A short history of Chinese lamps

Changxin Palace Lamp was once placed at the Changxin Palace, residence of Empress Dowager Dou, a prominent figure in the Han Dynasty.

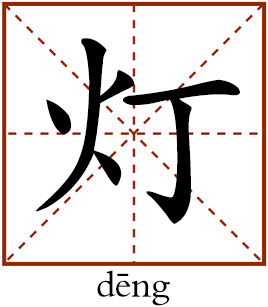

To illuminate themselves at night, ancient Chinese mostly used deng, meaning lamps or lanterns, or zhu, meaning candles. Red deng and zhu symbolize happiness. For those staying away from their hometowns, lamps and candles can also trigger homesickness.

Humanity trembled through numerous dark nights before it uncovered the secrets of fire. A lightning struck a big tree on a stormy night, lighting up the darkness and scaring away animals. Humanity gradually mastered the skill of using fire, protecting and guiding themselves at night. Mastering the skills of preserving and making fire laid the foundations for the creation and use of lamps.

Animal fat fueled the fire when prey was grilled. Illuminated by this, humanity created torches using animal oil and fat as fuels. The Book of Rites said “In ancient times, torches were used to light up the nights.” Honey had already been used during the Western Zhou Dynasty. Ancient Chinese wrapped strips of cloth around a stick and bathed it in honey. This new creation was called a “candle.” At that time, sweet herbs were added in the fat and oil, reducing the burning smell of animal fat and oil.

Pottery lamps were created as technology for manufacturing pottery advanced. Some scholars believe a trumpet-shaped mouth utensil unearthed at the Kuahuqiao site in Zhejiang Province which dates back more than 7,000 years, as one of the first pottery lamps. Others argued that a broad-mouthed utensil unearthed in a tomb from the Shang Dynasty was the earliest pottery lamp. Despite these debates, pottery lamps marked an early step in China’s history of illumination.

Lamps became exquisite in the Warring States Period (453-221 BCE). There were four major types of bronze lamps—lamps in the shape of both dou and gui cooking utensils, human-shaped lamps and tree-shaped lamps.

Lamps in the Qin and Han dynasties showed exquisite design and excellent manufacturing skills. The Changxin palace lamp unearthed in a tomb at Mancheng, which dates back to the Han Dynasty, has the shape of a palace maid. The head and arms of the maid can be disassembled. The lampshade can be opened and closed to adjust the light. The raising sleeve of the maid serves as a shade and her right arm serves as a chimney. Pragmatic, scientific and beautiful, the Changxin palace lamp demonstrates the wisdom and technology of people in the Han Dynasty.

Bronze lamps in the Qin and Han dynasties showed extraordinary talent and marked the first prosperous stage of the development of lighting facilities in ancient China. However, bronze lamps could only be enjoyed by staff at the royal palaces and members of aristocratic families.

The number of porcelain lamps increased between the Han and Tang dynasties, which was primarily from the third to sixth century, gradually replacing the dominant role of bronze lamps. Candles made of beeswax were widely used in the Tang and Song dynasties. In the late Song Dynasty and early Yuan Dynasty, people gradually mastered the skills of producing white wax. Candles made primarily of white wax came into use.

The development of porcelain in the Ming and Qing dynasties boosted the extrinsic beauty of lamps. British chemist Humphry Davy’s innovation of electric arc lamps in 1809 brought humanity into the age of electric lighting.

Baron lanterns were created by Chinese in the 20th century. Using kerosene as fuel and a wick dipped into the fuel, a baron lamp has a glass shade, sheltering the light from wind when walking outside. A baron lamp could adjust its light and be hung on a horse. In undeveloped rural areas where electricity blackouts were common, one kind of simple kerosene lantern made from a small pot with a cap was popular. A wick dipped into the fuel through a hole of the cap, this kind of lantern was very convenient but is rarely seen today.

Yue Jingjin is from the Department for the History of Science and Scientific Archaeology at University of Science and Technology of China.

(edited by CHEN ALONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE