Marxism crucial to evolution of Indian historical research

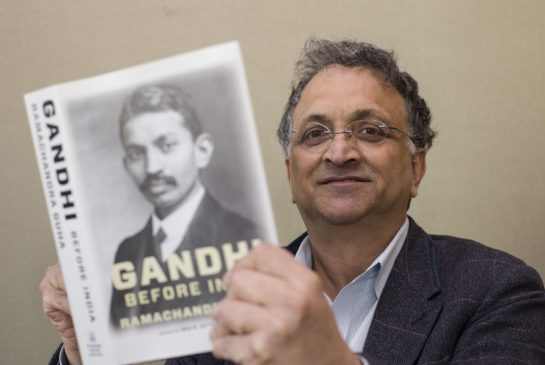

Ramachandra Guha, a historian and biographer in India

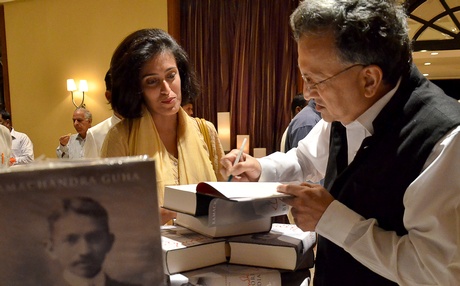

Ramachandra Guha autographs his book Gandhi Before India for a fan.

Ramachandra Guha (1958- ) is a historian and biographer based in Bangalore. He has taught at Yale University, Stanford University, the University of Oslo and the Indian Institute of Science. He has also served as a professor of history and international affairs at the London School of Economics. His representative books include The Unquiet Woods, Savaging the Civilized, This Fissured Land: An Ecological History of India, Makers of Modern Asia, Gandhi Before India and India After Gandhi.

At the end of the 19th century, Marxism first gained currency in India. The introduction of the Marxist worldview had a tremendous impact on revolutionary struggle and ultimately exerted an influence on Indian historical research. Recently, a CSST reporter sat down with Ramachandra Guha to discuss how Indian historical research has developed over time and how it has been influenced by Marxism.

CSST: As a historian, how did you recognize the impact Marxism has had on Indian historical research?

Guha: It was closely connected with my experience. In October 1984, I got my first academic job at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences in Kolkata (then Calcutta). A week after I joined, a friend from Chennai (then Madras) sent me a petition on the plight of the Tamils in Sri Lanka, which he hoped some of my colleagues would sign. The first person I asked was a senior historian of Northeast India, a person whose work I was familiar with but with whom I had not yet spoken. He read the petition and said, “As Marxists, the question you and I should be asking is whether taking up ethnic issues would draw attention away from the ongoing class struggle in Sri Lanka.”

My colleague was known to be a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Yet I was struck by the way in which he took it for granted that I must be a party man too. Although this was our first meeting, he immediately assumed that any new entrant to the centre must, like him and almost all the other members of the faculty, be a Marxist as well.

CSST: With the transmission and development of Marxism in India, Marxism has had a great influence on research institutes of humanities and social sciences in India, especially on historical research. So what do you think the reason for this is?

Guha: In the 1980s, Marxism occupied a dominant place in the best institutes of historical research in India. There were three reasons for this.

One was intellectual: the fact that Marxism had challenged the conventional emphasis on kings, empires and wars by writing well-researched histories of peasants and workers instead. The writing of Indian history was shaped by British exemplars, among them such great names as E.P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm, Marxist pioneers of what was known as “history from below.”

The second reason for Marxism’s pre-eminence was ideological. In the 1960s and 1970s, anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa were led by Communist parties. To be a Marxist while the Cold War raged, therefore, was to be seen as identifying with poor and oppressed people everywhere.

The third reason why there were so many Marxist historians in India was that they had access to state patronage. In 1969, the Congress split and was reduced to a minority in the Lok Sabha. To continue in office, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sought and received the support of MPs of the Communist Party of India. At the same time, several former Communists joined the Congress and were rewarded with cabinet positions. Now the ruling party began leaning strongly to the left in economic policy—as in the nationalization of banks, mines and oil companies—and in foreign policy, as in India’s “Treaty of Friendship” with the Soviet Union.

In 1969, before the Congress and Ms. Gandhi had turned so sharply to the left, the government of India had established the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR). The ICSSR was meant to promote research on the profound social and economic transformations taking place in the country. The council funded some first-rate institutions, such as the Institute of Economic Growth in Delhi, the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics in Pune and the Centre for Development Studies in Trivandrum.

CSST: In recent years, what changes has Indian historical research experienced under the influence of Marxism?

Guha: In 1972, the government established an Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) to promote historical research in India. But the control of Marxists over the ICHR weakened slightly in the 1980s and was then re-established when Arjun Singh became education minister in 1991. He was persuaded that the Ramjanmabhoomi campaign could best be opposed by the state sponsorship of “secular” and “scientific” history. Marxist historians flocked to his call, accepting projects and appointments with the minister’s favor.

CSST: How is the ICHR doing these days? What kind of effect does Marxism have on it?

Guha: Recently, Y. Sudershan Rao was appointed as chairman of the ICHR. People described Professor Rao as a “non-descript scholar who does not have any academic or intellectual pretensions,” but was known to be close to Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. They added that despite his ideological bias and lack of scholarly distinction, he was an amiable and friendly man.

His personal charm notwithstanding, Professor Rao has not published a major book nor a single scholarly essay in a professional journal. However, he has made known his belief in the essential goodness of the caste system as well as the essential historicity of the Ramayan and the Mahabharat. These may be among the reasons why he has been appointed chairman of the ICHR.

The Marxists who once ran the ICHR were partisan and nepotistic but also professionally competent. They thought Karl Marx—as distinct from the practice of Communist parties—provides a distinct analytical framework for understanding how human societies change and evolve. So their influence in the ICHR occupies the leading position.

Marxist historiography is a legitimate model of intellectual enquiry, albeit one that—with its insistence on materialist explanations—is of limited use when examining the role of culture and ideas, the influence of nature and natural processes, and the exercise of power and authority.

CSST: In the view of many Westerners, religion is the symbol of India and religious culture is so integrated into the lives of Indians that some believe there are few serious historians in India, a country filled with so many deities. But in fact, there are many excellent and distinct Indian historians who have made a great contribution to Indian historical research. Could you please recommend some to our Chinese readers?

Guha: Contrary to what is sometimes claimed by the West, there are many fine historians in India. From my own generation of scholars, I can strongly recommend to Chinese scholars the work of Upinder Singh on ancient India, of Nayanjot Lahiri on the history of archaeology, of Vijaya Ramaswamy on the bhakti movement, of Sanjay Subrahmanyam on the early history of European expansion, of Chetan Singh on the decline of the Mughal State, of Sumit Guha on the social history of Western India, of Seema Alavi on the social history of medicine, of Niraja Gopal Jayal on the history of citizenship, of Tirthankar Roy on the economic consequences of colonialism, of Mahesh Rangarajan on the history of forests and wildlife, and of A.R. Venkatachalapathy on South Indian cultural history. These historians have conducted excellent and highly effective research in their fields.

They have all read Karl Marx and digested his ideas. At the same time, they are not limited or constrained by his approach.They have been inspired by other thinkers and other models in their reconstructions of human life and social behavior.

Like their counterparts outside India, these scholars bring to the writing of history both primary research and the analytical insights of cognate disciplines, such as anthropology, political theory and linguistics. Their personal or political ideology is secondary (if not irrelevant) to their work, the robustness of which rests rather on depth of research and subtlety of argument.

Hou Li is a reporter from Chinese Social Sciences Today.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE