Historical contest over sea turns nature into politics

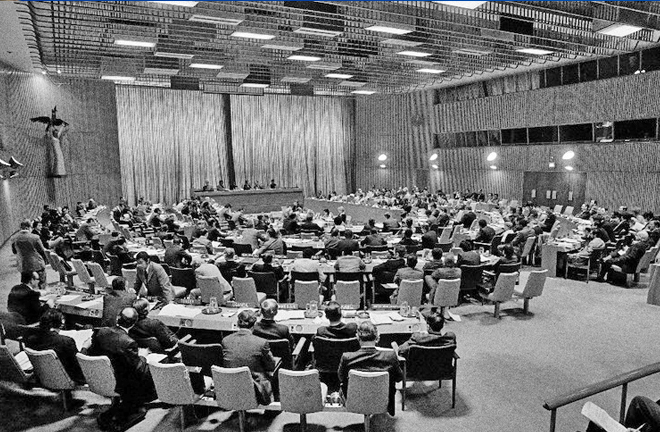

The third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea kicked off in New York in 1973, marking the beginning of the fourth stage of sea partitioning in human history. Photo: FILE

Long ago, the old sea was boundless, bottomless, legendary and mysterious to young mankind. Through exploration, discourse and contention in modern years, humans have not only unveiled the truth about the sea, but also fundamentally changed its character.

From natural to political

Deepening knowledge of the sea has to some extent bore on the development of human society. The sea is a colossal body of water covering 71 percent of the Earth’s surface. Liquid, connected and open, it doesn’t have salient features like distinct landforms. Moreover, it is subject to the combined pressures of sea winds, waves, currents, and water mass all year round. Thus the sea is a vast, profound, mysterious and changeable natural existence.

At the end of the 15th century, however, not only was the seaway to the East Indies found, but the voyages undertaken by Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan led to the discovery that the sea is connected and safe to cross.

Great geographical discoveries woke humans up to the huge role major world navigation would play in advancing social development, and these discoveries made whole their understanding of the sea. Via the ocean, humans can reach every continent and island of the Earth. This was the turning point for how the land and the sea were recognized.

The attribute of the sea was redefined at that historical moment, when it was no longer regarded as a moat dividing the land. Instead, it became a medium linking the land and the world. As the global panorama unfolded to mankind, the sea gained unprecedented value. Humans just couldn’t wait to carve it up.

The opening of the sea route to India and the discovery of the New World made Portugal and Spain into global sea empires engaged in furious competition for their respective maritime interests. From then onwards, brutal fights were staged on the vast waters one after another. The sea bore witness to the rise and fall of regional and global oceanic powers.

It can be seen that the political attribute of the sea stemmed from those great geographical discoveries and grew increasingly complicated. In the process, countries around the world built new connections with the sea.

Thereafter, it turned from an object of the Earth into an object of ownership, becoming an object coveted by countries around the world, from which derived the core issue in sea politics—who does the sea belong to?

Though as blue as usual, the global ocean is no longer calm. Its existence has transformed from natural to political. After the mid-15th century, when Portugal and Spain took the lead with geographical discoveries, Western powers like the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, Japan and the United States successively sought hegemony on the sea.

Resorting to maritime channels and motivated by colonial plunder, they started naval wars many times vying for resource-rich locations and strategic hubs. Amid the fierce contention for oceanic hegemony, the political character of the sea was strengthened constantly, and for nation-states the sea became a royal road to prosperity.

‘Blue enclosure movement’

Oceanic politics centers on “who the sea belongs to,” “who allocates the sea,” and “how to partition the sea.” These issues represent the political activities of sovereign states, such as conflict, coordination and cooperation for the sake of maritime interests. In total, humans partitioned the see in four stages, or “blue enclosure movements.” The participants and targets varied in each stage.

Portugal and Spain, pioneers of the Age of Discovery, were the first to carve up the global sea. By means of papal brief and related treaties, they divided the sea into two, occupying global oceanic trade and navigation rights in an exclusive fashion.

France and the United Kingdom came next. The United Kingdom, in particular, proposed dividing the sea into “territorial seas” within the sovereignty of the relevant coastal states and “high seas” on which all countries enjoyed the freedom of navigation. The division was soon widely accepted by the international community, except for the limit on the breadth of territorial waters at three nautical miles.

However, before WWII ended, US President Truman issued two proclamations successively on Sept. 28, 1945, to establish government control of natural resources in areas adjacent to the coastline.

Under the “guidance” of the United States, some Latin American countries released similar decrees one after another, advocating jurisdiction over 200 nautical miles. What followed was the signing of such treaties as the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, the Convention of the High Seas, the Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas and the Convention on the Continental Shelf.

Nevertheless, the pace of partition didn’t stop. The third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea convened for nine years from 1973 to 1982 and marked the beginning of the fourth stage of sea partitioning in human history. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a result from the conference, allocated 130 million square meters of the high seas to coastal states, accounting for 36 percent of the original total area of the high seas, namely, 360 million square meters.

The divided waters were those of highest value in exploitation and utilization. They held 94 percent of the total oceanic reserves of living resources and 87 percent of total oil reserves. In addition, they covered almost all traffic thoroughfares on the sea.

Hence coastal countries around the world tried their best to divide and occupy the global ocean to the greatest extent, with the scope and content they scrambled for extending continuously. The area of the high seas gradually shrank while the nuances of sea politics became enriched. From contention over navigation and fishing rights to controversies over coastal waters and breadth of territorial seas, from the establishment of contiguous and exclusive economic zones to overlaying waters, the continental shelf, and seafloor resources—obviously the scramble for sea interests will continue, along with the growing complexity of sea politics.

Discourse in sea politics vital

Playing a key role in sea politics, norms provide a source of legitimacy for maritime behaviors and certain oceanic laws and institutions. A review of the 500-year evolution of sea politics norms reveals that the building of the maritime order has featured ongoing tugs of war between freedom and control, openness and closedness, and sharing and monopolization.

Sea politics norms constitute not only a system of rules, but also a system of discourse. Political norms and discourse are intrinsically and essentially linked. During the construction of sea politics norms, political discourse always comes first. In other words, discourse guides the building of norms.

Since discourse provides just causes for countries to observe and obey sea politics norms, the former not only guides the latter, but also potentially restricts the latter’s development. Discourse is both a tool to exercise power and a key to seize power. Five-hundred years of sea politics practices show that whoever owns the discourse power over the sea can dominate the making of the global sea politics rules and the development of sea politics. So to speak, sea politics norms are expressed through discourse, and sea politics discourse reflects the operation mechanism of norms while conditioning and guiding their development.

At the juncture of history and reality, from Ming-Dynasty mariner Zheng He’s expeditionary voyages to escorts in the Gulf of Aden, the sea has been more than a natural existence; it has greater significance. China’s building of a strong sea power conforms to the country’s development and the tide of world development. It is also vital to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

Lin Jianhua is a professor from the School of Political Science and Administration at Liaoning Normal University, and Zou Guannan is a graduate student at the school.

(edited by CHEN MIRONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE