Chinese mythology mirrors nation’s unrelenting spirit

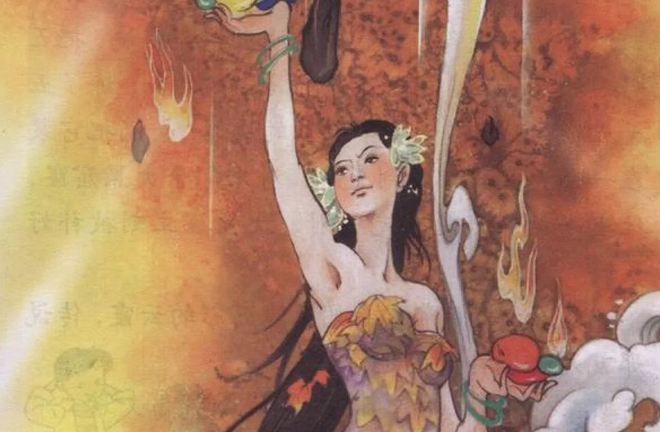

Nüwa patching up the sky Photo: FILE

Chinese President Xi Jinping has stressed the significance of Chinese mythology many times. Particularly at the closing meeting of the first session of the 13th National People’s Congress in March this year, he cited ancient myths, such as Pangu creating the world, Nüwa patching up the sky, Fuxi drawing eight diagrams, Shennong tasting herbs, Kuafu chasing the sun, Jingwei filling up the sea and Yugong removing mountains, to illustrate that Chinese people have always held fast to their dreams and made endless efforts to realize them over a history of thousands of years.

The Chinese nation has created and accumulated colorful myths in the long course of history. Many myths not only reflect the excellent cultural traditions of each ethnic group, but have influenced people’s values and spiritual beliefs profoundly as well. Their themes, especially those of creation myths, have become the inner power inspiring the Chinese people to create and innovate.

Collective dream chasing

Chinese mythology embodies a spirit of collective dream chasing. Myths are cultural narratives formed out of the imagination and creation of the people. In other words, they are “dreams” people have woven out of their own survival and development, mirroring a collective pursuit. That is why many scholars have argued that myths are holy narratives that human beings use for self-regulation.

According to the developmental law of humanity, when basic necessities of life are met, people will have higher pursuits and goals spiritually. We call them “ideals,” or “dreams,” figuratively speaking.

“Dreams” in mythology are not individual ideas in the general sense. They are collective thought. Especially in ancient times, myths were, to a great extent, important carriers for humans to construct their beliefs. Moreover, a myth is not generated or inherited by an individual. Mythology is a reflection of group consciousness.

Take the myth of Kuafu chasing the sun as an example. On the surface, it is an individual act, chasing the sun for a certain purpose. However, in the subtext developed through the interaction between different storytellers and audiences, Kuafu is a symbol for the unremitting quest for a goal. Kuafu represents not only a group of mighty giants, but the positive attitude of early humans towards the world. Although he died of thirst and exhaustion, his positive, enterprising spirit has been carried forward. In the myth, his ending is moving, but not tragic. Following his death, the wooden club he had been carrying grows into a vast forest of peach trees called Denglin Forest. Just as Pangu turns into all things on Earth, Kuafu transforms into new lives, symbolizing the continuation of his spirit.

In the fable of Yugong removing the mountains, the protagonist, who is derided as a foolish old man, contends that while he may not finish this task in his lifetime, through the hard work of himself, his children, and their children, and so on through many generations, someday the mountains will be removed. Kuafu’s story is in the same vein. Many myths were in essence created to deliver “positive energy.” They aim to inspire later generations never to give up if there is hope.

Therefore, simple as they are, myths have been remembered and passed down from generation to generation. Despite changes in the mode of production and living environment, they are like hereditary treasures. One of the fundamental reasons for their worth is that myths provide a value system on which humans can base themselves and aspire.

Carrier of culture, wisdom

Chinese mythology carries cultural traditions and the wisdom of survival. Mythology is undoubtedly the earliest form of inherited culture. Myths were created in oral languages, rather than in written forms. Compared with oracle bone inscriptions of 3,000 years ago, language has a much longer history.

Mythologists generally maintain that myths emerged in the late Neolithic Age about 10,000 years ago. With time, many written documents have been forgotten, but myths passed on by word of mouth remain widespread till now and endure. Why?

For one thing, mythology brought into being a great cultural tradition involving oral accounts, historical relics, customs and literature. It can be found in almost all spaces and times of human production and life. Collectively recognized values, outlooks on life and world views, as well as cultural fields like literature, history, philosophy and law, can all be traced back to ancient myths.

Mythology is rich in content and various in type. Distinct from other cultural forms, it is the earliest cultural memory in human history, and it contains thousands of years of human production experience. It is regarded sacred not because it involves gods. The portrayal of gods is to indicate historical experience and the value judgment of the human race.

An in-depth examination of some myths would reveal great disparities from the common narrative. For example, Nüwa is associated with two myths, creating mankind and patching up the sky. When analyzing Nüwa creating mankind, scholars from different academic backgrounds might uncover relations between gender concepts and social forms. Perspectives from philosophy, cultural anthropology and sociology can all tackle the historical root cause for why mythology is always included in holy textbooks. The story of patching up the sky, on the other hand, doesn’t simply create a heroine, but a worthy cultural ancestor of the Chinese nation who could bless later generations.

Chinese mythology also showcases Chinese characteristics and cultural confidence. It is a cultural tradition with a basic, profound and lasting power in the development of a nation and an ethnic group. Most Chinese myths, in particular creation myths, reflect the cultural consensus of the Chinese nation, such as the myths of Pangu, of Nüwa and Fuxi and of Emperors Yan, Huang, Yao, Shun and Yu widespread in many ethnic groups.

From the inheritance and acceptance of these myths, we can see the confidence of the Chinese nation in its culture. Different from Western mythology that believes God created the world, Chinese myths serve to build the image of cultural ancestors unique to the nation. They stemmed from people’s self-reflection. Whether speaking of Pangu separating Heaven from Earth or of Fuxi and Nüwa getting married as brother and sister and giving birth to human beings, they are down-to-earth creators, incarnating numerous cultural ancestors and heroes. They are divine creators enriched and developed by the Chinese based on their own culture.

Ethnic harmony

We can also find social responsibility in Chinese mythology. For example, those stories conveying ethnic harmony are not only a highlight of Chinese mythology, traditional culture and the nation, but also representatives of an indestructible dream cherished by all ethnicities.

In the myths of the Han and other ethnicities, many ethnic groups are interpreted as brothers and sisters, which is a distinctive Chinese characteristic. For example, according to myths of the Achang ethnic group, the Han, Dai, Jingpo, Lisu, Achang, De’ang and other ethnicities were born out of a big gourd. Those of the Blang ethnicity tell that brothers from Heaven descended to the world and became the Han, Wa, Blang, Lahu, Dai and other ethnic groups. Tibetan mythology makes it clear that the Han, Tibetan and Lhoba ethnic groups are brothers.

The narrative of many myths that brother and sister got married and gave birth to ancestors of the ethnic groups is a selective expression of the relations among ancient ethnicities, reflecting a positive cultural faith. The faith supports the contemporary cultural confidence in ethnic harmony and suggests the objective history of China as a unified, multi-ethnic country. Myths of this kind are certainly the cultural power encouraging all ethnic groups to work together.

Myths not only carry the excellent cultural tradition of the Chinese nation, but also highly align with core socialist values upheld in the new era, integrating an enterprising attitude, national spirit and devotion to family and country.

Innovation and creation, dedication, cultural order and survival rules advocated in mythology give full expression to the great dream of building a prosperous, democratic, civilized and harmonious Chinese nation that all ethnic groups have cherished for so long.

Chasing dreams is the lifeblood of the Chinese culture and nation. A series of mythological images like Pangu, Nüwa, Fuxi, Shennong, Kuafu, Jingwei and Yugong have inspired generation after generation to dream and fight for the benefit of mankind. The dream will definitely exert positive, far-reaching impacts on the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation in the new era.

Wang Xianzhao is a research fellow from the Institute of Ethnic Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

(edited by YANG XUE)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE