‘Gunter’s Winter’: Peak of Latin America’s post-Boom literature

The translator of the Chinese version of Gunter’s Winter Yin Chengdong is awarded an honorary doctorate degree by Juan Manuel Marcos, the rector of the University of the North in Paraguay and author of Gunter’s Winter.

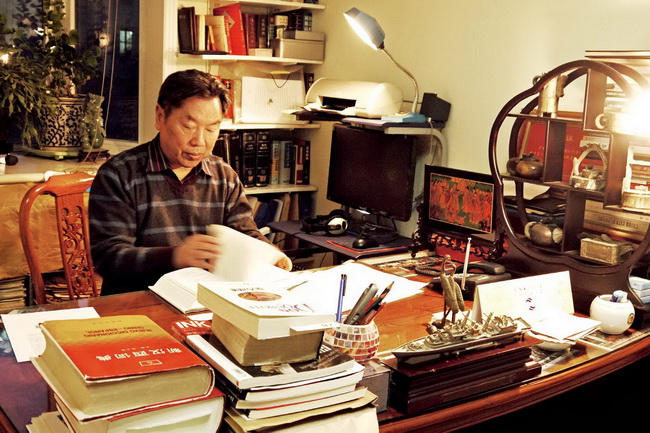

Yin Chengdong (1939- ) is a famous Chinese translator of Spanish literature. He is the main translator of the Chinese version of Gunter’s Winter and he is the vice-president of China’s Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Research Association. He once served as deputy general director and chief editor of the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau, and translated many of Gabriel García Márquez’s works, including his epic One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In April 2014, we sadly said goodbye to Gabriel García Márquez, who played a leading role in the Latin American Boom, a golden age for literature, poetry and criticism on the continent in the late 20th century. In June 2015, Juan Manuel Marcos’ Gunter’s Winter was published in China, marking a milestone in Spanish literary translation. Widely recognized as the best contemporary writer in Paraguay, Marcos’ name has become synonymous with post-Boom literature. Although the two Latin American writers have distinct styles, Marcos carries on Márquez’s legacy and has rung in a new era for Latin American literature.

So what is the appeal of Gunter’s Winter and other works of post-Boom literature? Why did the translator choose to translate this novel? Why has Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin’s concept of the polyphony of dialogue become the theoretical basis for understanding this novel? The translator of the Chinese version of Gunter’s Winter Yin Chengdong attempted to address these issues in an interview with CSST.

CSST: Could you please explain the value of translating Gunter’s Winter into Chinese?

Yin: Gunter’s Winter is less than 300,000 words, but it has rich content and a distinctive style. The author Marcos tactfully adopts multiple methods, e.g. flashback, intertextuality and stream of consciousness in the limited words. The novel reveals various ethnic groups and their society as well as prospects for life in Paraguay, a land that will seem remote and exotic to Chinese readers, from multiple levels and perspectives, manifesting people’s unyielding and heroic spirit against military tyranny. Marcos himself was a victim of Alfredo Stroessner’s autarchy. He was forced into exile and had to live abroad for more than 10 years. That’s why this novel is filled with a strong autobiographical color. He also skillfully applied Russian literary master Bakhtin’s theory on polyphony of dialogue and conducted a thorough and useful aesthetic exploration of the writing patterns of narrative literature. Since it was originally published in 1987, Gunter’s Winter has been reprinted several times, constantly revised and translated into more than 20 foreign languages in succession. The 2013 version is a unique annotated edition, which not only includes the novel but also adds commentary and an extended foreword by American expert on Paraguayan literature Tracy K. Lewis along with annotations, references and detailed indexes. It is the first time a Latin American novel has ever been published in such an annotated edition.

CSST: So it must have been very difficult to translate this novel into Chinese.

Yin: Yes, it was. Many chapters didn’t have any punctuation, so it was very difficult to translate. But those difficulties also inspired my curiosity, attracting me to probe into them, and ultimately I received great joy from them. Although the process of translation took time, the publisher encouraged and supported me greatly. And the novel has been published two months ahead of schedule.

CSST: Chinese readers would like to know more about this novel. Could you please explain more about its relation with Bakhtin’s theory on polyphony of dialogue?

Yin: Lewis indicated in the foreword that Bakhtin’s predictable theory provides a basis for understanding world-class novels in recent decades, including Gunter’s Winter. According to Bakhtin’s theory, after Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, a fundamental divergence appeared in Western literature. This divergence was characterized by an expansion in the functions of novel language. Novel language has changed. It formerly only used the single voice of a narrator or writer. Its functions have not just been limited to narration, but instead the novel is treated as an integral whole, a phenomenon with multiple writing styles, miscellaneous forms of language and many voices. Multiple forms of language and many voices are a distinct characteristic that distinguishes this novel from other literary genres in terms of how language is used. A novel’s rhetorical devices should completely develop the text’s multiple forms of language to connect all inner voices with each other. Then it will generate an artistic effect of polyphonic dialogue.

CSST: Although it contains many voices, multiple levels and perspectives, the novel should have a main framework. Is that right?

Yin: If we want to find out the story’s main framework in Gunter’s Winter, we may say it refers to that the author has relatively completely told the destiny of two families Quiroga and Sanabria in Corrientes, an allusion to Asuncion. On the basis of the main framework, there are several subplots in the novel that trace back the history of Paraguay, the experience of deportees who are sent into exile, young people’s love affairs and stories, and the military government’s autarchy and utter disregard for human life. It widely and deeply describes the social reality in Paraguay.

CSST: We see that there are many quotations in this novel. That is the application of intertextuality. The idea of intertextuality also falls under the scope of Bakhtin’s narrative theories: Do any narrative articles use an implicit or explicit means of connecting with other articles, such as mapping and citation, in order to realize the alignment between external voices and the original text’s voice?

Yin: Ancient Chinese poems also stress intertextuality. But it only refers to mutually supplementary words in one line, two adjacent lines or one poem combined together to express one complete meaning, which is a simple rhetorical device in the traditional sense and totally different from intertextuality in the post-modern context. The intertextuality of modern narrative art emphasizes texts’ inclusiveness and extensibility in terms of literary tradition. In this way, it will build up a dialogue between the novel and external texts. In Gunter’s Winter, Marcos controls each writing style derived from external texts very well and writes down old and new quotations freely and flawlessly. It fully expresses his profound and excellent intellectual accomplishment and artistic skill. Obviously, in Chinese readers’ eyes, intertextuality is the most important characteristic that differentiates this novel from other Western novels. At the same time, it also presents the most difficult obstacle for readers. Intertextuality makes Gunter’s Winter distinguished from many works of the Latin American Boom, and it is the key for Gunter’s Winter to turn into a model for post-Boom literature.

CSST: The Latin American Boom in the 1980s came as a surprise to many Chinese writers, including Nobel Prize laureate in Literature Mo Yan. Can novels be written in this way? So how will post-Boom literature inspire Chinese writers?

Yin: The reason why Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude was so well received was that both his grand themes and innovative writing techniques differentiate his works from those of any other Latin American author. Actually, the success of Gunter’s Winter can also be attributed to Marcos’ total writing innovation. For instance, when describing violent scenes, Marcos’ writing style is not only different from Miguel Ángel Asturias’ Mister President and Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch, but also discriminates from other Latin American works with themese of violence, such as Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat. Moreover, Gunter’s Winter describes a complicated and wonderful world of semantics, and this has never been shown in any other works. Macros utilizes Bakhtin’s theory on polyphony of dialogue and also develops the theory further with his understanding. So I think the biggest inspiration for Chinese writers who read works of Latin American post-Boom literature should be innovation. That means writers’ creations should be equipped with innovative spirit, should advance, develop and get rid of the effect and pattern of committed literature. Just like Macros indicates in the novel, “[Writers] should use paradox to train the mind instead of final conclusion.”

Wu He is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE