Plot historically held central place in Peking opera criticism

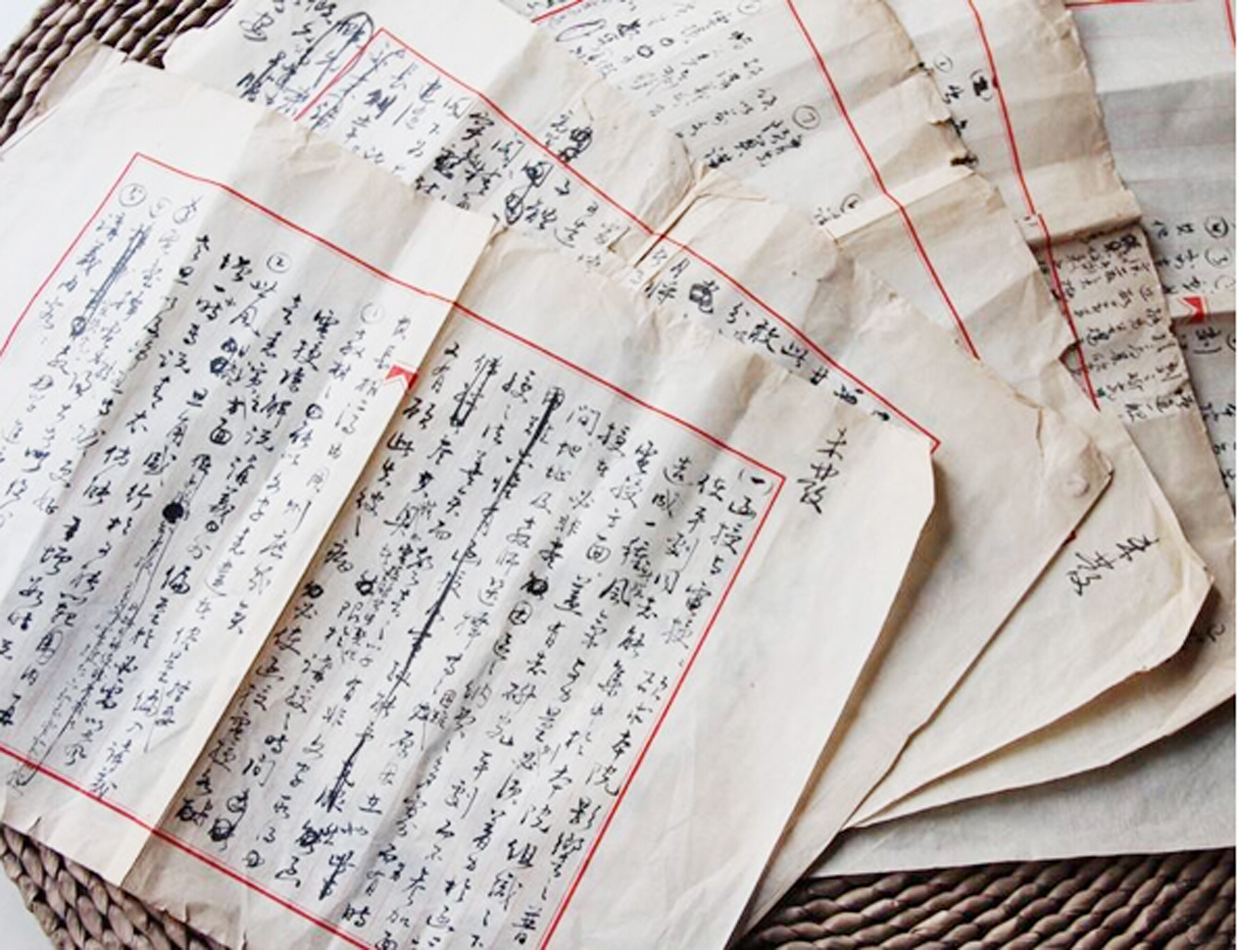

Su Shaoqing’s manuscripts show his critical thoughts on Peking opera during the Republican period.

From the perspective of developmental social history, traditional Chinese opera performers have long been considered of only minor importance. Their jobs were seen as menial, affording them little status in society. This view has shaped literary studies of Chinese opera and Qu, a type of song verse that became popular in the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368), placing the emphasis on opera texts and librettos instead of the performance of individual actors or actresses.

Moreover, texts and librettos can be handed down through written records, while the remarks of critics were insufficient to fully capture the essence of opera performances that predated the invention of modern audio and video technology. The ignorance of performance art and paucity of historical records about opera performance have led to a dearth of theoretical studies on the history of traditional Chinese opera.

Opera criticism in the Yuan, Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1616-1911) dynasties involved many comments on the performances of players. However, these comments, bound by the limits of history, are relatively scattered, random and lack theoretical conclusions. Although the Yuan Dynasty saw the publication of some significant works on opera criticism, like the Theory of Singing, these works focused on singing while neglecting other elements of the art form. During the Republican period (1912-49), the main difference between conclusions and summaries of the artistic regularity of traditional Chinese opera performance and those in the past is that the previous ones embraced the insight of studies of drama.

In this period, many artistic commentaries focused on Peking opera but offered a reference and guidance for other forms of opera as well. The typical example is the issue of singing. Of the four areas of performance in Peking opera—singing, speaking, acting and acrobatic fighting—singing always comes first. Pronunciation is considered the most important aspect of singing ability. Many articles on the articulation of songs in this period discussed these issues.

Although Peking opera performers had a wide degree of latitude in how the songs were sung, the operas were required to conform to the details and plots. For this issue, the famous dramatic critic Su Shaoqing (1890-1971), who published a number of critical articles on Peking opera during the Republican period, divided the songs into four steps: intro, development, change and conclusion. In his youth, Su Shaoqing learned how to sing Peking opera from many great masters and he was intimately familiar with performance details of a variety of Peking operas.

He argued that regardless of how performers vary the tunes through these four steps, their purpose is to present dramatic plots instead of showing off their singing skill. This opinion won him a reputation in the circle of Peking opera. It demonstrates that at least 80 years ago Su's conclusion became a consensus for Peking opera-goers.

In the 1920s-1930s, scholars paid attention to traditional Chinese operas, such as Peking opera and Kunqu opera. Their comments on Peking opera performers' pronunciation, tune, posture or action reflect a meticulous and nuanced observation and experience. The ultimate purpose of their criticism was for the art of Peking opera to rapidly achieve standardization in every aspect and conform to its dramatic characteristic by following dramatic plots. During this period, the highest evaluation criterion for performance art was standardization. However, the conformity of actors and actresses to this criterion did not necessarily mean they were good performers. But artists who could not follow this criterion would be subjected to severe criticism, even if they were masters of the art form, such as Tan Xinpei (1847-1917), Yang Xiaolou (1878-1938) or Mei Lanfang (1894-1961).

Zhang Yifan is from the Research Center of Chinese Opera at Renmin University of China.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE