Chinese characters: Handwriting styles shed light upon different personalities

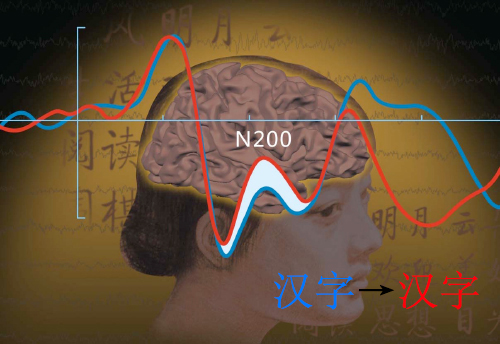

In the experiment on the brain’s response to Chinese characters, we can observe a unique centro-parietal N200 response. This N200 response shows a clear and large amplitude enhancement upon word repetition. The discovery of the centro-parietal N200 reflects that visual analysis appears early in the identification of the orthography of Chinese characters.

In human history, drawings representing an object, concept or sound were used as the earliest form of writing, which later developed into hieroglyphics. Around the 15th century, the writing system using picture symbols was gradually replaced by phonography, a writing system that represents sounds by individual symbols, such as the English, Russian and Arabic languages.

In the evolution, however, the Chinese language has retained visual features. The writing forms of Chinese characters can still shed light upon their meanings. As a result, reading and writing Chinese characters may give rise to complicated psychological activities and emotional experiences.

Graphic, spatial features

Each hemisphere of the brain specializes in certain behaviors. The left hemisphere is dominant in logic abilities and in language--processing what you hear and handling most of the duties of speaking. The right hemisphere is mainly in charge of spatial abilities, and can help us comprehend visual imagery and make sense of what we see. Experiments show the right side of the brain is more active than the left side when writing Chinese characters, while it is on the contrary when writing English words. This indicates Chinese characters contain graphical information.

This is also evidenced by the recent application of technologies on processing electrophysiological signals in neurophysiological studies. Psychologist Zhang Xuexin from the Chinese University of Hong Kong proposed a meaning-spelling theory that Chinese characters are created by combining units of meaning, which is different from phonography languages which are composed of units of sound.

In the experiment, which compared the brain’s response to Chinese characters vs. non-characters when read by Chinese speakers, we can observe the centro-parietal N200 response. This N200 response seems to be specific to Chinese as no similar effects had been reported in word recognition studies involving alphabetic scripts under similar experimental conditions. This N200 response reflects that visual analysis appears early in the identification of the orthography of the Chinese characters.

In cognitive neuroscience, different letters and strokes are classified as high frequency spatial information, while linear arrangements of letters as well as spatial arrangements of strokes and radicals are classified as low frequency spatial information. Alphabetic words are created in a linear fashion. Take English for instance, a combination of different letters and the sequential order of letters are used to distinguish between words (e.g., dear vs. deer; dog vs. god). Chinese characters are created in a dimensional way through spatial arrangements of different strokes or radicals (e.g., 玉vs.王; 土 vs. 干; 呆vs.杏).

Zhou Aibao, a professor of psychology from Northwest Normal University, found that Chinese characters trigger a N100 response in the part of the brain that controls low frequency spatial information, which never appears in the early processing of alphabetic writing. This indicates that the brain is undergoing a more complicated course involving the processing of low frequency spatial information under the stimulus of Chinese characters compared with alphabetic writing.

Relationship between handwriting, personalities

Individual handwriting styles convey a vast amount of information about the person. Related studies show that seeing one’s handwriting will set off a series of psychological activities in his or her mind, such as pondering how people wrote the characters and whether they write them well. And experiments show that the brain is processing and integrating information about the handwriting styles at the same time.

Studies show that personalities can be reflected in what size the written characters are, how much strength is used, how much space there is between characters and how fast a person writes. Yang Guoshu, a famous psychologist in Taiwan, found through studies that people, regardless of gender, who write in larger size are more likely to be introverted, but for male respondents, people who write more illegibly are more likely to be extroverted. Gao Shangren, a professor of psychology from the University of Hong Kong, found that people who write using more strength are more likely to be extroverted, while those who write using less strength are more likely to be introverted.

Meng Qingmao, a psychological professor from Beijing Normal University, and other researchers found that people who write horizontal strokes using less strength are more likely to lack confidence, while those who write horizontal strokes using more strength are more likely to be bold. Moreover, people who write vertical strokes using more strength find it easier to get irritable and anxious, and respond strongly under stimulus. By contrast, those who write vertical strokes using less strength are easier to calm down.

Calligrapher Fan Lie found that people who leave more space in the left when writing are more likely to be patient but less independent. In addition, studies show that people who write fast are more impulsive, while those who write slowly are more likely to be steady-going.

‘Calligraphy therapy’

To produce clear handwriting, writers must adopt the right posture, concentrate and breathe evenly, which can help stabilize mood and enhance perceptual sensitivity. This is also an effective way to relieve people of tension and bring about positive emotions in people. Research indicates that people who practice calligraphy tend to have a longer pulse duration and lower blood pressure compared with those who do not practice calligraphy. This indicates that calligraphic practices could improve both mental and physical health.

When practicing calligraphy, the brain produces relaxing neurohormones. This can be evidenced by experiments. In the experiments, people who practice calligraphy have weaker average brain activation when sitting or writing than those who do not practice calligraphy.

In an experiment on the elderly, after they practice calligraphy for 30 minutes, the elderly who often practice calligraphy recorded a positive shift of N200 and P300, but no obvious changes happened for the group which was not allowed to do the practice. N200 reflects the early reaction under stimulus, while P300 reflects the advanced stage of processing information. The results show that calligraphy can help improve alertness and concentration. Thus, calligraphy could ease the decline in perceptual abilities and even slow the aging process.

The uniqueness of Chinese characters can activate the right side of the brain in individual cognitive processing. Moreover, appreciating one’s handwriting evokes reflections about the self. The process of writing Chinese characters is a series of coordinated and complicated actions accomplished together by the pen, fingers, the wrist, the elbow and the arm under the instructions of the brain. In the process, concentrated attention is needed, and the person’s heart rate, blood pressure and breath frequency decrease. In addition, processing handwriting information can enhance personal cognitive capabilities. In conclusion, calligraphy is conducive to realizing harmonious integration of mind, energy and soul.

Chinese characters are a representative of Chinese culture. Thus, promoting calligraphy can help carry forward excellent traditional Chinese culture and build national confidence. Practicing calligraphy for a long time can improve mental and physical health. Therefore, it is a matter of well-being to advocate for the study of Chinese characters.

Xia Ruixue and Wang Wei are from the School of Psychology at Northwest Normal University in Lanzhou, capital of Gansu Province.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE