travellers swarmed around, tired, while still happy to enjoy these services. This happiness was secured with an efficient policing system along the route. In his journal, Ibn Battuta praised China as the safest country for travelers. He wrote that even a single traveler with many belongings didn’t worry about a nine-month journey within China. He noted that in every yi zhan, the government officials registered all the travelers’ names and sealed relevant documents, which were then handed down to the next yi zhan for closer checks.

Scenes along the routes

Through the Silk Road and the Grand Canal, many special western goods appeared in common households in ancient China. Marco Polo wrote in his journal that “the quantity of pepper introduced daily for consumption into the city of Kinsay (today’s Hangzhou) amounted to 43 loads, each load being equal to 223 lbs.” He also mentioned that there were warehouses along the riverbank for merchants from India and other countries to store their goods. Traces of foreign specialties introduced into China can be found in many ancient texts. According to them, people in Jinling (today’s Nanjing, Jiangsu Province) were able to eat fresh fruits from the West. Exotic treasures such as xun lu (a kind of spice produced in Greece), pepper, fur seals, pearls, ivory and some other marine mammals, were shipped to the national capital through the canal. Adequate supplies made them affordable.According to a collection of anecdotes of the Yuan Dynasty, so many curious people came to watch a Westerners’ wedding in Hangzhou, which was “quite different from Chinese wedding traditions,” that the crowd stampeded and many were crushed or trampled underfoot. Chinese craftwork was carried to the West through the Silk Road. Ibn Battuta mentioned that there was a kind of container made of bamboo, which was unbreakable and could be used for hot meals. These containers were sold to India, Khorasan (a historical region in the northeast of Greater Persia) and other countries. In fact, this container referred to the famous Bamboo lacquerware produced in China.

While the booming trade exhibited exotic items in China’s local markets, scenes along the Grand Canal also reminded foreign travelers of their hometown. Ibn Battuta wrote that there were cottages, farmland, gardens and markets along the canal, and the population there was denser than that of the Nile valley. He also mentioned that before coming to China, he thought that the pears growing in Damascus were the best of all, but he changed his mind after tasting Chinese pears. When a European traveller named Giovanni dei Marignolli (1338–1353) travelled south along the canal from Dadu to Quanzhou, he wrote that there were a large number of cities along the river, rich in natural resources, especially some fruits that had never been heard of before.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, both the ancient Silk Road and the Grand Canal served as a corridor for trade and cultural exchange between China and other countries, constantly shaping the lives and thoughts of people along the route. In this way, China gradually became a country of the world.

Ren Tianxiao is from the Center of Jiangnan Culture Studies at Zhejiang Normal University.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE