'An epoch of developing equal conversations has begun'

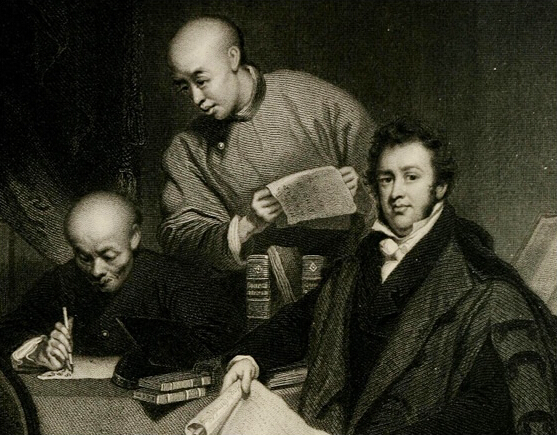

Robert Morrison (1782-1834) was the first Christian Protestant missionary in China and the first to translate the whole Bible into Chinese.

Zhang Xiping (1948- ) is a professor and doctorate supervisor of Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU), dean of the International Institute of Chinese Studies at BFSU, and chief editor for both International Sinology and International Chinese Language Teaching and Learning. His research interests range from history of Chinese and Western cultural exchanges in the Ming and Qing dynasties to history of Western Sinology. He has authored The Past and Present of European and American Sinology.

At present, there are two extreme attitudes toward overseas Sinology in China. One completely negates the research of Western Sinologists and uses the label “Sinologism” to refer to the domestic study of overseas Sinology. The other entirely follows the studies of Western Sinologists while uncritically accepting their research achievements. However, Zhang Xiping indicated that these two attitudes each have their own biases. He talked with a CSST reporter about his critical perspective on overseas Sinology.

CSST: Sinologists from various countries have different aims when studying Chinese culture. Chinese culture has often suffered from deconstruction because of the need for research subjects. The fundamental aim of early European Sinology was proselytizing in China, and American Chinese studies were designed to serve America’s Asia-Pacific regional strategy. Do you think this fundamentally decides that we should hold a critical attitude toward overseas Sinology?

Zhang: Although Sinologists from various countries have their own cultural features when it comes to explanations and understanding of knowledge, the knowledge itself is a paraphrasing and record of Chinese history and culture. For this part, Chinese scholars should take the responsibility to recognize their shortcomings as well as contributions. Generally speaking, the work of Sinologists is a significant reason why Chinese culture has exerted an influence on various countries in the world.

We should understand the development of Sinology in each country and promote active exchanges among Sinologists in different countries. We cannot mechanically apply postcolonial theory and politicize all the studies of Western Sinologists. Quite a few Sinologists, such as Richard Wilhelm (1873-1930), had a very serious academic approach to study China.

But at the same time, the problem you mentioned indeed exists. I will use missionary Sinology as an example. Because of the changing times, the relationship between Chinese and Western cultures in 1500-1800 differed from that after the 19th century, and Western missionary Sinology also showed different features at that time.

Whether one is speaking of the Catholic missionaries who came to China earlier or Protestant missionaries who came to China later, they share two things in common. They had the same Christian religious motivations, so “the Christian Occupation of China” was their common goal. Second, their works all indicated a cultural stance of “Western-centrism.” So we cannot avoid these two things and should explain them from cultural and academic perspectives. This will enable us to better understand missionary Sinology’s features and the problems that arise when translating Chinese classics.

CSST: The key is that we should keep a strong cultural self-consciousness and academic awareness.

Zhang: I think that cultural self-consciousness and academic awareness are the basic starting point where we develop studies on overseas Sinology and the history of Western Sinology. The opening and comprehensive cultural spirit is our basic attitude toward overseas Sinologists. A critical spirit for seeking truth and a cross-cultural perspective constitute the basic academic position from which we should examine Western Sinology.

Still looking at missionary Sinology as an example: Missionary Sinology was born from the historical process of Chinese and Western cultural exchanges in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1616-1911) dynasties. In general, Western missionaries in China worked in two areas: One was to bring Western culture into China and the other was to introduce China to the West. But those seminars led by overseas academic institutes of the church mainly focused on studies of “the Eastward Spread of Western Learning (a late Qing Dynasty term for Western natural and social sciences),” which is to say studies of the history of the Christian church in China.

Studies in this field should definitely be improved, but Western missionaries have been comparatively weak in terms of the introduction and study of Chinese culture, i.e. the Western spread of Chinese knowledge, which implies their “Western-centrism.”

In fact, many scholars think that China had a deeper influence on the West in the process of Chinese and Western cultural exchanges in the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty. The book La Chine et la Formation de l’Esprit Philosophique en France (1640-1740) reflects French scholar Virgile Pinot’s deep thoughts. It tells us that Europe utilized Chinese ideas to successfully overcome the constraints of medieval thought.

In other words, Europe at the time, especially France, reflected upon their own ideas by discussing Chinese thought and philosophy. This indicates that exchanges between Chinese and European cultures have traditionally followed a pattern of interaction rather than being a one-way transmission from the West. We should examine the evolution of Chinese and Western thought together under the same historical background.

CSST: Some domestic scholars think that because research principal part of Sinology are foreigners, it essentially means that Sinology falls under the purview of Western learning. The effects of Sinology being systematically imported to China on a large scale even surpassed those of mainstream Western learning because foreign Sinology may directly affect and break up the self-understanding of the original civilized community. This will easily make us subject to the problematic formulations of others. Trapped by the boundaries of discourse set by the West, we lose control. So what do you think of this?

Zhang: I agree with you. We should not only correct the biases of Western Sinologists and the gaps in their knowledge, but also the more important thing is to help our scholars come out from under the shadow of Western Sinology, to avoid submission to their research paradigms and to reestablish the Chinese academic narrative.

China is a latecomer to modernization, and the development process of its history and culture after the late Qing Dynasty was forcibly stymied by Western invaders. After the abolition of the imperial examination in 1905, the traditional Chinese academic narrative began to face enormous crises. With the introduction of Western learning and establishment of new schools, the meeting of traditional Chinese knowledge and Western learning placed the traditional Chinese academic narrative at a disadvantage.

At the same time, Western Sinology came into Chinese scholars’ field of view along with the introduction of Western learning. China finally accepted Western learning because they accepted the model of Western Sinology studies. As a foreign form of knowledge, Western learning is just an instrument. But only when it is applied to domestic cultural analysis can Western learning gradually permeate from the external to the internal. As it were, the transition from the external to the internal is accomplished by the assistance of Western Sinology.

The birth of modern Guoxue, the academic study of traditional Chinese cultures, has an inherent correlation with Western Sinology. But we also need to realize that mechanically applying Western knowledge systems to explain Chinese culture and history is obviously wrong.

CSST: Getting rid of Western Centrism’s cultural narrative and reestablishing modern Chinese academics constitutes a broaden topic. So could you please introduce how we could conduct a conversation with Western Sinology?

Zhang: In recent years, the circle of American Sinology has often adopted approaches of postmodern history to study Chinese history and culture, and the theoretical framework of their studies is hard to integrate into Chinese historical materials.

When Western Sinologists understand and study Chinese history and culture, they are always easily affected by Western knowledge systems and barely realize the big differences between the form of China’s civilization and development history and that of Europe and the US. Certainly, it is very natural that Western Sinology differs from ours.

First of all, we should realize that the existence of overseas Sinology marks that China’s knowledge has already spread all around the world, which is indicative of China’s cultural influence. In this light, we should thank these Sinologists because their studies help the world to learn more about China.

Furthermore, the more important thing is that we should develop conversations with Sinologists across the barriers of culture in order to understand this overseas knowledge. We need to conduct a series of dialogues and criticism on the academic level. An epoch of developing equal conversations has begun.

Mao Li is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE