Evolution of urban management in ancient China

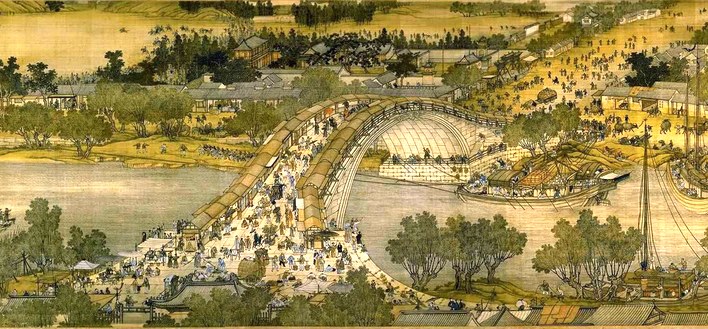

The painting “Along the River during Qingming Festival,” attributed to Song Dynasty artist Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145), provides insight into market life and commerce in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) capital Bianjing, or modern-day Kaifeng, Henan Province.

Urban management played an instrumental role in the administration and growth of cities in ancient China. Effective urban management not only reflects strong government functions, but is also a means to advance social and economic development. A review of how urban management evolved in ancient China can shed light on present-day city building and management.

Closed, mandatory management

In the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 BC), there were city markets classified as fairs, bazaars, morning markets and afternoon sessions, and regular and irregular markets. At that time, officials were appointed to administer markets along with corresponding management systems. They were responsible for monitoring peddlers and commodities coming in and out of the city gate, regulating the distribution of stalls and shops, determining prices and barring trade of prohibited goods.

As cities expanded during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period (770-221 BC), they were more and more closely related to markets. In cities there were settlements, large temples, defensive facilities, handicraft workshops and more. The management system was modeled after that of the Western Zhou Dynasty.

After the Qin Empire (221-206 BC) unified China and implemented an administration system of prefectures and counties, known in Chinese as junxianzhi, most cities became seats of governments. Expansion of Qin territory brought about a growing number of cities. After the establishment of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 45), increasingly stable social order laid a good foundation for urban development.

In the Han Era (206 BC-AD 220), li (village) was the lowest unit in the administrative hierarchy, where residents were governed by village officials including the village chief and elders. The village chief was the highest-ranking official in the village, charged with tasks of collecting taxes, assigning statute labor and punishing criminals. Elders were mainly in charge of promoting agricultural development and civilizing the villagers.

The Han regime attached particular importance to supervising commercial activities in cities, and therefore formulated a rigorous market management system. The institution of markets was subject to government control, and they were divorced from residential areas.

The markets were managed in a closed-end manner, each equipped with officials, such as market head and market director, who were duty-bound to maintain public security, specify measurements and enact prohibitions.

Vendors were required to register before trading at the market. In addition, the Han imperial court valued regulation of market prices so much that it designated standards bureau directors to regulate prices.

During the Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties (220-589), political disunity and cultural turbulence substantially enhanced the military function of cities and urban management featured military-political integration.

Major changes took place in the central government during this period, as the three departments quickly rose to prominence, consisting of the Department of State Affairs, the Secretariat and the Chancellery.

The Department of State Affairs was most concerned with urban management. Since the reign of Cao Wei (220-265), one of the three major states that competed for supremacy over China in the Three Kingdoms period (220-280), the Department had become the top-echelon administrative apparatus in the country and naturally the paramount authority for nationwide urban management.

Headed by a director, the Department of State Affairs was divided into a number of minister-led sections that covered all aspects of urban management. For example, the Minister of Justice was responsible for public security and Minister of Waterways directed water supply and discharge.

Fall of precinct-market system

Urban management during the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties placed the closed precinct-market system at the core, confining urban residents and commercial activities to specific areas and exercising dual restrictions, temporal and spatial.

Like the Sui court, the Tang court maintained its capital at Chang’an, or modern-day Xi’an, Shaanxi Province. In the suburbs of the capital, there were important areas in addition to precincts and markets, namely, streets. Urban territorial administration in the Tang Dynasty was therefore based upon precincts, markets and streets.

In late Tang Dynasty, the boundary between precinct and market was gradually broken, leading commerce to extend to areas outside markets. Big cities, such as Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province and Bianzhou, modern-day Kaifeng, Henan Province, saw night markets emerging. Strict prohibitions requiring precincts and markets to be separated and markets closed at sunset were lifted.

During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960), cities underwent dramatic ups and downs. The precinct-market system was inadaptable to social development. In April 955, when Emperor Shizong (954-958) of Later Zhou (951-960) was in power, a decree was passed to construct roads, storehouses and barracks. Civilians were also allowed to build houses along the road at their will. As such, a new street system was gradually brought into being.

In the early Song Dynasty (960-1279), the precinct-market system from the Tang Dynasty was carried forward. While a sharp distinction was drawn between residential and commercial areas, restrictions were imposed on residents’ life and commercial activities. Nonetheless, due to the impact of commodity economy, the system was also flexible.

In 965, during the rule of Emperor Taizu (960-976), night markets were permitted after three drumbeats from the drum tower of the Kaifeng Court. This signaled to commoners they were allowed to go out before midnight. During the reign of Emperor Renzong (1023-1063), vendors were allowed to set up shops on the street as long as they paid taxes. During the reign of Emperor Shenzong (1068-1085), the drum tower of the Kaifeng Court no longer sounded drums and guards in the capital no longer patrolled at night.

Following the lifting of government bans, walls marking the boundary of precinct were dismantled, bringing an end to the closed precinct-market system and signaling the beginning of a new open pattern of cities.

Continuous reforms

After the breakdown of the precinct-market system, the township-precinct system superseded it for new territorial administration, marking a major reform in city management in ancient China. The replacement of closed and mandatory management in favor of street-based governance undoubtedly represented progress.

In the Liao (907-1125), Jin (1115-1234) and Yuan (1206-1368) dynasties, ethnic minorities were incorporated into urban management.

In the Yuan Dynasty, in particular, urban administration was evidently different despite the inheritance of the township-precinct system. Except for remote areas including modern-day Sichuan, Hubei, Hunan and Yunnan provinces, each route featured an administration office.

Cities grew on an unprecedented scale during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), when a host of large-sized, densely populated, industrially and commercially prosperous cities sprung up. Shops were opened facing the street, from centralized to scattered into a more reasonable distribution pattern that facilitated residents’ life.

In the early Ming Dynasty, the street-alley system was adopted in Yingtian Prefecture, modern-day Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. A household registration was introduced to manage residents, whose dwellings were defined by their occupations.

After the central government moved to modern-day Beijing, an exclusive organ was instituted to administer the capital, namely, the Warden’s Offices of the Five Wards. Borrowed from the Yuan Dynasty, the offices took charge of police patrol, fire watchers, and maintained general peace and order in the capital.

City management in the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) was characterized by the separate governance of the Manchu and Han people. Take the capital Beijing, for example. The Qing imperial court divided the capital into the outer and inner cities. The inner city accommodated the Manchu people, while the Han who originally resided in the city were relocated in the outer city, leading to different community division and management.

The management system resulted in entirely different structures of residents, as the inner city was largely populated by the Manchu people, while the gentry, businessmen, craftsmen and handicraftsmen lived in the outer city.

Zhang Chunlan and Meng Yue are from the Center for Studies of Song History at Hebei University.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE