History of North China Plain offers lessons for development

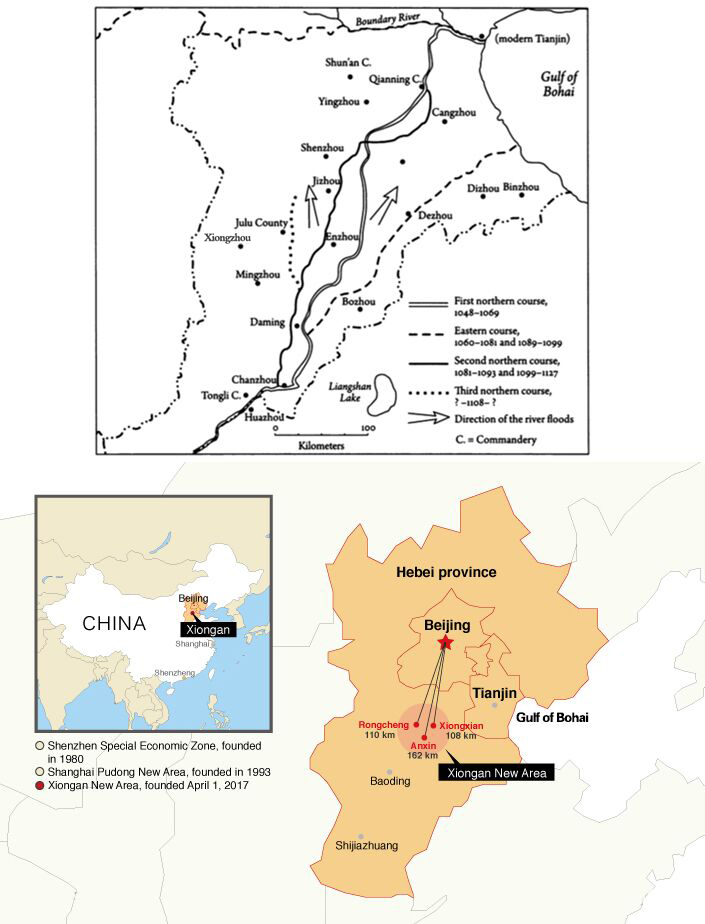

The Yellow River’s courses and the direction of the floods in Hebei: 1048-1128, and the location map of Xiongan New Area (SOURCE: ZHANG LING(ABOVE) /CAIXIN (BOTTOM))

Zhang received the award for her book on April 1. Coincidentally, she read in the news at almost the same time that China had announced plans for the Xiongan New Area in Hebei Province. The new area is to be located about 100 kilometers southwest of downtown Beijing and will include three counties: Xiongxian, Anxin and Rongcheng. It will be as important as the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in the South and the Shanghai Pudong New Area in the East.

“Maybe 99.9 percent of Chinese people did not expect the policy,” said Zhang Ling, a female scholar whose research focus is the Hebei Plain in the Northern Song Dynasty. Though her research focused on the medieval history of the area, she confessed she knew little about the latest developments there.

Dramatic changes

Xiongxian County has begun to change in all aspects since the plan to construct the Xiongan New Area was announced.

The county is a typical rural area mostly dominated by simple houses, farmland and agricultural businesses. Since the announcement, the streets have become bustling and property prices seem to be soaring. This reminds Zhang of Xiongzhou in the Northern Song Dynasty, which also underwent a dramatic change about 1,000 years ago, which brought about destruction and sluggishness.

The course of the Yellow River roughly marked the boundary line of the Hebei Plain, but the river suddenly overflowed its banks in 1048 at present-day Puyang in Henan Province and turned its course to the Hebei Plain. The river’s course went northward, extended to the lakes in Xiongzhou and Bazhou and finally emptied into the Gulf of Bohai at modern Tianjin. The Yellow River and Xiongzhou region, which were more than 200 kilometers away, suddenly collided. The environmental phenomenon was “so dramatic” to Zhang. This idea was behind the subtitle of her book: an environmental drama in the Northern Song Dynasty.

Floods drowned villages and farmlands, and at least 20 percent of Hebei Province’s residents lost their lives. Forced from their homes, they became refugees and 80 to 90 percent died during the harsh journey. Bodies lined the road, stretching for more than 500 kilometers. One year later, violent floods led to crop failure for three consecutive farming seasons. Historical documents recorded that even fathers and sons were killing each other for food. The Yellow River breached its banks again and swallowed up the whole county town of Julu. About 800 years later, people rediscovered the buried ancient city as they were digging a well in response to a severe drought.

In 2013, Zhang came to the banks of the Yellow River for the first time, which was her only first-hand experience with this piece of land. Scholars of modern environmental history may find traces left in the past 200 years on the earth’s surface, but there is no need for historical scholars to conduct field investigations. However, Zhang felt she “must walk along the Yellow River to have a thorough interaction with the river flow and land.”

Everlasting impacts

The flooding of Xiongzhou by the Yellow River lasted for 80 years and its influence lingers to this day in the form of lakes and wetlands that emerged at the time.

Xiongzhou was a frontier stronghold on the Hebei Plain in the Northern Song Dynasty. It had a large number of water networks consisting of lakes, swamps and paddy fields. It is estimated that the defense system utilizing these water networks extended for more than 400 kilometers, with a total area of more than 10,000 square kilometers, including present-day Baiyangdian, one of the largest freshwater wetlands in North China. These water networks not only blocked Khitan cavalry but also reduced the number of garrison soldiers needed, which cut defense costs.

“The shifting of the Yellow River brought about a great quantity of water in a short term. The expanded area of wetlands consolidated the border,” Zhang said, “But in the long run, the silt brought by the river flow accelerated the process of sedimentation and draining of these ponds, leading to numerous consequences.” Floods poured in a stream on the flat Hebei Plain. The land was increasingly salinized because there was no way to drain waterlogged fields. As a result, numerous lakes and ponds silted up and quickly became barren. The fertile land on the Hebei Plain all turned into desert, according to historical materials.

Zhang Ling wrote in her book that the subsequent soil erosion made land desertification a serious environmental problem that has plagued the Hebei Plain since the 11th century.

The Song Dynasty officials ordered the diversion of the Yellow River to the south in 1194 with the goal of preventing the Jin military from attacking Kaifeng, the capital city. After the river’s course was diverted, the north became a source of sand, and sandstorms ravaged all of North China every time strong winds blew. The area suffered from the problem for nearly nine centuries, slowing down agricultural and economic development as well as population growth.

Focus of history

On hearing about the establishment of the new area, part of efforts to create a Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei city cluster, the first idea that came to Zhang’s mind is that “Beijing is too huge. The establishment of Xiongan New Area will scatter the urban functions that have outstripped Beijing’s ability to handle them.”

This decision “seems unavoidable,” she said. As a scholar of environmental history, Zhang argues that “urbanization may not bring positive consequences.” Rapid, unrestricted urbanization may lead to fierce competition for resources, greatly hurting the natural environment and the ecosystem. The government has to properly deal with a host of associated challenges, such as accommodating the influx of migrants, dealing with local water pollution, and managing resource competition among various social group, she said.

Many of Zhang’s studies have revealed that the effects of human environmental damage are often delayed and cannot be observed in the short term. “The consequences may only become visible 10, 30 or 50 years later and impact the environment of our offspring. We often neglect the dangers that are beyond our imagination and recognition,” Zhang said.

A total of 89 floods took place in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River during the reign of the Northern Song Dynasty—about once every two years. Zhang Ling said that the only effective way to resist flood water was to build dams using wood, soil and stone at that time. In order to reinforce the dams, local residents cut trees and uprooted bushes in the nearby mountains. A large quantity of silt was blown into the streams and contributed to the dark color of the Yellow River.

“The environmental problems of the Yellow River and Hebei Plain are like a black hole,” Zhang said. She wrote in her book that the Northern Song Dynasty was eager to tame the Yellow River and create a comfortable natural environment. Their efforts were in vain, which resulted in deterioration for the ecological system and disasters of human society. Zhang won the prize because she described how political deliberation can impact the natural environment.

“People are only a tiny part of an enormous world, so they are not necessarily the protagonist,” Zhang said, arguing that “history is not only created by people but also formed by the interaction between humans and nature. Environmental history has expanded the definition of history.”

“Environmental history aims to change how people see the world. To some extent, economic growth is not the only dominant factor, and individual development is not the ultimate goal. Based on this understanding, the world may begin to change from now on,” Zhang added.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE