Writers, works considered equally when awarding Mao Dun prize

Lu Jiande

Chen Zhongyi

Tang Shan

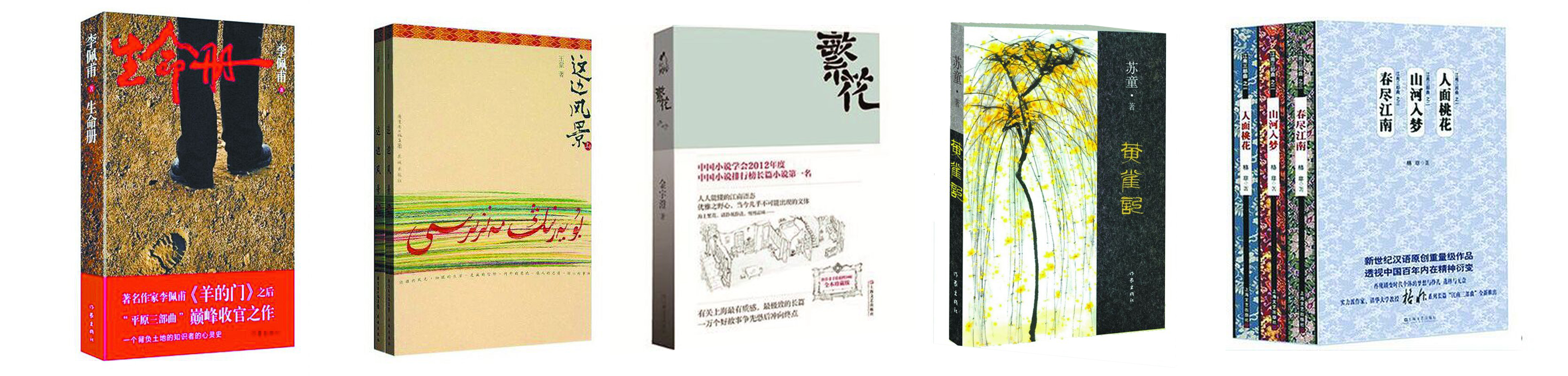

Five books that were awarded the ninth Mao Dun Literature Prize.

Lu Jiande is the director of the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and editor-in-chief of Literary Review.

Chen Zhongyi is the director of the Institute of Foreign Literature at CASS and a member of the Congress of China Writers Association.

Tang Shan is a book critic and the director of the Supplement Department of the Beijing Morning Post.

Every year, the Mao Dun Literature Prize, China’s top prize for modern literature, casts a spotlight on the works of the nations most beloved authors. Recently, Ge Fei’s Jiangnan Trilogy, Wang Meng’s Scenery in this Side, Li Peifu’s Book of Life, Jin Yucheng’s Flowers and Su Tong’s Siskin were awarded the ninth Mao Dun Literature Prize. On Sept. 29, the award ceremony was held in Beijing, attracting the most prominent figures in China’s literary circles.

Compared to the Nobel Prize in Literature and other venerable foreign literary prizes, the Mao Dun Literature Prize is a fairly recent tradition, which is still striving to establish its credibility. A CSST reporter interviewed Lu Jiande, Chen Zhongyi and Tang Shan on the rules for selection of the Mao Dun Literature Prize, the aesthetic orientation of prize-winning works and the status quo of Chinese literature.

CSST: Mr. Tang, as a book critic, have you ever read these five prize-winning works?

Tang: Yes, I have read all these five novels. Technically, they all are well written. After all, these novels are selected by so many professional judges. However, this generated a big problem, the popularity of “cumbersome realism.” This realism is much more complicated than the realism we learned at college, which is to say, this realism is not that realism. It always covers a story inside another and sets many characters and various angles of view. When we were at college, novels focused on details. But now most details are overshadowed by complicated stories and characters. I don’t know whether writers came up with such complex interlinked stories at home or if these stories did exist in real life. In short, very few can touch people’s hearts. I don’t think this is the real art.

Realism is a technique for novel writing, so many Chinese writers compare the stories which are the most complicated and deliberately highlight language skills. To be selected for the literary prize, writers are competing in terms of writing skill and who has the most characters, the most complex stories, the weirdest plots and the strangest local features. In short, the more complicated and trivial the novels are, the greater the chance is that they will be recognized. So I think this is completely competing with everything but literature. It is non-literature. The true literature is based on humans. It ought to be tender, spiritual.

CSST: The average age of this year’s Mao Dun Literature Prize winners is 61.8 and there are no writers under the age of 50. This has led to some criticism that the Mao Dun Literature Prize tends to evaluate writers instead of works. But some judges strongly support this argument, indicating that the Mao Dun Literature Prize should become a lifetime achievement award, of which 40 percent should be awarded to works and 60 percent should be awarded for writers’ reputation.

Lu: I don’t think it matters how old the prize-winners are. But the Mao Dun Literature Prize should be a novel prize and cannot become a lifetime achievement award. Otherwise, it’s not necessary to gather judges to evaluate which novels are better. Instead they can just rank those writers who have a higher reputation. Like the Man Booker Prize in the UK, it only focuses on the works. The judges just read novels and aren’t quite concerned about writers’ reputations.

Tang: From the perspective of foreign literary prizes, the Man Booker Prize in the English-speaking world is awarded to works and its prize-winners are very young, with an average age of 49. We all know that the Nobel Prize in Literature is a lifetime achievement award. The average age of its prize-winners is more than 70 and has almost reached 80 in recent years. But the Mao Dun Literature Prize is still wandering between them and is still on the road. The first rule of selection of the Mao Dun Literature Prize is to insist on the perfect combination of ideological content with artistry. But it’s so difficult to say there’s no bias in keeping the balance between them.

Of course, after all these years, the Mao Dun Literature Prize has constantly improved and clearly confirmed that this prize is a novel prize as well. But the problem is that we don’t have an effective mechanism to ensure its execution. So the current situation is admittedly relatively vague. It leads to such a result between a novel prize and a lifetime achievement award.

Chen: A strict novel prize is not impossible. It does exist. On the international stage, novel prizes mostly adopt anonymous review. Generally, the writer sends the manuscript to the prize-issuing organization, and its panel of judges selects the best works through blind appraisal. The panel eliminates a long list of candidates with a simple majority vote.

After two or several rounds of selection, the candidate with the most votes becomes the winner. However, the Mao Dun Literature Prize seems to take both works and writers into account, and it hasn’t yet formed a principle or consensus about which one is more important. I’m afraid that this is one of the prime reasons for the bias in the selection rules of the Mao Dun Literature Prize. I think that laying particular stress on either reputation or works will cause totally different results. So based on all previous Mao Dun Literature Prize winners and works, the scale between them has yet to be standardized and balanced. Emphasizing works serves to confirm the selection rules and avoid many unnecessary misunderstandings and rumors.

CSST: Through the Mao Dun Literature Prize, how do you assess the current situation of Chinese novels? Do you agree with the statement that “literature should endow people with a warm strength?”

Lu: Some Chinese novels show readers a lack of humanity, which neither nourishes people nor inspires passion for life. For literary works, I think that we should look at what these works describe—whether they’re worthy of the public’s close attention. And then we must ask how they awake all the echoes in our heart or how their presentation of a struggling soul will profoundly enlighten us. But now, some novels cannot leave any traces in our memories.

In my opinion, the depiction of society that flows from the pens of Chinese writers is unlovely and very rough. They cannot explore something that touches our feelings or nourish our inner hearts. Their novels, including some prize-winning novels, are filled with craven characters. Some writers are immersed in describing the world’s absurdness and madness. This should not be the focus, as it is not the mainstream, not is it pursued by the majority. Some Chinese writers are not capable of depicting characters with a lasting strength. Lu Xun (1881-1936) once said that Chinese literature lacks honesty and love. Our works are full of ferocious and disgusting depictions but are short of the goodness in the ordinary life.

I hope Chinese literature could be more positive. The best literary work is a sublimation of life. Hopefully, Chinese writers can put more efforts in this field to explore more new writers. It’s not necessary to always depict characters as important persons or make their works the bestsellers. The work I’m looking forward to is the one that can sketch a rich inner world with a warm strength across cultures, regions and time.

Wu He is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE