Qing gang policy offers lessons for today

How Qing Court Dealt With Gangs

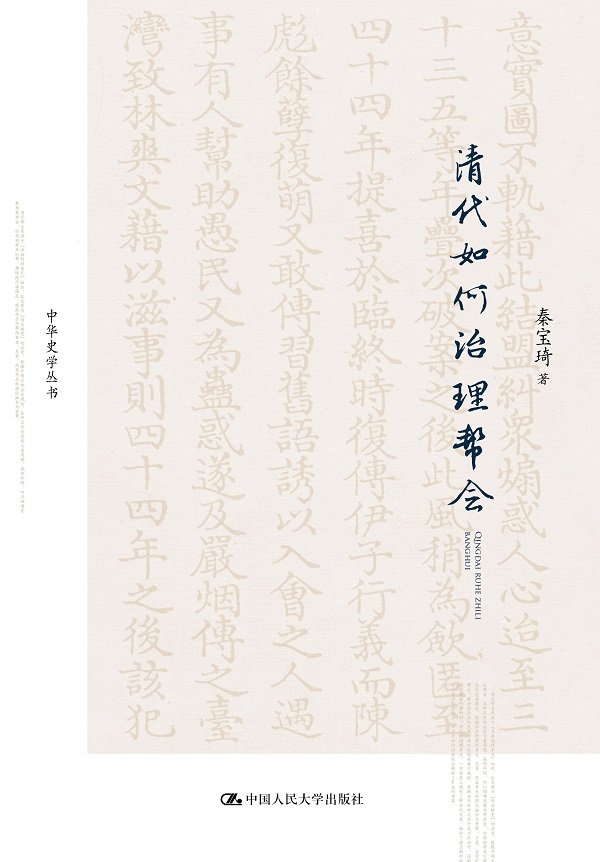

Author: Qin Baoqi

Publisher: China Renmin University Press

The Bund, a Hong Kong period drama, has captivated viewers across the nation with vivid depictsions of love and the quests for vengeance in the Shanghai underworld. However, the history of gangs in modern China and their influence on society is far more intriguing, complex and fascinating than even the plots in TV dramas.

The infamous Green Gang, a secret society which engaged in criminal and political activity in Shanghai during the early 20th century, is quite representative of that chaotic period of Chinese history. Huang Jinrong, Du Yuesheng and Zhang Xiaolin, known as the “three Shanghai tycoons,” started as young and greedy hooligans before rising to become the leaders of the gang and in that sense were the ultimate Chinese “godfathers.” Not only did they build connections with government officials, but they actually had a say in national political and military affairs. Such banditry and unrest attracted substantial attention from several generations of researchers.

However, the expansion of gangs during the period of the Republic of China (1912-1949) was no accident. It dates back to the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) and is closely related to the way the Qing court dealt with them.

As the author puts it, formulating an objective evaluation of Qing rulers’ policies toward gangs is a challenge for historians. On the one hand, some folk societies were founded for the purpose of mutual assistance and self-defense by the underclass. They mainly targeted local landlords, evil gentry, corrupt officials and protested against foreign invaders, striving to make a living and fight for social justice, which should be given some “understanding sympathy” as famous historian Chen Yange once advocated. Qing rulers, however, blindly imposed harsh repressive measures on all societies. It was indeed against the will of the people, unjust, and should be denied and condemned.

On the other hand, gangs in the Qing Dynasty were committed to protecting the interests of specific groups, thus unavoidably hurting ordinary people along the way. According to documented records, the majority of the victims were people from the vulnerable middle and lower classes, including farmers, especially rich farmers with some savings, craftsmen and small vendors. In this light, the Qing court’s efforts to stamp out gang activities were conducive to maintaining social order and ensuring people’s incomes, which should be affirmed.

In addition, the author analyzed the tendency to treat all social organizations in the Qing era as organized crime or Triads, arguing that only some gangs turned into Triads and the one-size-fit-all approach is faulty.

The book systematically goes through the evolution of the Qing court’s policy toward gangs, starting from forbidding sworn brotherhoods by law during the reign of Emperor Shunzhi (1644-61), hunting down the Tiandihui, literally the Society of the Heaven and the Earth, during the middle of the Qing Dynasty, to the indiscriminate elimination of various gangs at the end of the Qing Dynasty.

History is a mirror of reality and the essons learned in the way Qing court dealt with gangs can offer some suggestions to enlighten the present.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE