Gender differences in views on love, marriage in modern Chinese literature

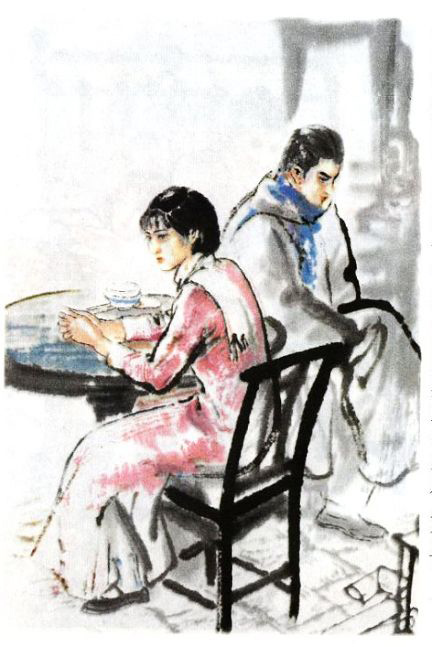

Illustration by Yao Youxin, a famous illustrator and portrait painter, for Lu Xun’s Regret for the Past

When people in love get married and become family, it is quite common to have some disillusionment with marriage. This is a common literary motif. It has especially been the subject of exploration in modern Chinese literature. In the early stages of the New Culture Movement, conflict between love and marriage had already been presented in description of family life. For instance, Bing Xin’s The Two Families discusses how to continue the “sacred” love in daily life, while Lu Xun’s Regret for the Past is an elegy of love eroded by marriage.

Looking back on the three decades of modern Chinese literature, we can see that male and female writers tended to adopt different perspectives on the root causes of the conflict between love and marriage.

L. Vorobyov, a scholar from the former Soviet Union, wrote in “The Philosophy of Love” that “the death of love is an old, universal question.” “The mandatory everyday routine and all sorts of tedious rules…will create an unbearable atmosphere, in which even the most loyal love could suffocate.” This is quite profound analysis, pointing to the incompatibility of mundane and spiritual life, which is to say that the repetitive and tedious nature of mundane life will inevitably lead to boredom that suffocates love.

We can say that all people who enter the “fortress besieged” of marriage have to undergo such a process. Marriage is compared to the “fortress besieged” mostly because of this. The majority of people might adapt quickly in spite of the distress. For those who have a higher demand for spiritual life or who are more sensitive, they might find it difficult to adapt. As such, they will feel depressed and disillusioned, and even rush out of the fortress besieged and abandon the love nest. This is represented in literature in works like Regret for the Past.

Compared with novels in ancient times, modern Chinese narrative literature features more depictions of love. At the same time, it is quite common to connect love with the pursuit of liberation of the mind and a free life. As such, love is further sanctified. The conflict between family life and love intensifies. When sacred love is worn away by mundane chores, and the suffocating atmosphere permeates the family, the couple, once in love, begins to harbor resentment against each other. Who is responsible for this?

Let’s have a look at the perspectives from the two genders.

Male perspectives

In the story Regret for the Past, although he is describing his remorse, Chuan-sheng seems to be blaming Tzu-chun for the failure of their love. Tzu-chun was stuck in the repetition and tedium of secular life. “Her house-keeping left her no time even to chat, much less to read or go out for walks.” With this, the spiritual life went into decline: “All Tzu-chun’s efforts seemed to be devoted to our meals ... Apparently she had forgotten all she had ever learned ... she paid no attention at all, but just went on munching away quite unconcerned.” In the eyes of Chuan-sheng, the once beautiful body of his lover became ugly. Her hands became rough, and her body grew plumper. “Perspiration made her short hair stick to her head,” and there was an icy expression in her eyes. Her spiritual life was so empty except for feeding the dog and the chicks and getting irritated by the landlady.

Then what about Chuan-sheng? He was struggling with the harsh circumstances. He was making desperate efforts writing and translating, but he was often interrupted by her. He even did not have enough to eat as Tzu-chun needed to save some food for the chicks and the dog.

Apparently, the man was trying to maintain the family life and felt nostalgic for the romantic love before. However, the woman became a slave to secular affairs, and then an accomplice, destroying everything the man had cherished.

In his novel The Quest for Love of Lao Lee, Lao She drew an even more detailed picture of men trapped in mundane family life. Of the two families, the Chang family becomes secular to the fullest extent. The family’s ultimate goal is to feed themselves. The family members’ spiritual lives also become so secularized that they do not even have any distress caused by the mundane life. This family, however, is an object of ridicule. Lao Lee once narrated the root reason for his agony. “What I pursue is a bit of a poetic life. Family, society, the nation and the world, all are realistic rather than poetic. The majority of women—whether they are married or single—are ordinary. Or, they are more ordinary than men. I want–even if just to have a look at—a woman who has not been damaged by reality, who is passionate like a poem, pleasant like some music and pure like an angel.”

He is distressed because there is no poetic life in the family, and women damaged by reality are held responsible for this. The family cannot enrich a man’s spiritual life because women are “more ordinary than men,” and they are “damaged by reality.” That is to say, when women are doing hard work keeping the house and involved in monotonous, repetitious toil, they fail to create anything valuable. Instead, what they do is destructive. This is Lao Lee’s idea about family life, which is representative of the author’s viewpoint to a certain extent.

Female views

Let’s see how female writers dealt with such conflict.

Examining peasant life, The Field of Life and Death by Xiao Hong gives the same account of how love diminishes. The author wrote about women’s agony associated with this process in the words of Chengye’s aunt, who narrates her craving for love as a young girl and also a man’s cruel change. “I would never listen to this melody. There is nothing reliable about a young man! Your uncle used to sing this when young, but now he never thinks about the past. That is like a dead tree that will never come back to life again. ”

There is another vivid description in the novel: “The woman tiptoes quietly out and stops at the door. Listening to the sound of the window paper, she becomes completely powerless and gray. In the courtyard, the dragonflies are dancing among the sunflowers. However, this is absolutely isolated from the young woman. ”

The warmth of family has faded completely and the woman’s spiritual world is totally drained. However, this is not because of her. She is not willing to experience this and wants to restore the past. However, she simply cannot change the man who is now immersed in farming and drinking. By depicting love, marriage and family life of two generations that follow a similar trajectory, Xiao Hong demonstrated her profound and bright thought. The cause of the tragedy is not any particular husband, but men as a whole. As such, Xiao Hong voiced women’s complaint.

Ten Years of Marriage by Su Qing shows a complete history of how the family breaks down. The couple gets married out of love, but the love diminishes and they grow apart. Compared with the aforementioned works by male writers, this novel not only depicts how the two genders behave differently when faced with the mundane life but also shows the man’s bad behavior when the woman tries to renew her spiritual life. When confronted with daily housework, the woman still bears the burden without hesitation although she feels bored. Her husband, on the other hand, does not appreciate this. He even refuses to take any economic responsibilities. He will not pay for the rice. The atmosphere in the family then begins to exacerbate. When the wife pursues her hobbies, the husband gets hostile for no reason. He locks the bookcase to prevent her from reading. When her first piece of work is published, she celebrates this with her husband with delicious dishes. However, the husband “has an icy expression after having the barbecued pork and the wine, throws that magazine aside and will not even bother to read it.” The man has not made any efforts to invigorate the family life. Rather, he destroys the woman’s hard work to build the material foundation and spiritual home. His narrowness and rudeness are not reasonable. Of course, the husband is responsible for the family’s breakdown.

An Autobiography of a Retired Woman by Pan Liudai portrays the tortuous process of the family’s breakdown. The husband is a disloyal pervert. Like the husband in Ten Years of Marriage, he has exactly the same attitude toward life’s burdens. As such, the family has been turned into hell for the woman. “He has pushed me to hell where I am fantasizing of life in heaven.” Regret for the Past and The Quest for Love of Lao Lee have similar descriptions. The difference here lies in the gender of the one who pushes the other to hell.

When approaching the same problems in a family, there are enormous differences between the two genders’ perspectives. This is partly because they have different experiences and partly because the two genders have taken different stands. As long as we take our own stand as the only one, we will inevitably have a biased perspective. As Simone de Beauvoir said, “The quarrel will go on as long as men and women fail to recognize each other as an equal.” This actually applies to literary creation, too. The transition from romantic love to the drudgery of family life is an eternal theme for humankind, and the only way to alleviate the negative impact is thinking beyond our own gender and seeking mutual understanding. This transcendence is also the formula for literary works to take a higher stand and overcome the bias. The author needs to transcend the stands of the characters and elevate to a point to have a bird’s-eye view of the two genders, and love and marriage.

Chen Qianli is an associate professor from the School of Literature at Nankai University.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE