Tearing down walls: Notions of public space change with society

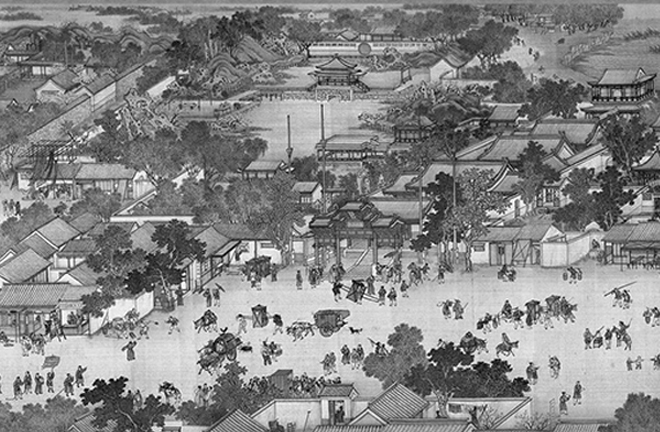

Pictured above is a section of the famous painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival depicting crowded shops along the street by the Bianhe River. With commercial development in the Northern Song Dynasty, enclosing walls were removed for space to open up shops, breaking down the separation of walled marketplaces and residential areas.

A guideline on urban planning issued by the State Council in February this year has sparked debate about a proposal to integrate gated residential communities into the public road system. In addition to being a functional element of construction, walls have always had cultural connotations, and they symbolize a model of social governance.

In ancient times, there were two kinds of walls: the city wall and the courtyard wall. The wall encircling the city was used for military defense while the walls around courtyards meant security for households.

In households, walls formed a closed space that provided an arena for the practice of etiquette and the establishment of organized authority. Thus, ethics governing human relations took shape, laying the foundation for political rule and governance.

In an anecdote conveyed in the Analects of Confucius, Confucius stood in the hall and saw his son pass by. Standing in the hall, the father could observe and govern everything that took place in the household. In traditional Confucian ethics, a man’s courtyard was “his castle.”

Ancient residential pattern

According to the Book of Rites, in ancient times, the city was divided into numerous basic precincts in a checkerboard pattern. A basic precinct was called a li and later called a fang. Each li or fang was walled and gated. And there was an official appointed to guard the gate on each side of the central avenue. Throughout history, such a residential pattern was maintained despite the growth in the amount of households residing in the precinct. The city layout was depicted in the works of renowned Chinese poet Li Bai (701–762) and Bai Juyi (772–846).

Under the walled li-fang system, the political power of the state was able to make its way into each household. The residential pattern, together with the system of grouping 10 households as the basic unit for administrative management, formed the fundamental way for the nation to govern society on the local level.

This helped government authorities to crack down on illegal and criminal activities. It enabled the state to easily levy taxes and mobilize labor while laying the basis for neighborhoods. The design of the li-fang system created a well-ordered space, which ensured effective control over people and their lives. Furthermore, it helped consolidate the Confucian ideas of responsibilities and obligations, which was hard to realize by political power alone.

Enclosed marketplace

It should be noted that the li-fang system emphasized the separation of the marketplace and the residential areas. People within the residential areas were not allowed to set up shops at will.

According to related documents and archaeological materials, marketplaces enclosed by walls appeared during the Warring States Period (475-221 BCE). The gate of the marketplace opened and closed at regular hours in the morning and evening.

At the center of the marketplace was a tower building flying a flag. Raising the flag was a signal that shops were open. In addition, the building also served as a place for designated officials to observe, supervise and govern the market. At that time, because agriculture was considered more vital than commerce, the central authority introduced strict management procedures to govern commercial activities.

In the middle of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the development of productive forces increased the supply of products. In particular, a new tax was introduced that would be levied twice per year directly on money instead of on materials, such as grain and cloth, which greatly pushed forward prosperity of the market.

Business hours were extended, and night markets soon appeared, violating the restrictions that limited transactions to daytime. In that context, the traditional li-fang system could no longer support increasing economic activities. In some places, some residential areas began to open stalls, while in other places, shopkeepers knocked down enclosing walls for space.

By the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), in the capital Bianjing, modern-day Kaifeng, various shops opened one after another along the street by the Bianhe River, forming a scene that was captured in the famous painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival. At the end of the period, the government began taxing shops that occupied the street, giving official sanction to the practice of setting up shops there.

Later, some districts were directly designated to serve as open markets. Gradually, the traditional residential pattern gave way to open streets and alleys. The removal of enclosing walls was not only a result of the reform in Tang and Song dynasties but also an inevitable outcome of commercial development, economic progress and social openness.

Establishment of danwei

In contemporary China, walls also play a significant role. From the removal of old city walls, the establishment of walled organizations to the appearance of gated communities, the construction and deconstruction of walls reflects the development of a city and the changes in the structure of government. The old city walls were a symbol of conservative power in old society and were dismantled to remove obstacles to industrial development.

Meanwhile, new walls have been set up to form various units. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, a planned economy was implemented. And the city was divided into all kinds of units, known as “danwei,” under unified national management.

Each danwei was made up of an administrative area and a living area. The living area usually included a shop, a vegetable market, a primary school and sometimes even a secondary school, a playground, a canteen, a public bathhouse and a hospital. In such a unit, the staff worked to obtain economic returns and achieve a unified social identity. In addition, they had access to forms of welfare, such as housing and medical services.

Moreover, the danwei provided employment opportunities for their children. Using this model, the nation was able to organize, manage, cultivate and educate its members.

Emergence of communities

When market economic reform began in the 1980s, the center of city life was shifted from units to blocks. The market economy replaced the distribution system, which has sped up the reform of the housing system, and commercial communities came into being.

Similar to the unit courtyards, gated communities are encircled by walls, and there are catering centers, fitness areas, kindergartens and convenience stores. But, people residing in the community may have different backgrounds and jobs.

With economic growth, urban communities have taken on a more luxurious, cosmopolitan character, featuring taller walls and more security guards as well as more advanced monitoring and access-control system. People pursue comfort and security within the enclosed communities. In particular, the rising middle-income group regards the commercial community as a status symbol that separates them from migrants and blue-collar workers who cannot afford it.

However, a real sense of security cannot be obtained by setting up walls. The walls cannot free people from the dangers of social disorder and inequality. At the same time, transportation and interpersonal communication problems will not be solved by simply dismantling the walls.

It is imperative to closely examine the public and private dimensions of space and formulate related legislation while seizing the opportunity to use the debate over walls as a “teachable” moment. The government should make it a priority to craft a public space policy that satisfies the changing needs of the people and better promotes social development.

Zhang Yujia is an associate research fellow from the Institute of Philosophy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE