Monarchy and powerful clans reshaped Han Dynasty state and social order

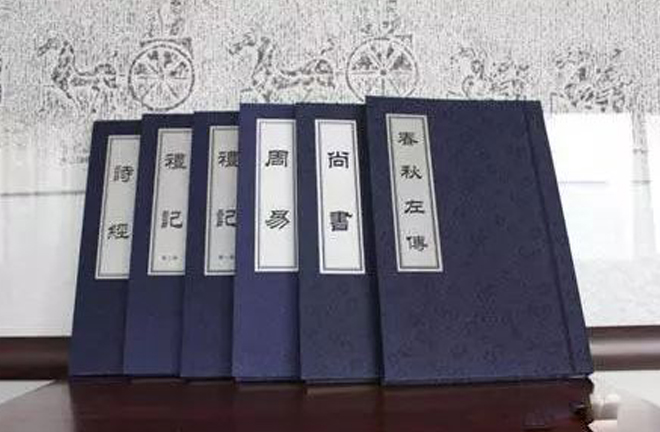

Powerful clans in the Han Dynasty took the Six Classics, namely The Book of Songs, The Book of History, The Book of Changes, The Book of Rites, The Book of Music and The Spring and Autumn Annals, as codes of thought and conduct. Photo: FILE

Among the various social strata and groups in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), the powerful clans best reflected the interaction between state and society. The group had dual attributes. For one, scholar-officials in the clans constituted part of the state power system; and for another, they were leaders in local society with the backing of clansmen. They represented both the state and society, forming the social foundation of state power.

In the Western and Eastern Han dynasties, powerful clans interacted with the state and evolved under the control of the monarchy. However, they were not completely passive when accepting the control; rather, they responded in different ways and reconfigured the societal structure.

Absolute dominion of monarchy

“Rule by power was an important feature of ancient Chinese society,” said late historian Liu Zehua, “so the accumulation of power would normally affect all sectors of society.” In state-society relations in ancient times, the monarchy was the embodiment of state power. The political power it represented was dominant.

Under the hereditary monarchy, state-society relations could be interpreted as those between monarchy and society, so state control was essentially the dominion of monarchy over society.

In the early Han times, the relative separation between state and society was the fundamental reason for state control and social integration. There were numerous social forces at that time, including the imperial clans of six kingdoms, noble descendants, men of immense wealth, vassals, and landlords with military merit.

Relying on political, economic and clan strengths, the social forces formed their respective social orders, breaking away from the unitary monarchical control and even confronting the state, which largely threatened and undermined the unitary order built by the monarchy. To quote The Book of Han, “Civilians would dare to contend for power with the emperor in case of weak state power.” This line reveals the relationship between the monarchy-centered state and society.

Under the unified dominion of the monarchy, social order must highly align with state order. Any social forces that transcended state order were suppressed until they succumbed or submitted themselves to imperial rule. That was how the Han states exercised control over society and integrated it.

From the evolutionary course of the Qin and Han dynasties, the monarchy governed society mainly through power manipulation, institutional integration and ideological control. First, the state led social forces by means of power regulation, controlling the whole society through the power system. In monarchy-dominated society, power not only played a decisive role in the occupation and allocation of diverse social resources and interests, but also guided the transformation of social classes and strata.

When it came to powerful clans, they represented power, real estate and culture, but first of all, they grasped for power while bowing to the monarchy. With power, they could expand family clout. This is an inherent law in traditional Chinese society.

Institutionally, the state set sound and rigorous rules and control systems that embodied the will of the monarchy. Systems were reflections of state will and means by which the state maintained the order of power.

The Han states controlled, guided and integrated society through a series of systems. As manifestations of the institutional design, the central authority steered local governments, and the state fettered individuals of targeted social strata and restricted their access to benefits.

Societal control and integration were intimately related to state ideology. The latter determined the basic content and way of the former. In the Han Dynasty, Confucianism was the philosophy for state governance, stressing the superiority and central role of the monarch to realize ideological integration and to control social strata and forces.

Han thinkers and politicians emphasized that the emperor was the foundation of the country. Whether in theory or practice, they advocated the supremacy of the monarch.

All in all, the Han states tried every means to control and guide social forces. During the reign of Emperor Wu, the central authority exercised total control over society and integrated it through power, institution and ideology. After the mid-Western Han era, various social forces gradually transformed into powerful clans including bureaucrats, landlords and scholars, a process representing the incorporation of social forces into state order.

By joining the state power system, powerful clans built direct connections with the monarchy and turned from targets of oppression into the social foundation of state power.

Under the monarchy, society was generally controlled by the state. In other words, social strata and forces lacked independence and autonomy, subject to the manipulation of the state. As society was an appendage to the state, social order highly complied with state order, bringing into being a unitary state-society structure with the monarchy at the core.

Clout of powerful clans

In the Han Dynasty, the state controlled all sectors and forces of society. There was no binary opposition between the two. However, the state was grounded in society and couldn’t function without it. Social strata and forces didn’t accept state control completely passively. Instead, they responded differently in different periods and conditions.

Generally, society responded to state control in two ways. First, it echoed the state, following the monarchy to contribute to the unitary state-society structure and maintain the balance between state and social order. Second, social forces checked the state using different means to safeguard their own interests. The state couldn’t afford to ignore social forces, so it constantly adjusted its methods of control. By interacting with the state, social strata reshaped and reconstructed the state and society.

First, state power was exercised through bureaucracy at all levels. Social forces joined the state power system and influenced the functioning mode and dominant role of state power, thereby impacting the development of state-society relations. As powerful clans in the Han Dynasty successively entered the state power system, they owned both political power and social authority, serving as the bond linking the state and society and making the relationship cooperative, rather than antagonistic.

Under the major premise of state power controlling society, powerful clans interacted with the state by grabbing power, influencing state control and policy implementation to varying degrees. As a result, the state would change its way of control, adjust ruling policies, and even make compromises in some spheres.

Having local authority, powerful clans controlled primary-level society through power occupation, social networks and their prestige, thus reshaping it. Occupying powerful positions and monopolizing power were fundamental to their social networks. Extending and strengthening social relations, they built social networks in which clansmen, relatives as a result of marriage, subordinates, teachers, friends and fellow villagers were interwoven, shaping a unique order in village-based society.

Meanwhile, as they gradually observed Confucian doctrines and became gentry, they attached more importance to ethics and the prestige in village control. Prestige, in particular, was what attracted powerful clans to control village communities.

In the late Western Han society, the village community with elders at the core arose, as did a community of powerful clans. Gradually, powerful clans occupied the positions of influential elders and declared themselves as agents of the monarchy keeping village order.

Therefore, the control of the Han states over the village-based society was manifested in the reconstruction of primary-level society by powerful clans in a certain social structure.

Moreover, the Confucian and gentry orientation of the group promoted social integration in the era, rebuilding social ideology and the intellectual world of the clans. Accepting Confucian ideas and ethical norms, they took the Six Classics, namely The Book of Songs, The Book of History, The Book of Changes, The Book of Rites, The Book of Music and The Spring and Autumn Annals that were recognized by the monarchy, as codes of thought and conduct.

Under the influence of Confucianism, their intellectual world shifted from military to civil. At the same time, the Six Classics and Confucian ethics constituted the core of their clan culture and the basic content of their family education and tradition, thus reconstructing social cultural traditions.

Scholar-officials in the clans also resorted to Confucianism and moral power to condition and criticize behaviors of the state or the monarch, which was a form of state-society interaction. There were abundant instances in history in which scholar-officials from powerful clans insisted on ethical traditions to restrict the monarchy, but it was simply a regulation, and by no means a fundamental counterbalance against it.

A concrete analysis of the interaction between the state and powerful clans can offer us a glimpse into the absolute rule of the monarchy in ancient states and how social strata reshaped and reconstructed the state and society. This will also help us examine state-society relations in the contemporary world through historical and global lenses.

Cui Xiangdong is a professor from the College of History and Culture at Bohai University in Liaoning Province.

edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE