Museums played vital role in forging national identity

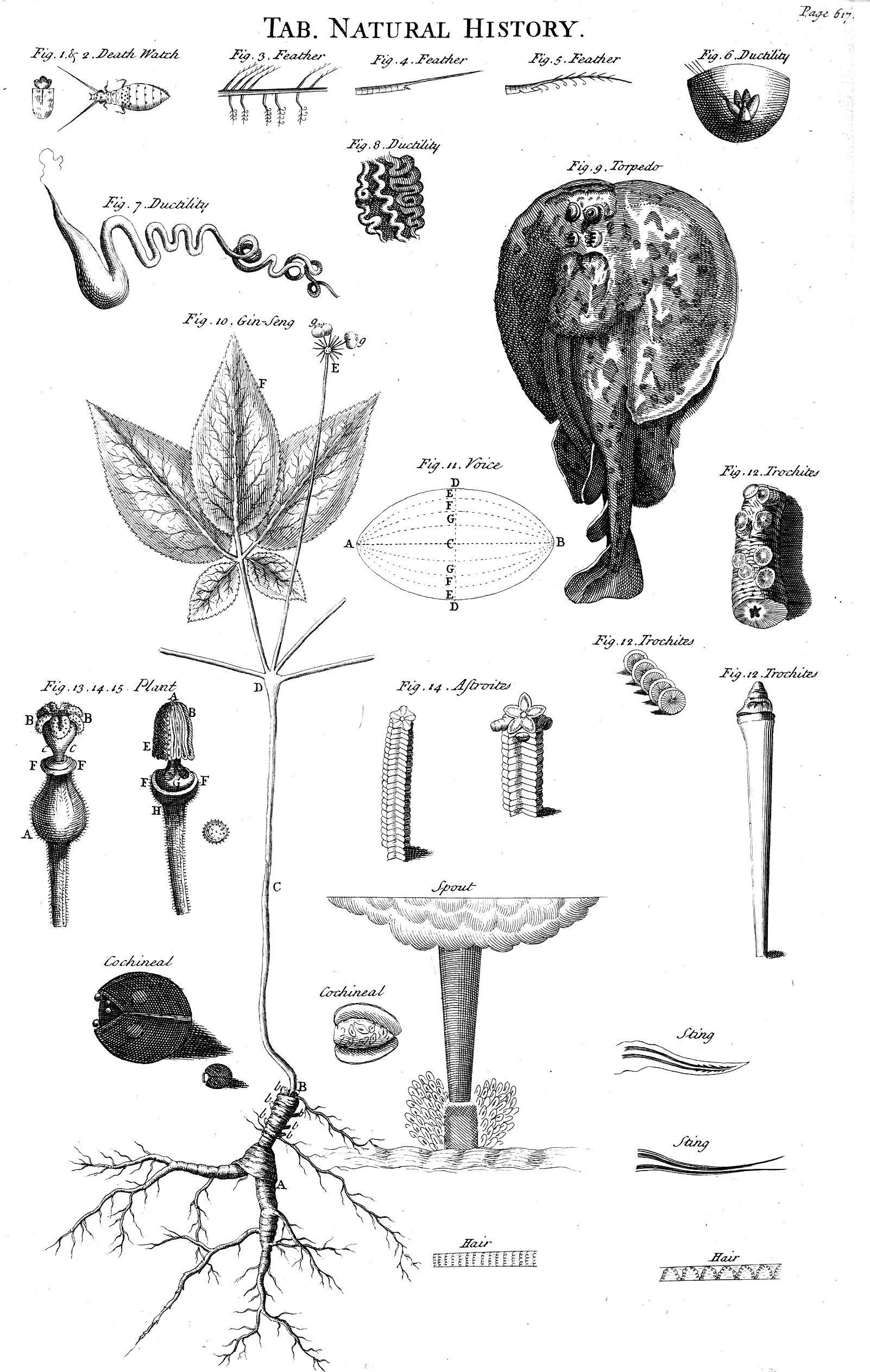

Tables of natural history from Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia

Nantong Museum was the first Chinese public museum established in 1905 by Zhang Jian, an industrialist and politician in modern China.

In the 19th century, natural history went through a process of reorganization. The location of exhibitions has changed from private collections to public space, which means that natural history, once studied as an individual hobby, has developed to the form of museum exhibitions, a service for all of society. And it was in the context of the emergence of modern nation-states that this transition occurred.

The transition, however, has varied from country to country in modern times. The “mother countries” of colonial empires, such as Britain and France, were the first to set up famous imperial museums, where the material objects collected by the governments or the common people were displayed. The British Museum and the Louvre are two examples of museums meant to demonstrate the historical and cultural glory of the empires.

In Southeast Asia and other colonial regions, the rise of local nationalism prompted the creation of pavilions for exhibitions and other collected works. Regarded as a representation of a country’s historical significance, they were taken into consideration within the strategic planning of a country.

Museums in China were initially established in the late 19th century and the early 20th century as an important bulwark of the country’s national education and identity.

Interaction with the West

“Learn extensively, inquire thoroughly, ponder prudently, discriminate clearly and practice devotedly.” This famous saying of China’s late Warring States Period (770-221BC) emphasizes the thirst for knowledge as a priority in the daily lives of Chinese people, stressing the need to know about the external material world.

Epigraphy, the study of inscriptions, has long been one of the most important spheres of study for Chinese scholars. The royal courts of each dynasty believed it was important to collect cultural relics and books.

Take the Song Dynasty as an example. At the time, the court employed masters of epigraphy, such as Lü Dalin and Zhao Mingcheng. It also set up storehouses, such as Jigu, Bogu and Shanggu, exclusively for storing cultural relics. Books such as the Xuanhe Collection of Artifacts and Xuanhe Collection of Paintings were compiled.

The Qing Dynasty marked a high point for the collection of antiques in China, and the Emperor Qianlong was especially fond of it. In addition to traditional books, paintings and other treasures, he was particularly interested in collecting Western clocks and watches. This was evidence of the cultural interaction between the East and West in the field of natural history.

The Western tradition of natural history also has a long past. As early as the time of Alexander the Great, the treasures obtained through expeditions were sometimes presented as gifts to his teacher Aristotle. The Western exploration of other continents and the advancement of colonial expansion further popularized antique collection.

At that time, a number of collectors and relevant organizations sprung up in Italy, Spain, Portugal, France and Britain. Hordes of antiques were amassed, forming the basis for future collections of famous museums.

The late Qing Dynasty was a time of great synergy between the traditions of Chinese and Western natural history. As the West expanded its colonial power eastward, close ties were established between the East and the West via the commercial partnerships in Guangzhou and other trading ports, and there was greater cooperation between collectors, scholars and relevant scientific institutions.

In this way, a global network of antique collection was formed. The Chinese tradition of natural history, by intersecting with and drawing upon the Western tradition in its modern form, became part of the mainstream of natural science.

A careful observation of the evolutionary process of Western natural history reveals that the apex of the discipline coincided with the time span of Western colonial expansion. The Eastern natural history, in some sense, is a type of Oriental study with Western natural knowledge as the research object. It helped shape the knowledge structure of natural science in colonies of that period, such as Asia, Africa and Latin America so that a global network of the knowledge and commodity trade was created.

Antiques, symbols of political power

In the process of institutionalization of natural history, European imperial power, which contributed to the formation of nation-states, became the biggest supporter and benefactor of the discipline. In his book Ways of Knowing: A New History of Science, Technology and Medicine, John Pickstone, a scholar of scientific history, observed that the biggest investors in museums were the nation-states in the 19th century.

Museums were built in capitals as symbols of national strength and royal power. In the book, France is used as an example. After the French revolution, the Ancient Royal Garden was developed into the Museum of Natural History. In the time of Napoleon, the antiques looted from Europe and North Africa, were considered symbols of the glorious French Empire.

Not only did the collections represent France’s power but also they enabled France to become the embodiment of science and civilization, because they were said to be the combination of natural order and great art, writes Pickstone in his book. This means that antique collection, which was more a practice of royal families, had been imbued with cultural civilization and historical significance by the power container—nation-states. As a result, they became important markers of a nation-state’s history and imagined reality.

The British scholar Benedict Anderson once said that a museum and the sense of imagination it engenders have profound political meaning. When European nobles and scholars displayed the array of antiques collected individually outside the palace or in other larger permanent venues, the audiences for the exhibition were expanded beyond their colleagues and friends to include the general public. When people from all over the country all focus their eyes on the same object and read its history, a collective national imagination gradually comes into being.

Evolution of museums

The first Chinese public museum established was the Nantong Museum set up in 1905 by Zhang Jian, an industrialist and politician in modern China. Though it mainly consisted of an ancient Chinese garden and a storage house for antiques, it embodied elements of both the local Chinese tradition and modern Western concept of museums.

Zhang Jian proposed to establish libraries, museums and other public facilities to further enhance the cultural awareness and understanding of state affairs. He also suggested to the Viceroy of Liangjiang (Jiang Su and Jiang Xi provinces) Zhang Zhidong, who was named as one of the “Four Famous Officials of the Late Qing”, that a museum was needed in Beijing to promote the cultural progress and national identity of the populace.

Though the proposal directly referred to the Japanese experience, he had also learned from the experience of the Louvre and the French National Museum of Natural History, which aimed to shift the focus away from a reverence for royalty and toward the construction of a national identity.

After the establishment of the Republic of China (1912-1949), the Ministry of Education set up the National Museum of Chinese History (part of Today’s National Museum of China) at the old site of the Imperial Central School. In 1926, it was relocated to the Forbidden City, where the Palace Museum was established a year earlier. This meant that the imperial tradition of Chinese natural history was transitioning to one characterized by the modern tradition of national identity.

At the same time, some other modern disciplines that derived fro m natural history were introduced to China. A large number of specialists and research institutes emerged. With their efforts, the shortage of modern Chinese scientific knowledge was overcome, heightening the national identity of the country in terms of knowledge.

This was not accomplished with one stroke but by increments. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Academia Sinica, and other research institutions began conducting field investigations in the border areas of China, but the nationalization of scientific knowledge still had a long way to go.

To summarize, the study of natural history, which was once a personal hobby, over time, was institutionalized in the form of museums, which serve as the role of a medium for boosting national education and strengthening national identity.

This evolution from individual to institution, from self-interest to national action, precisely reflects how a nation-state inherits from its tradition of natural history. And today’s rediscovery of the discipline enables us to once again turn our eyes to the value of individuals’ daily behaviors in the macro context of a nation-state.

Yuan Jian is from the Research Center of World Ethnology and Anthropology at the Minzu University of China.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE