Sociologists should engage more in the literary world

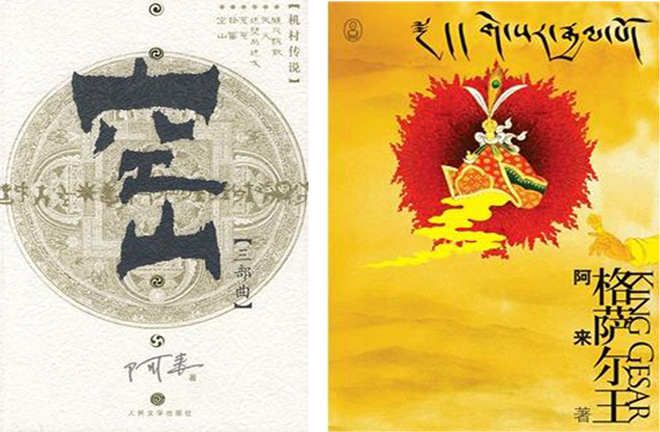

Pictured above are four novels written by contemporary writer of Rgyalrong Tibetan descendent Alai, namely Empty Mountains (Top Left), King Gesar (Top Right), Zhandui (Bottom Left), and Dust Settled Down (Bottom Right). Chinese sociologist Zheng Shaoxiong’s analysis of the four works was based on long-term and solid investigations into Tibetan areas and interviews with the author Alai, trying to represent the formation and evolution of the Kham Tibetan society from temporal and spatial dimensions. Photo: FILE

Sociology of literature is not a new discipline in China, but it has received little attention. It is mostly literary scholars doing research in the field; sociologists are few and far between.

Awkward situation

Literary works involve external and internal relations, and they feature textual forms, social structures and the wisdom of the author. Yet in the literary world, there is a strict exclusion of external relations and social structures, probably because of the fear that “vulgar” sociology will harm literature’s internal relations and features except for social structures.

The root cause for literature’s rejection of sociology lies in the worry about its own autonomy. Literary scholars fear that sociology will be like a bull in a china shop. Many of them therefore try to safeguard the autonomy of literature by highlighting the confrontation between literature and science, between personality and sociality, between peculiarity and structurality, and between individual sensitivity and universal rationality. This usually manifests in the disorientation of scholars when they face the conflict between Theodor Adorno’s social criticism theory and Alphons Silbermann’s empirical sociology of literature, such that it is difficult to define and categorize sociology of literature as a discipline.

The trend of integrating sociology while at the same time freeing literature from its imagined harm has fettered the development of sociology of literature. Most of the rare pertinent papers in China focus on what sociology of literature is and how to build the discipline as a branch, making it formalistic without research practices.

Compared with the liveliness of the literary world, sociologists seem to regard literary works as a pastime or as bedtime reading materials. Few of them have taken literature seriously, particularly in the Chinese sociological community. For one thing, literary writers consider works as vehicles to pour out their emotions and values while sociologists adhere to value neutrality, and for another, sociologists are reluctant to indulge themselves in literature. They are more willing to devote their energy to gargantuan field studies, questionnaire design and data analysis to realize their ambitions of benefiting the people. Due to their rejection of literature in favor of science, sociologists’ imagination can wither away.

Intrinsic compatibility

As literature rejects sociology for the sake of autonomy, individuality and sensibility, and sociology rejects the fictiveness of literature in the name of science, the two communities have neglected three fundamentals.

First, there is no absolute autonomy and individuality. All works are inseparable from specific customs and social structures, including literature. Second, sociology tends to show empathy methodologically and ontologically. Qu Jingdong, a professor of sociology at Peking University, noticed that sometimes sociologists will attend to a single scenario, consider details one by one, and try to understand others’ emotions in individual stories just as humanities scholars do. Thus, science and art, literature and sociology, sensitivity and rationality, fiction and science, autonomy and society, individuality and structure are not in complete opposition. Moreover, fiction does not only exist inside society; it is also a vehicle for sensitive writers to understand and represent folk customs and the structures of the society they are in and to conceive an ideal society.

Academic writings in the literary form are not unusual. Since sociology was introduced to China, typical examples include the classic The Golden Wing: A Sociological Study of Chinese Family authored by renowned sociologist Lin Yaohua and the recent Stories of Petitioning Migrants from Dahe Hydropower Station written by Ying Xing, a professor of sociology from China University of Political Science and Law.

Especially after the postmodern turn, field research works are no longer regarded as value-neutral reflectionist theories, but as writings instead, further blurring the boundary between sociology and literature.

When talking about the value of sociology to literature, Pierre Bourdien pointed out that expressions of literature and science are barely different in essence. Both attempt to represent the most profound structures, including the mental apparatus, of the social world. The only different aspect is that literature aims to make the structure invisible to readers, while science tries to tell the truth of an object explicitly and requires to be taken seriously. Hence sociology enters the literary world in order to revitalize the authors and the environment they are in, thus reconstructing a social reality.

Specific to sociological techniques in literature, or art by extension, Bourdien shed light on how to carry out sociological analysis on the art of painting in Italy in the 15th century. He noted that rebuilding the moral and mental world of Italians at that time, namely social conditions, is vital to understanding the style, demand and market of painting then. The sociological requirement can be perceived as the general rule of sociology of literature, whether in China or other countries.

In 1927, Chinese writer Lu Xun delivered a speech titled “Wei-Jin Demeanor and Essay’s Relationship with Medicine and Alcohol,” which is a true model of sociology of literature in Bourdien’s sense. He not only analyzed how individual writing and life styles influenced the style of writing of the times and later generations; more importantly, he drew a very sociological conclusion: there were no completely pastoral or secluded poets even in ancient times, as their poems unavoidably revealed the authors’ attention to political or worldly affairs.

Lu Xun’s discussion is clear and concise. If we examine the literary field of the Wei and Jin dynasties using the framework Bourdien employed to analyze Gustave Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, we can achieve detailed and systematic results like those in the thinking of Lu Xun. The coincidence of thought between Bourdien and Lu Xun beyond time and space reflects the intrinsic compatibility between literature and sociology.

Importance of approaching literature

In the debate between Adorno and Silbermann, two research paths for sociology of literature are apparent. Cultural criticism integrates Marxism and Kant’s aesthetics. Exposing and criticizing phenomena of cultural alienation, cultural criticism has been inherited by many literary critiques of later generations. Empirical sociology of literature, on the other hand, does summary and statistics of various social conditions on the premise of adhereing to reality.

French sociologist of literature Robert Escarpit accepted the second path. He clarified the general rules of literary production, publication and consumption through quantitative approaches. Although the empirical path doesn’t get inside specific literary works, it is equally effective in deconstructing the independence of literature. Moreover, its methodology and conclusions are not unique to literature, but applicable to other research objects and areas. However, the overemphasis on the external environment of literature might lead researchers to overlook the wild imagination and profound societal constructions of each work and author.

This is why sociology should approach literature exactly as Bourdien advocated. His analysis of Flaubert’s Sentimental Education exemplifies the importance of taking literature as a point of departure in sociological study. He associated with the social context of the author to analyze characters and content in the work, thereby perceiving the self-reflection of the author. Then he placed the thinking in the broader literary field to look into the destiny and future of intellectuals including Flaubert.

Sociologists of literature might not wholly accept Bourdien’s consciousness of problems, but his approach of connecting and interpreting external and internal worlds should serve as an essential weapon for scholars entering from sociology into literature.

In recent years, a handful of papers on sociology of literature emerging in the Chinese sociological community have followed this path consciously or unconsciously. Zheng Shaoxiong, an associate research fellow from the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, systematically analyzed four novels composed by contemporary writer of Rgyalrong Tibetan descendent Alai, namely Empty Mountains, King Gesar, Zhandui, and Dust Settled Down. His analysis was based on long-term and solid investigations into Tibetan areas and interviews with Alai, trying to represent the formation and evolution of the Kham Tibetan society from temporal and spatial dimensions.

Xiao Ying, a professor of sociology from Shanghai University, interpreted famed writer Han Shaogong’s A Dictionary of Maqiao on the basis of his own life experiences in the rural society of Hunan Province. The alignment of the scenes in his childhood and teenage periods with Maqiao prompted Xiao to take the work as a field text of anthropology and seek the mechanisms that make up the daily order of the quasi-natural society from seemingly scattered and disordered entries.

Yang Lu from the School of Sociology at China University of Political Science and Law incorporated Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in the vein of social theory to explore how Defoe looked for a path of self-discipline in an era when Christian traditions failed to comfort the public.

For sociology, approaching literature is like approaching history. It is not to embrace another sub-discipline or object for analysis, but to awaken sociologists to reflect on themselves and walk out of the hedges of the sociology-centered mentality. It is to expose them to literature’s emotional engagement in and writing of real life and recover their plain feelings veiled by abstract empiricism, so they can not only discover problems from emotional communication, but also feel the pulse of human life and social operation using the complementary nature of rational and emotional intelligence.

Xiao Ying is a professor from the School of Sociology and Political Science at Shanghai University.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE