Improving brain chip regulation through intelligent governance

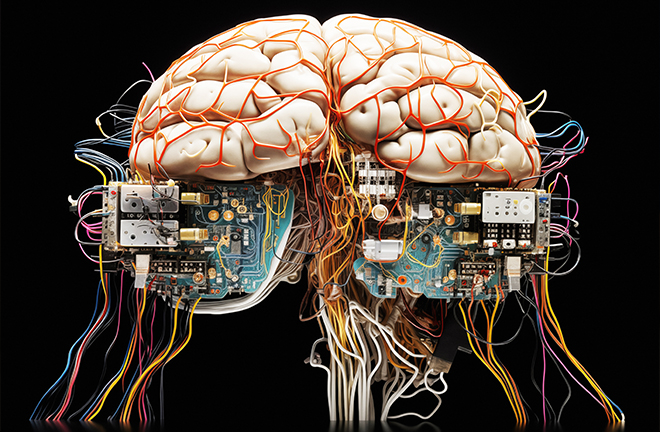

Brain chip technology may eventually enable seamless integration between the human brain and computer systems. Photo: TUCHONG

Brain chips represent one of the most significant breakthroughs in neuroscience in recent years. Beyond their capacity to treat brain injuries, these chips may one day restore memory, emotion, and foundational knowledge, and augment human sensory perception and cognitive ability. As this technology evolves, it may gradually blur the line between biologically enhanced humans and artificial intelligence, presenting unprecedented challenges to existing regulatory frameworks. Balancing safety and innovation requires a nuanced understanding of the risks posed by brain chips and a willingness to rethink traditional modes of oversight.

Regulatory lag in face of emerging technologies

In principle, any effort to understand, assess, predict, control, or enhance human behavior constitutes a potential application of neuroscience. Such applications must confront the difficult task of distinguishing enhancement from therapy and comprehensively consider the associated risks. For instance, brain chips are susceptible to hacking, potentially endangering the life and health of the implant recipient. Erasing or altering a person’s memory or thought processes would be tantamount to performing a lobotomy—harmful in ways that existing criminal law is ill-equipped to address. Moreover, neural data stored in these devices may be vulnerable to misuse or exploitation. While developers and manufacturers should bear some responsibility, no specific laws and regulations are currently in place.

Information asymmetry: Effective regulation requires that regulators have access to sufficient and accurate data. However, due to the interdisciplinary nature of brain chip development, regulators often struggle to stay abreast of technological advances and lack the tools for integrating data and making informed decisions. Furthermore, it is challenging to identify the right timing for regulatory interventions: premature regulation could stifle innovation, while delayed regulation may fail to mitigate risks before negative consequences arise.

Inflexible ethical review mechanisms: As China’s “Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans” mandate respect for and protection of participants’ right to informed consent and autonomous decision-making, double-blind experiments are deemed noncompliant with the provisions, making it difficult to establish control groups. However, brain chip development requires the accumulation of vast amounts of individualized data to ensure technical stability and expand applicability.

Legislation lagging behind technological advancement: First, regulatory lag is objectively inevitable, as the law cannot accurately predict the future consequences of emerging technologies and must rely on limited present-day information. Second, the development of brain chips involves externalities and should serve the public interest, yet terms such as “encourage” and “promote” in existing Chinese technology law are not linked to civic rights nor translate into administrative obligations. Third, neurotechnology involves multiple stakeholders—the government, developers, and the general public—whose overlapping interests cannot be effectively coordinated by a single legal framework.

Preparing for human-computer symbiosis

A defining feature of brain chip technology is its potential to bring about “organic human-computer integration.” Yet existing regulatory frameworks have largely failed to keep pace with the technological trajectory and to account for the prospect of human-computer symbiosis. Therefore, ethical and legal oversight should be complemented by intelligent governance. Brain chip regulation should focus on data-driven approaches, the diversification of regulatory tools, and the adherence to core principles such as transparency, equity, and intelligence, thereby building a real-time, dynamic regulatory system.

Data and information lie at the core of brain chip regulation. Intelligent governance leverages data through collection, analysis, feedback, and sharing. Regulators need accurate and comprehensive data to understand stakeholder behavior and systemic risks, which enables dynamic assessment of appropriate timing for clinical application and commercialization. In turn, developers and other stakeholders can observe the responsiveness and timeliness of regulatory interventions through data, feeding that information back into product design and development.

Intelligent governance emphasizes tapping into the potential of all stakeholders and fully harnessing intelligent technologies. In China, several areas can be prioritized at this stage: developing refined systems for brain chip data collection and decoding, establishing phased early warning mechanisms for technological risks; and creating agile regulatory feedback loops.

In conclusion, the regulation of brain chips must adapt to the interactive co-evolution characterizing human-computer symbiosis, embrace intelligent governance as its guiding principle, adopt digital-driven approaches to enable stakeholder autonomy and self-discipline, while also ensuring coordination and integration with traditional ethical review and legal oversight.

Zhang Man is an associate professor from the Law School at Northwest University.

Edited by WANG YOURAN

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE