Chi du: Ming Dynasty correspondence illuminates history

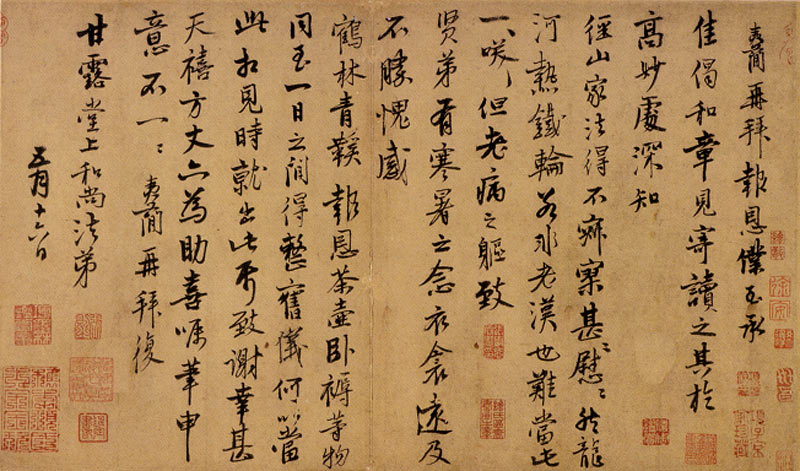

One piece of chi du from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Over the past two decades, studies into the lives of the literati of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) have accumulated lots of historical materials represented by collections of poems and literary works as well as chorography. However, chi du, or correspondence, is the most direct historical material when it comes to analyzing the lives of the literati in ancient China.

With extensive coverage and factual information, chi du exhibits the characters of literati in a unique way.

From chi du, people can find that most literati in the Ming Dynasty didn’t confine their interests to one field, rather they were versatile. For example, the great thinker Gu Yanwu in one piece of correspondence to the distinguished writer Gui Zhuang, acknowledging his reading of Gui’s two poems, commented that these poems were still of the tune of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and Gui should concentrate more on issues of that time.

One can also learn some historical facts in chi du that are not easily found in other materials. As for the act of giving remuneration to a writer, painter or calligrapher, it is usually not clearly stated in other historical materials. In one piece of correspondence by calligrapher and painter Dong Qichang to a client who invited Dong to write the preface for one piece of writing, Dong asked for another famous painter Wen Zhengming’s painting as remuneration. Dong’s words also reflect his straightforward character.

Correspondence with family members shows the affection these literati held for their loved ones. In one letter by official Sun Zhi to his son Sun Chengtai, the father applauded the son’s scholarly achievements and asked the son to tour Jinling (now Nanjing) where he was studying and pay visits to their friends and relatives in that city.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE