Farewell to Utopia: Current state of Chinese art

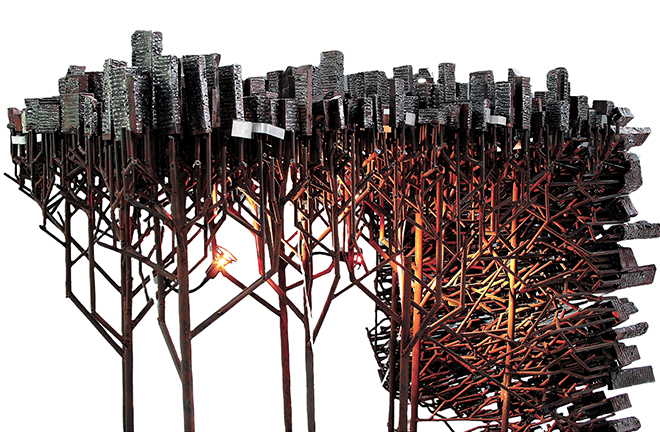

“City,” a welded metal sculpture by Lin Yao Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

As a member of the “post-1980s” generation, I have spent more than two decades immersed in the world of art. Since entering university in 2000, I have witnessed the golden age of Chinese contemporary art. The first decade of my career was dominated by terms closely linked to politics, economics, and culture—artworks, myths of overnight wealth, money, power, exhibitions, capital, market, conceptual art, biennales. The following ten years introduced a different vocabulary, rooted in interdisciplinary exploration: curators, exhibitions, communities, new media art, participatory art, rural revitalization through art, and AI art.

If the 1.0 version of contemporary art centered on competition within professional circles, the 2.0 version seems to have shifted decisively toward broader public engagement and accessibility.

Boom period of contemporary art

Setting aside questions of aesthetic production, we might refer to the first period as the boom phase. It was a time when artistic creation converged with market forces, and artworks became a means of expressing—or consuming—social wealth. The soaring prices reported by major auction houses around the world bear testimony to this phenomenon.

There’s a saying that whenever a society reaches a stage of relative affluence, it begins to develop mechanisms for wasting wealth—art and war, in this sense, are often seen as siblings. As a distinct form of commodity, contemporary art epitomizes the paradox of being functionally useless yet financially valuable. Bathed in the dividends of its era, contemporary art once emerged as a dazzling jewel, capturing widespread attention and enthusiasm. In terms of sheer output, it entered a period of unprecedented prosperity: the number of artists and artworks grew exponentially. Especially between 2004 and 2014, galleries, collectors, dealers, art institutions, and art districts sprang up at home and abroad like mushrooms after rain. Amid this flourishing ecosystem, the utopian dream of contemporary art naturally took root.

Of course, we cannot overlook the “coincidental” union between art academies and the market—a partnership that significantly amplified the influence and appeal of contemporary art. If we pause to consider: where did this wave of artists originally come from? The answer is obvious—art schools. Universities and art academies serve as the essential foundation for both talent cultivation and academic support. They not only provide aspiring artists with solid training in foundational knowledge and artistic skills, but also foster reflection and inspire creative expression through theoretical research in art history, aesthetics, and cultural criticism. It’s no exaggeration to say that the explosive growth of contemporary art would not have been possible without these institutions as vital incubators.

The first generation of artists who embodied the myth of art-generated wealth largely emerged from universities and colleges. The identity of “teacher/artist/successful artist” seemed both natural and legitimate, just as the connection between artwork, exhibitions, and financial gain appeared entirely justified. Within this art world, which unfolded over more than a decade, embracing the market, following the unspoken rules of art-world networking, and intensely pursuing success became common survival strategies for many young artists—strategies that proved effective during the boom years.

Artists, artworks, museums, galleries, dealers, and collectors seemed to form a closed loop of production and consumption—intentionally or otherwise—resulting in a seemingly “utopian” production chain. Gradually, the idea that “art equals wealth” became an alluring dream within easy reach, one that lingered in the minds of artists and refused to fade. Meanwhile, the essence of art itself was increasingly pushed to the margins.

A disrupted ‘pre-’ contemporary artistic experience

In the past decade, the steady emergence of new art-related terms in the media suggests that contemporary art is entering a new phase. The “pre-” contemporary art experience may be losing its relevance, and today’s art faces a host of new and pressing challenges. These include the loss of poetic sensibility in visual art, the digitization of traditional art, the playful nature of new media art, the public engagement of community art, the experimentalism of conceptual art, the digital and technological aspects of AI art, and the retreat of political pop. In their place, consumerist imagery is on the rise, and an aesthetic wave of “smoothness” is increasingly enveloping our lives and thoughts.

These are clearly issues that visual art alone cannot resolve; after all, the digital-intelligent era offers art many new directions and choices. There is a certain melancholy to all this. Those of us who witnessed the myth of art-generated wealth also saw a generation full of idealism, avant-garde experimentation, and critical spirit—a truly romantic and passionate youth.

The precarious state of visual art today signifies that it is undergoing a new wave of upheaval. This ancient law, inscribed across millennia of human art history, is now playing out anew, whether as deconstruction or rebirth.

Just as we marvel at the dazzling diversity of today’s art, the money games continue. The myths fueled by capital still provoke astonishment with the sound of the auctioneer’s hammer. The young dreamers of that era have quietly entered middle age, and what was once fervent artistic “deification” now feels like a fleeting illusion. Aside from the select few who have entered the hall of artistic fame, some have turned toward purer artistic creation, some to art education, and others have exited the scene altogether.

Alternative art space spreading like wildfire

Beyond the mainstream of contemporary art, art museums and galleries in first- and second-tier cities have taken on increasingly important roles in art education, gradually forming an evaluative system of artistic discourse centered around the public. Visiting such institutions has become an essential form of aesthetic nourishment in everyday life.

Beyond this, sparks kindled outside the mainstream are also spreading like wildfire. In an article discussing the “wildgrass-like alternative spaces in regional cities,” these spontaneously formed, small-scale venues—genetically distinct from mainstream galleries and museums—are called “alternative spaces,” described as “a reserved patch of land, a warm web, a circuit formed by friends holding hands.” Their significance lies chiefly in their roles as “shelters, connectors, nurturers, autonomous zones, and sites of resistance.” They preserve independence of thought while engaging in dialogue between local contexts and globalization.

The article places particular emphasis on highly localized art spaces and projects in cities such as Guangzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan, and Xi’an. These organically evolving spaces reflect what Gilles Deleuze once theorized as the rhizome—non-hierarchical, decentralized, and constantly growing through unpredictable linkages—roaming freely across myriad plateaus of art.

A new artistic scene is emerging. Unlike earlier phases, today’s healthy art ecosystem resembles a mature and systemic design: government support and intervention, coordination among communities and local organizations, mutual promotion between universities and the market, and a relatively objective system of artistic evaluation all contribute to this emerging framework.

When I see the words “contemporary art” now, to me, they represent the “contemporary” of yesterday. Contemporary is, after all, a time-bound term—but in my case, it evokes the past two decades of fervor, now gone. That once utopian era—filled with idealism, artistic myth-making, and a spirit of critique—has already left a bold and indelible mark on the history of art.

As the art market cools, contemporary art is increasingly approached with critical distance and sober reflection. After all, every art history is a contemporary history. So where is today’s art headed? The times have changed. Contemporary art has fulfilled its mission for a particular stage. Now, it is branching off, sliding—or perhaps falling—onto new tracks. In time, it will arrive at a renewed state of coherence and self-sufficiency.

Zhong Shu is an associate professor from the Chengdu Academy of Fine Arts at Sichuan Conservatory of Music.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE