Personal narration: Minor details reflect wider society

Viewing large things from small details

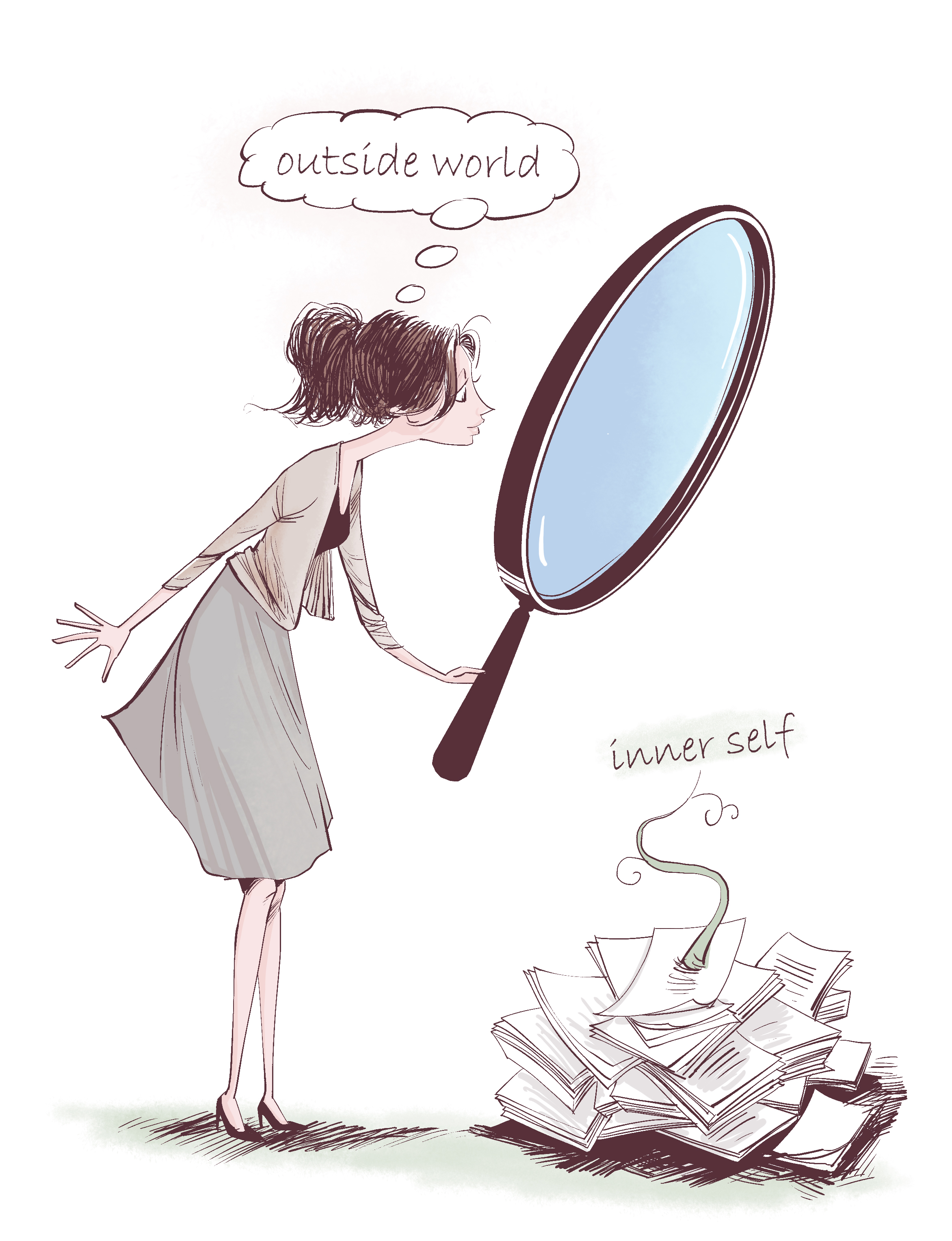

Cartoon by Gou Ben; Poem by Long Yuan

Peering through a magnifying lens,

A woman’s view of the world transcends

What can be seen through careful observation,

With both the internal and external under reflection.

If she misses both “big”and “small” she fails,

To truly see large things from small details.

Delicate feelings and sentiments are not mere distraction,

And marginalized narration holds its attraction.

In presenting the voices of the “ordinaries,”

Ru Zhijuan’s Housework respects the “nobodies.”

For literary comments to not be forsaken,

Remember Lu Xun’s plea to awaken.

Even today there still exists a strange phenomenon within the field of female literary review—works about the family, spouse, friends and women themselves, with the so-called limited, narrow, superficial subjects, were considered confined to the “small world” with the backwardness of the petty bourgeois. In fact, female authors do not only write about important topics, but also about ordinary people, and tend to describe big things through small details. Chinese writer Ru Zhijuan’s Housework is one example. As Lu Xun once puts it: “The awakening of human beings lies in that of the individuals, especially that of women, children and peasants. Otherwise, the evolution of mankind would not preclude them from withering away.”

In the early 1990s, the narrative style of writers like Lin Bai and Chen Ran was often labeled pP

The term “personal narration,” was, in fact, connected with the debate among writers in the 1980s—the debate between the “small world” and the “big world.” These refer to concepts proposed by Zhang Kangkang, a famous contemporary Chinese writer, at an international female writers’ conference hosted in 1985 in West Berlin. She raised the “two worlds” of writing, calling upon writers to “fairly depict and reveal both the external and internal worlds that women are facing.” What ensued was the more explicit distinction of the two worlds. As some writers put it, the vision of female writers should be concerned both with the “small world” of their inner selves, and the “big world” of social life. Female writers should reflect their inner world through the consciousness of being “female,” and the outside world through the consciousness of being “human.”

Two worlds converge

The debate, unconsciously, has brought people’s attention to a weird phenomenon within the field of female literature. Among the commentaries on Chinese modern writers Bing Xin, Lu Yin, Ding Ling, and Xiao Hong in the middle of the last century, the divide between the “small world” and “big world” was mentioned. Works about the family, spouse, friends and themselves, with their so-called limited, narrow, superficial subjects, were considered confined to the “small world” with the backwardness of the petty bourgeois, but works that stressed revolutionary social movements were considered reflective of the “big world” as representative of advanced proletariat literature. This dichotomy ran throughout literary criticism during the era of the League of Left-Wing Writers, the Yan’an Period (when the Communist Party of China was based in Yan’an, Shaanxi Province), the thirty years after the founding of People’s Republic of China, and also the mid-1980s. “Small” means “narrow,” and “big” means “grand”—that is what defines the differentiation between “grand narration” and “marginalized narration.” Thus, works that emphasize women themselves would be debased as incongruous. Also, the mention of female writers or feminists were obstinately and partially associated with parochial words like “small world,” “sex” and “body,” which distanced them from public life, social ideology, and collective actions.

Undoubtedly, such distinctions between the “small world” and the “big world,” as a result of the long-term opposition between “individuals” and “politics,” was the inevitable product of the binary, opposite way of thinking, which had a great impact on the debate on women’s literature in the 1990s. The works of Lin Bai and Chen Ran, thus, were labeled “personal narration” and became the epitome of the women’s “small world”—which not only alienated them from ideology, but also estranged them from group experiences. But the fact is, the personalization of female literary narration is part of a strong group experience and may have a political nature.

‘Your ideas can’t be yours alone’

Women’s literature itself actually describes the “big world.” By telling personal stories from the perspective of a particular group in society, they also manifest females’ wakening awareness and growing perception of their bodies, as a collective voice that called for an escape from the restrictions of gender and the return to the public sphere exclusive to women. What it evinces is the more complete and unified image of females.

In many of her works, Lin Bai depicts the miserable experience common to the female group: “Being pregnant makes a woman anxious. It is unknown to them whether the baby will be a boy or a girl, and whether there will be anything innately wrong with the baby…anxiety makes a woman weary-looking with a lifeless face, and anxiety makes them feel like vomiting…it is a kind of sharp pain that is ten times more acute than that brought by knife-cutting, which, would never be felt by those without such experience…such pain makes even a second eternal and five minutes fifty years.” “It skims over the body of each woman, but never touches any one of the men.”

The British novelist Doris Lessing, in the preface of The Golden Notebook, explicitly points out that we don’t have to be vexed when writing about our own trivialities. Those so called unique and incredible experiences are actually shared by the masses. “Writing about oneself, one is writing about others, since your problems, pains, pleasures and emotions—and your extraordinary and remarkable ideas—can’t be yours alone.”

Daily chores mirror ideology

Indeed, to detect “the big” through “the small”, even if they are merely about women’s personal special experiences and feelings, is not necessarily personal. The personal narration usually represents the polybasic yearnings of the female group. As the frequently heard feminist rallying cry states: “The personal is political.” For females, as individuals, their daily behaviors are closely interconnected with political ideology and economic structures. Writers like Tennessee Williams and Terry Eagleton also reveal the relationship between daily life and political ideology in their works. To them, daily experiences including those in the aesthetic spheres of literature, film, music, dancing, and painting all bear political traits, which could be seen as particular aspects of life that mirror ideology.

These ways of thinking could also be found in the book The Sublime Figure of History: Aesthetics and Politics in Twentieth-Century China authored by Wang Ban, a professor from the Department of East Asian Languages and Comparative Literature at Stanford University. Professor Wang’s analysis seems to have been simplified to the sublimation of political activity into aesthetic forms, but the examination between aesthetic manifestations and ideologies as well as politics deserves attention. Professor Wang considers politics, as a collective identity, to be rooted and functioning in the individual’s brain, emotion, taste, and other sectors of the internal world, and to be intrinsically in specific perceptual modes and symbolic activities. Taking novels of Chinese writers Zhang Ailing, Can Xue and Yu Hua as examples (especially Yu Hua’s On April 3), Professor Wang makes a tentative effort in his book to illustrate that petty personal trifles are tightly interrelated with mainstream ideology. This provides a new perspective to study the interconnectivity between literature and politics, as well as individuals and groups.

Though literary creation, as an individual behavior, in essence, is one way that the subject of writing participates in the mobility of society, and the subject, by itself, is isolated and discrete from others, its behaviors take place in the intersection between ideological, political, aesthetical, and ethical discourses. As such it conveys information about the community. As the Chinese writer Chen Huangmei puts it, the world, era, society, and human beings that female writers delineate are those with their own, unique visions.

The Chinese literary critic Li Ziyun also said that female authors do not only write about important topics, but also about ordinary people, and tend to describe big things through small details. As a result, significant issues such as ideology can be seen through the lens of the most ordinary people. For instance, another Chinese writer Ru Zhijuan’s Housework, in presenting the sufferings of ordinary people, calls for respect for each person. The famous Chinese contemporary writer Zhang Kangkang also posits that the feminine style and charisma in women’s writings come out naturally since they are decided by the psychological and physiological characteristics of women, which, do not need to be deliberately pursued. To Wang Anyi, also an eminent Chinese writer, when women are trying to display the era they are in and the politics they perceive through works, they will always connect such depictions with their quite small but weighty feelings. Lin Bai also considers her work to have strong personal notes, but when talking about laid-off female workers or other common issues affecting women in society, she also emphasizes that such experiences, in some senses, overlap with her own life.

Lin Shuming is from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Guizhou Normal University.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE