Institutional advantages of Qin State key to unifying China

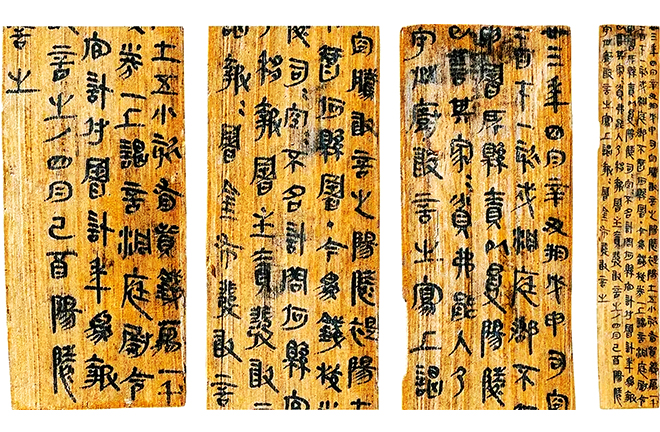

FILE PHOTO: Bamboo slips revealing details of life during the era of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, unearthed from Liye, Hunan Province

The Qin state (770–207 BCE), having long coexisted with the Rong-di (“barbarian”) peoples, was regarded by Zhongyuan (Central Plains) states as a non-Han tribe that was culturally inferior. Following the Shang Yang reforms, Qin embraced Legalism while disregarding traditional rites and music, further fueling disdain from Zhongyuan states. The perception of Qin as “barbaric” and “backward” has endured, with some still viewing its unification of China as a triumph of barbarism over civilization. While Qin undoubtedly retained certain primitive customs and institutions, reducing its success to a victory of barbarism and backwardness over civilization and advancement risks oversimplifying history and is logically flawed. Excavated bamboo and wooden slips reveal that Qin’s institutions—particularly in social hierarchy, land ownership, and taxation—were key factors in its superiority over its six major contenders and its eventual unification of China.

Social hierarchy

The six states branded Qin a “nation of tigers and wolves,” noting that “Qin soldiers fearlessly charged into battle, often discarding their armor, carrying a severed head in one hand and a captive in the other.” This fierce combat spirit was driven by the strong incentives embedded in Qin’s social hierarchy. Established through the Shang Yang reforms, this system encompassed all social strata, from nobility to convicts, and was distinguished by its openness—particularly in its rank-based structure. Unlike the Zhou (1046–256 BCE) aristocracy, where noble titles were hereditary and inaccessible to commoners, Qin granted ranks based on military merit: “Those who have military achievements shall receive higher titles according to their rank,” “members of the royal family, unless they have military achievements, shall not be included in the official register,” and “those without merit, even if wealthy, shall have no distinction.” Even slaves could ascend the ranks through battlefield accomplishments. The Qin-era bamboo slips housed by the Yuelu Academy at Hunan University record a case of an enslaved individual who was promoted to gongshi, the first noble rank, after earning military merit. This meritocratic system, in contrast to the rigid Zhou hierarchy, served as a powerful motivator for commoners.

Another defining feature of Qin’s social stratification was its pragmatism. Scholars have identified multiple political, economic, and legal privileges associated with its rank system, including status recognition, eligibility for official appointments (later abolished), land ownership, judicial leniency, and the ability to ransom family members. As stated in historical records, “Rank determines land allocation, attire, and household hierarchy.” The strongest motivation for Qin soldiers in battle was the direct link between military merit and noble rank, with each title granting tangible benefits.

Comprehensiveness was another key characteristic of Qin’s social hierarchy, evident in three aspects. First, a fully developed rank structure encompassed all social groups, from commoners and soldiers to convicts and slaves, with titles extended from 18 to 20 ranks. Second, a strict reward-and-punishment mechanism ensured that military achievements earned rank, while crimes led to rank demotion or loss. The Yuelu Qin slips confirm such cases, including second rank-holders revoked of their titles due to desertion. Third, multiple pathways for social mobility allowed individuals to change status through merit, punishment, or skill. The Yuelu Qin slips record enslaved individuals who, through craftsmanship or labor, transitioned from lifelong servitude to commoner status.

With its openness, pragmatism, and comprehensiveness, Qin’s hierarchical system far surpassed the rigid aristocratic structures of the Zhou Dynasty and the six states. By incentivizing and enabling social mobility, it played a crucial role in Qin’s ultimate dominance over its rivals.

Land ownership system

The saying “To the people, food is heaven” underscores the fundamental importance of land as a means of subsistence. Qin implemented a land distribution system far superior to that of the other six states, distributing land according to the household head’s status. According to the Book of Lord Shang, “A soldier can be awarded a noble title of one rank, an additional one qing of land, and an additional nine mu of residential land, for killing one enemy on the battlefield.” The Second-Year Statutes from the early Western Han (202 BCE–25 CE) further details land ownership by status, ranging from 1.5 to 95 qing for high-ranking nobles to 1 qing for commoners and even 0.5 qing for certain convicts. While exact allocations may have differed from Qin’s policies, the hierarchical land distribution principle clearly originated from Qin.

Qin also adopted the largest mu system of its time. The Field Statutes recorded on the wooden slips unearthed in Qingchuan, Sichuan Province, describes a unit of land called a zhen, measuring 240 steps, significantly exceeding the Zhou Dynasty’s 100-step mu. The measurement of mu was the largest in the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE), surpassing those of Han, Wei, and other states. During the Six Clans Period of the Jin state, the Fan and Zhonghang clans used a 160-step mu, the Han and Wei clans adopted a 200-step mu, and the Zhao clan implemented a 240-step mu. After the partition of Jin by Han, Wei, and Zhao, the land measurement systems of the three states likely remained largely unchanged. Qin’s 240-step mu system was equivalent to that of Zhao, but 1.5 times that of Han and 1.2 times that of Wei. Sun Wu had already predicted the political trajectory based on these differences, foreseeing the fall of the Fan and Zhonghang clans first, followed by the Zhi clan, then Han and Wei. If Zhao preserved its system, he suggested, Jin would ultimately return to it. This reasoning implies that a larger mu system conferred institutional advantages. After unifying China, Qin standardized this system nationwide, where it remained in use through the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) and Three Kingdoms Period (220–280).

Qin’s land allocation system provided all commoners with land, while its large mu system maximized actual land holdings per person. This approach encouraged migration, boosted agricultural productivity, and laid the economic foundation for Qin’s military and political dominance.

Taxation advantages

Qin’s primary taxes consisted of land tax and household tax, with no evidence of a head tax. Excavated records on bamboo and wooden slips suggest taxes in Qin were also relatively low. As confirmed by General History of Chinese Economy: Qin and Han, land tax followed the “one-tenth” system in the Warring States Period as well as the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE). Qin slips from Liye in Longshan County, Hunan Province, indicate that tax fields accounted for 8.52% of total cultivated land, aligning with this rate. According to The Art of War recorded on the Han slips from Yinqueshan in Linyi, Shandong Province, the Fan, Zhonghang, Han, and Wei clans once levied a “one-fifth” tax, which Wei later reduced to one-tenth under Li Kui’s reforms. Though higher than the Han Dynasty’s “one-fifteenth” or “one-thirtieth” rates, Qin’s tax burden was the lightest among its contemporaries.

Qin’s household tax was also moderate. The Yuelu Qin slips state that households paid in grain or money in the fifth and tenth months annually—32 qian, roughly equivalent to 4 to 5.3 days’ wages for laborers, or 1.28 dan of glutinous millet or 1.6 dan of husked glutinous millet based on contemporary prices. This tax level persisted into the early Han era with only minor reductions, which provides evidence that the Qin’s household tax system was a well-designed and sustainable institution worth maintaining.

Though Qin’s social hierarchy, land policy, and taxation system were not designed primarily for popular welfare, they were superior to those of the six states and aligned with the people’s aspirations for upward social mobility, land ownership, and stability in an era of upheaval, laying the institutional foundation for Qin’s unification of China. This disproves the notion that its victory was merely “barbarism triumphing over civilization;” rather, Qin’s success stemmed from responsive institutional design that met public aspirations.

However, these policies comprised only part of Qin’s institutional framework. Its reliance on harsh penal laws and heavy labor conscription placed significant burdens on the population. Before unification, Qin’s strict governance was offset by wartime opportunities for commoners to earn noble ranks, acquire land, and secure livelihoods, which masked the severity of its legal and labor policies. After unification, large-scale warfare ceased, and opportunities for commoners to obtain titles sharply decreased. Moreover, the continuous process of atoning for crimes and absolving family members gradually depleted these titles. The administrative shortcomings of the Qin regime, previously obscured by the system of titles and other social distinctions, began to emerge. Although the land ownership institution and tax rates remained unchanged, social mobility stagnated, land acquisition became difficult, and living conditions worsened. The accumulation of harsh legal oppression and taxation ultimately overwhelmed the populace, leading to Qin’s collapse within two generations.

As Guanzi observes, “A state thrives when governance aligns with the people’s will and collapses when it opposes it.” Qin’s institutional changes and its rise and fall vividly illustrate this principle.

Su Junlin is a professor from the School of History and Culture at Southwest University and a visiting research fellow from the Bamboo and Silk Manuscript Research Center at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE