The moral connotations of pine and cypress trees

A painting by Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) depicts that scholars make tea under pine trees by a stream.

One of the three companions in winter, together with bamboo and plum trees, pine trees in Chinese culture are symbols of people who maintain moral integrity and principles in the face of calamity and difficult situations.

In his masterpiece Dragon-carving and the Literary Mind, Liu Xie (c.465-c.520) wrote “Human beings are born with seven emotions. They stir in response to the environment. It is natural that people express themselves when emotions stir.”

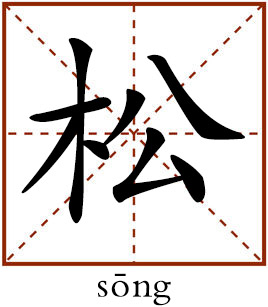

Various flowers, grasses and trees that have become associated with emotions about prosperity and death have long been used to enrich themes of Chinese literature. Resistant to low temperatures, songbai (pine and cypress trees) are natural symbols of certain virtues pursued by Chinese people. To some extent, pine and cypress trees have become symbols of the ideal personality admired in Chinese culture. Many works of literature across all recorded dynasties draw analogies between the attributes of these trees and human virtues.

Moral integrity

Unlike other plants that endure seasonal changes of color, songbai remain green throughout the year. As early as the pre-Qin period, songbai had already gained clear connotations as symbols of human personality.

The Analects recorded a famous comment by Confucius on pine and cypress trees: “Only when the year grows chilly do we see that the pine and cypress are the last to fade.” Taoist philosopher Chuang Tzu quoted this sentence and explained “An attitude of self-examination will eventually lead one to the Tao and enable one to preserve virtue in the face of danger. When a cold winter is coming and snow and frost are falling, I am afforded the opportunity to see the pines and cypresses still green and lush.”

Another Confucian philosopher, Xun Zi (c.313-238 BCE), also wrote that “Even when a gentleman is in dire straits and bitter poverty, he does not lose his way. Although he is tired and exhausted, he does not behave indecorously. In the face of calamity or great difficulties, he does not forget the smallest requirement of his belief. Not until winter comes, do we know the character of pine and cypress trees. Not until [a nation] has encountered difficulty, do we know the character of a virtuous person. There is not a day that passes when he is not there.” Songbai remain green in the face of chilly winter. This character was analogized to a person’s moral integrity in the face of calamity or difficulties. Pine and cypress trees then became a symbol of a person who remains virtuous during turbulent days.

Songbai are vigorous and the wood of these trees is solid. Chinese literati consider them to have a strong “heart,” symbolizing the strong heart of a virtuous person who never surrenders to the difficult situation and remains steadfast in his values.

The Book of Rites first proposed the idea that songbai have “heart.” It reads “They are to a person what their outer coating is to bamboo, and what the heart is to a pine or cypress. These two are the best of all the (plant) world. They endure through all the four seasons without altering a branch or changing a leaf. A virtuous person observes these rules of propriety, so that all those in his remote circle are harmonious with him, and those in his close circle have no dissatisfaction with him. People and things are affected by his goodness, and the spirits and gods also enjoy his virtue.”

The Confucians in the pre-Qin period admired pines and cypresses for they were the last to fade in a chilly winter and for having a “heart” symbolizing loyalty to one’s beliefs. Gradually, songbai ascend to cultural symbols representing an unyielding mind which remains as a faithful heart to one’s values in the face of calamity and difficulties.

Individual charms

In the Wei-Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties (220-589), songbai symbolism was preserved and further developed. In addition to symbolizing a virtuous person with moral integrity, more attention was paid to the unrestrained manner of a celebrated scholar, shifting its emphasis from personal morality to personal charm.

For example, A New Account of Tales of the World by Liu Yiqing recorded the manners of Ji Kang (c.224-c.263), a prominent writer and one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove in the Three Kingdoms Period.

Ji Kang’s body was seven chi (one meter equals three chi) and eight cun (one chi equals 10 cun) tall. His manner and appearance both stood out. Someone who saw him sighed, saying, “Serene and sedate, fresh and transparent, pure and exalted!” Others would say “Soughing like the wind beneath the pines, high and gently blowing.” Shan Tao (220-280) said “As a person, Ji Kang is majestically towering, like a solitary pine tree standing alone. But when he is drunk, he leans crazily like a jade mountain about to collapse.”

Those adjectives modifying the pines, such as “soughing wind” and “towering” also described the manner of Ji Kang. The word “soughing” described both the wind beneath the pines and the brisk and vigorous manner of Ji Kang. The word “towering” described the unyielding and proud manner of Ji Kang, who never compromised his beliefs even in face of isolation. As a son-in law of the royal family of Wei Dynasty, Ji Kang was killed when he refused to cooperate with the Sima family, who established the Jin Dynasty.

The changes in songbai symbolism in the Wei-Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties were closely related to the popular fashions at that time—the obsession with natural scenes and Xuanxue, an idealist philosophical sect that combined Taoist ideas with Confucian doctrines, on the basis of philosophies of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. The aesthetic awareness of the natural beauty of the scholars in this age advanced beyond their time. The evaluation of the character of a person was no long purely a judgment about one’s moral behavior. It paid more attention to the demeanor, tastes and brilliant expression of one’s emotions. The towering image of pines and cypresses symbolized the unrestrained manner as well as the independent temperament of the celebrated scholar of this period of time.

Aspiration, self-esteem

During the Tang Dynasty, songbai gained more cultural connotations as they became vehicles for literary scholars to express their aspirations and feelings. They became symbols of scholars who wished to serve the people while, at the same time, maintaining their self-esteem and individuality. These scholars were passionate and confident in pursuing worldly careers. However, they were also honest, frank and straightforward and refused to compromise on their principles. In the Tang Dynasty, songbai represented scholars who considered it their duty to make the world a better place. Meanwhile, the rich individual spiritual worlds and charming personalities were also described through literary works about pines and cypresses.

Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism fused in the Song Dynasty. Confucianism absorbed the Buddhist life philosophy of following the guide of karma and destiny as well as theories about minds. It also absorbed Taoist spirits about transcendence and self-realization. Influenced by this spirit of the time, the image of pine and cypress trees in the Song Dynasty carried the moral integrity admired by Confucians, the transcendent spirit of Buddhists and the freedom and unrestrained attitudes valued by Taoists.

Songbai carried the pursuit of a Confucian personality that had a strong resolution and broad minds. Planting a pine is seen as “fostering virtue.” In addition to its traditional symbolism of moral integrity, forever green pines were also seen as symbols of people who were indifferent to contending in fragrance and fascination with Kitsch flowers.

In contrast to the traditional saying that songbai have “hearts,” some scholars also proposed that songbai had neither “hearts” nor “emotions.” Without hearts or feelings, they would not be stirred by the outside world and this could maintain their authenticity.

Contrary to the common method of comparing pines and cypresses to useful people that would benefit society, some scholars admired the eccentric pines that could not be used in any way. This echoed with the Taoist philosophy of maintaining one’s natural character and preserving one’s purity and authenticity.

Wang Ying is from the School of Politics at Anhui Architecture University.

(edited by CHEN ALONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE