Firecrackers, dramas: Symbols of traditional communication in villages

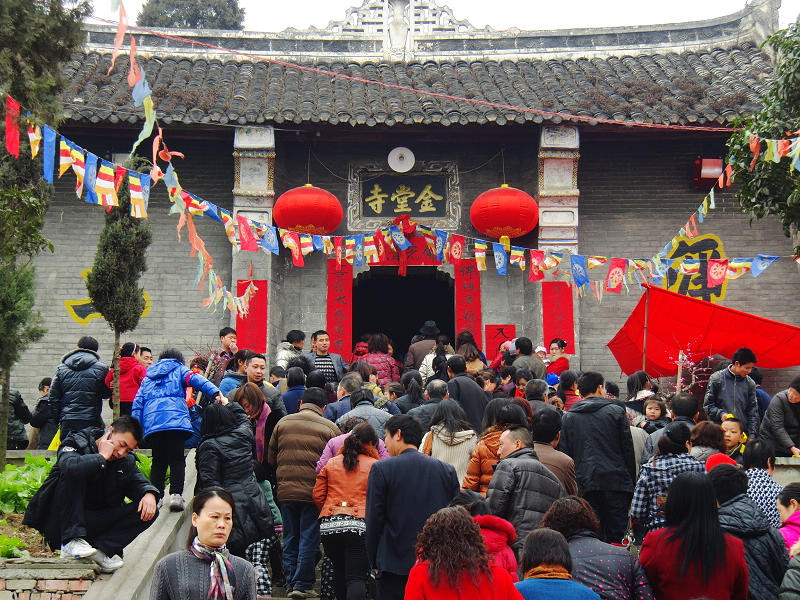

People gather at the temple fair for the Longtaitou Festival, a traditional Chinese festival held on the second day of the second lunar month, in a village in Shaanxi Province. Before the year 2000, when mobile phones were still rare, firecrackers served as a medium for disseminating information in addition to their role as entertainment and a ritual component. Villagers decided when to go to the temple fair by listening to the sound of firecrackers.

In the mass communication era, information is imparted and exchanged on a large scale using an array of media, including newspapers, magazines, books, radio, television, film and the Internet. But in some Chinese villages, information is still conveyed in traditional ways, such as acoustic and optical signals sent via firecrackers, gongs and drums, a system of recording agricultural events using knots, and drama performances for entertainment and education. These traditional modes of transmission, however, are not included into contemporary mainstream communication studies.

From the perspective of daily life and practices, Bu Wei, a research fellow from the Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, refers to dance, folk songs, ballads, paintings, legends, puppet shows, operas, blackboards or wall posters in villages collectively as “traditional media.” She said traditional media are rooted in local culture. They provide an instrument of information dissemination and entertainment for a group that has no access to mass media or is unwilling or unable to speak through mass media.

Throughout history, traditional media have become invested with cultural connotations and internalized as rituals, lifestyles, ways of thinking and values for villagers. Therefore, studying traditional media in villages will be conducive to understanding the emotional structure of villagers.

Longitudinal ethnographic investigation in villages shows that most traditional media imply collectivism. Borrowing the concept of a solidarity economy developed by Ethan Miller of Grassroots Economic Organizing, the writer put forward the concept of a “solidarity medium” to refer to traditional media rooted in production, rural lifestyles and collectivism.

Ropes to keep records

In villages, folk customs and arts are derived from daily life, production and labor. In villages in southern China, ropes are mainly made of straw. Since ancient times, villagers have formed mutual aid teams when planting and harvesting rice. Such a collective behavior arose as a spontaneous strategy for production. Villagers twist pieces of straw into ropes and use them to bind things together, so ropes gradually became a symbol of unity.

In addition to bows, arrows and fishing nets, the earliest hunters and fishermen also needed ropes to bind prey. By using ropes, primitive humans fastened animal skins to their bodies to cover themselves and keep warm. Almost all tools and other items for production and daily life were combined or connected with ropes.

The extensive use of ropes in human production and living gave special meanings to ropes, which later began to function as a means of communication. Tying knots to keep a record of events is one of the oldest forms of human expression. The Chinese character jie, meaning “tying knots,” is used in phrases to mean becoming united or banding together. In addition, since jie sounds similar to ji, meaning “auspicious,” tying knots became a way to express wishes and blessings. Moreover, the technique of using instruments like spinning tops to twist ropes together could be said to symbolize the process of human social organizations developing from a single ethnic group to multiple nations, and from tribes to a great country.

Firecrackers to release signals

In ancient times, sight and sound were used to signal other people from a distance. Initially used as signals, firecrackers, gongs, drums and bonfires came to play a significant role in later rituals and ceremonies. Fire can create an exciting atmosphere but only in the evening. Also, for safety reasons, there are limits to where and when people can set fires. Therefore, villagers prefer to communicate through sound, increasingly highlighting the role of firecrackers, gongs and drums in rituals and ceremonies.

In the field investigation of a village in northern Shaanxi Province, villagers recalled that before the year 2000, when mobile phones were still rare, listening to the sound of firecrackers was an important way to tell time and communicate during the temple fair for the Longtaitou Festival, a traditional Chinese festival held on the second day of the second lunar month. The tradition of the temple fair goes back to ancient times. It was the time for the people to make sacrifices to village deities, and the ritual’s location gradually evolved into a marketplace for people to exchange products as well as stage cultural performances.

Around 10 a.m., many people, mostly young people, gather in the temple to light firecrackers with plastic bags covering them. When they explode, the plastic bags are blasted into pieces or fly into the sky like kites. Upon hearing the sound, wives tell their families to hurry up and finish eating. After the fifth sound, they get ready to leave. And they should arrive at the temple by the tenth explosion.

About one hour later, villagers will arrive at the temple one after the other. It is clear that villagers have jointly encoded and decoded the implications of firecrackers in the process of communication. The process shows a tendency toward collectivism. With the help of firecrackers, the temple fair proceeds in an orderly way. Firecrackers serve as a medium for disseminating information in addition to their role as entertainment and a ritual component.

Dramas for gatherings

Dramas, shadow plays and puppet shows are often seen as the origin of TV dramas and films. Onstage performances that integrate plot, music and art can realize the goals of education and entertainment. Various forms, enriched content and multiple effects make dramas a mature medium. Scholars on communication studies focus on drama as a communication medium and its contribution to national development while paying little attention to solidarity and collectivism embodied in dramas.

Above all, the content is produced by generations of efforts. Many senior artists recalled that in addition to learning from masters, young people, under the influence of village dramas since childhood, used to play with shovels to practice performing while working in the fields.

Due to a low level of literacy, there are no scripts, so the repertoire is passed down orally. Performers of later generations may add new content based on their own understanding. Thus, the creation and reimagining of dramas is a task that is jointly finished by generations of artists. Live performances are also a result of teamwork.

For thousands of years, the course of every villager’s life has been nearly the same: being born, reaching adulthood, getting married, having children and dying. Dramas are used to celebrate or commemorate every stage of life. Thus, dramas punctuate the time axis of one’s life, through which one would know what she or he had experienced and what was left for him or her.

Generation by generation, they constitute the history, present and future of villages. For each celebration or commemoration ceremony, other villagers come to watch the performance. This allows every villager to participate in the lives of others. Through dramas, the whole village has become a cohesive community.

Before televisions became common, villagers farmed in the daytime and went to their homes and beds after dark. They had entertainment only during gatherings when they did not need to work, such as temple fairs, weddings, funerals and festivals. Villagers often drank wine and played the finger-guessing game while watching dramas. After TV emerged, they were able to watch TV every night at home. Gradually, entertainment lost its character as a collective activity but has become a part of one’s daily life.

Significance of solidarity medium

Studying the solidarity medium of villages has theoretical and practical significance. The theme of the times for contemporary Chinese villages is cooperation in human and land resources as well as production modes and market management. Various cooperatives have sprung up, bringing benefits to farmers and giving them more opportunities to survive in economic globalization, urbanization and marketization.

Communication studies should respond to major issues of the times by pointing out the future direction of social development. The solidarity medium has united villagers together. Research on the subject will shed light on how to integrate new cultural communication behaviors with political and economic activities.

Research on the solidarity medium can promote local communication studies, avoiding the tendency to apply mechanical mainstream theories to rural communication. By including those common but neglected communication behaviors into the sphere of communication studies, native theories based on Chinese traditions and realities can be created, thus providing a new communication paradigm for China and even the world.

Sha Yao is from the Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE