History of Russian lit in China short but profound

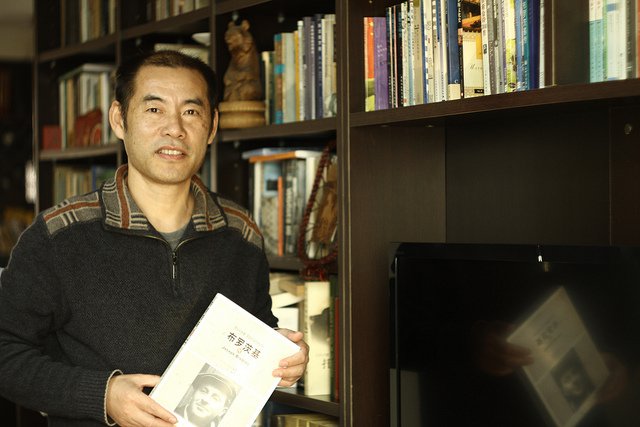

Liu Wenfei (1959- ) is a professor at Capital Normal University and president of China’s Russian Literary Research Association.

Chen Jianhua (1947- ) is the director of the Institute of Foreign Literature and Comparative Literature at East China Normal University.

On Nov. 4, Russian President Vladimir Putin awarded Chinese scholar Liu Wenfei the Order of Friendship for his contributions to Sino-Russian literary exchanges. Liu told a CSST reporter that the Order of Friendship is not only a personal honor but also a recognition of the work of all Chinese researchers in Russian literature. He added that professor Chen Jianhua is one of the most outstanding authorities on the history of Sino-Russian cultural exchanges, so CSST decided to talk to both scholars about Russia’s influence on Chinese society.

CSST: How was Russian literature introduced to China?

Liu: Compared to other neighboring countries, such as India and Japan, it took China a long time to begin literary exchanges with Russia, which only started around the turn of the 19th century. Based on modern Chinese translator and foreign literary expert Ge Baoquan’s investigation, the earliest Russian literary works introduced to China were three of Ivan Andreyevich Krylov’s fables, which were published in the Shanghai Guangxuehui or Christian Literature Society’s magazine Investigation of Russian Politics and Customs in 1900. Professor Chen conducted thorough studies and he found evidence that Russian literature was introduced 30 years earlier than scholars had previously thought.

Chen: The earliest Russian literary work translated into Chinese was American missionary William Alexander Parsons Martin’s Russian Fables. His translation was published in the initial issue of The Peking Magazine in August 1872, which I discovered at the Xujiahui Library in Shanghai in the 1990s.

Liu: The first separate edition of Chinese translation of Russian literature was Alexander Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter, which was published by Shanghai Daxuan Publishing House in 1903. At that time, Russian literary works introduced to China were translated from English and Japanese versions instead of the originals.

Chen: The majority of these works were translated from Japanese versions by Chinese students in Japan because Japan brought in Russian literary works 20 years earlier than China. Also, the quantity of these translated works was small but its quality was high because most of them were from Russian classic writers, such as Pushkin, Tolstoy, Lermontov and Chekhov. Furthermore, most Chinese who paid attention to Russian literature at that time were active in the intellectual community, and the representatives are Liang Qichao, Wang Guowei, Gu Hongming and Li Dazhao.

CSST: In the 1980s, as the reform and opening up kicked off, China comprehensively began to introduce foreign literary works, and the introduction of Russian literature to China reached its zenith. So what were the main characteristics of Russian literary translation at that time?

Chen: In the early and mid-1980s, Russian and Soviet literature accounted for 20 percent to 30 percent of foreign literary works published in China. At the beginning of the 1980s, Western literature had not been introduced to China on a large scale, but Russian and Soviet literature was the first to achieve widespread popularity. Because of historical ties between the two countries, many Chinese were proficient in the Russian language and many editor-in-chiefs and editors learned to speak Russian at college. So they were very interested in publishing Russian and Soviet literary works and published very quickly. Ehrenburg’s Thaw, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Aitmatov’s The White Steamboat were printed in yellow book format, which was a form of paperback for internal publication in China that first became common in the mid- and late-1950s.

Liu: During this period, the translation of Russian literature in China was not only large in scale but also gradually began to take on the following characteristic: First, its object mainly focused on contemporary Soviet literary works. Among thousands of translations, contemporary Soviet writers’ works accounted for 60 percent or 70 percent. Second, it began to take the form of systematic and academic translations. Many large-scale collections have been published. For example, People’s Literature Publishing House released 20 volumes of the Collected Works of Gorky and 17 volumes of the Collected Works of Tolstoy. Many other Russian writers’ complete works have been published as well. It seems to prove that Chinese translation of Russian literature has become nearly exhaustive. Finally, a number of academic studies have been conducted on the basis of large-scale translations. At that time, founders of China’s Russian literary translation and studies, such as Jiang Chunfang (1912-1987), Cao Jinghua (1897-1987), Ge Baoquan (1913-2000) and Ye Shuifu (1920-2002), were living and in good health. And those scholars who had studied in the USSR in the 1950s and were forced to stop their research there took this opportunity to conduct research again. Scholars who enrolled in universities after the reform and opening up successively joined the research team of China’s Russian literary translation and studies. A gathering of these three generations of scholars jointly facilitated an unprecedented flourishing of China’s Russian literary translation and studies.

CSST: After the collapse of the Soviet Union, how have Chinese scholars of Russian literature continued to work and maintain a focus on Russian literature?

Liu: Although less attention is being paid to Russian literature, the work of Chinese scholars has not been impacted so much and instead has achieved rich fruits. Firstly, even though the publication market is not as good as before, important Russian writers and their representative works remain a subject of interest for Chinese translators and researchers since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Each year, several dozen contemporary Russian literary works come out. New books of Russian mainstream writers, such as Solzhenitsyn, Rasputin, Makanin, Viktor Erofeyev, Ulitskaya and Pelevin have been introduced to China, which has led to renewed interest in Russian literature. Second, Russian literature has been accepted by China with a more serious and rational attitude. This has manifested in the expansion of Chinese research on Russian literature and the overall improvement of research quality. Now Russian literary researchers have carried on their predecessors’ legacy and gradually developed their own styles that are distinctive from those of their predecessors. Although the number of readers of Russian literature has declined, those who continue to read are true lovers of literature, which demonstrates that Russian literature has returned to the field of literature instead of being shaped by political, historical or other factors.

CSST: It is generally acknowledged that Russian literature is the literature of morality, humanitarianism and Tolstoy. What impact has this literary tradition, especially Russian critical realistic literature in the 19th century, had on Chinese writers?

Chen: This influence has existed for a long time. Tolstoy’s literature has greatly influenced several generations of Chinese writers with its distinct democratic awareness; strong moral strength; exploration of the significance of society, human nature and life; epic and magnificent atmosphere; broad coverage, and loose but stable structure. Wang Furen, a professor of Chinese literature, once indicated that Lu Xun’s classical Chinese novel Reminiscence published in Novel Monthly in 1913 clearly revealed the impact of Russian realistic literature, and Lu’s early works can be traced to roots in Russian literature. Mao Dun said that the development of the structural layout, plotline and multiple lines of his novel Midnight benefited from War and Peace in particular. Ba Jin wrote in the preface of The Family: “Several years ago, I shed tears upon finishing Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection and wrote on the title page that life itself is a tragedy.” The female character in The Family and her miserable life, to some extent, is inspired by Maslova in Resurrection.

Wu He is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE