Is the US really headed for decline?

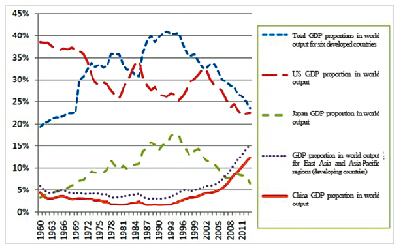

The graph shows economies’ GDP proportions in world output from 1960 to 2013.

Japanese-American political scientist Francis Fukuyama has attracted mixed views for his observations about the shifting global economic order over the past two decades. His essay “America in Decay - the Sources of Political Dysfunction” (September/October 2014 issue) published in U.S. bimonthly magazine Foreign Affairs generated heated discussion.

U.S. economy shrinking

The U.S. GDP proportion in world output is indeed declining. Great changes have taken place in the world pattern in the decades since World War II, with three groups of economies including Europe, Japan and emerging market economies successively rising.

The U.S. economy accounted for 38.5 percent of the world’s total economy in 1960, dropping to 25.2 percent in 1995. It hit 32.2 percent in 2002, which marked a turning point. The U.S.-world economy ratio has eased about 1 percent annually since then. It slumped to 22.4 percent in 2013, triggering calls about the “decline” of the U.S..

According to the graph, the total of GDP proportions of six developed countries – Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Canada and Japan – exceeded 40 percent of global output in 1995. Japan’s economy hit its postwar peak at 17.7 percent of the world economy the same year. However, from 1994 onwards the total of the six countries’ economies declined around 1 percent annually, falling by 20 percent in total. Their total dropped to 23.6 percent by 2013.

Japan’s GDP proportion dropped about 1 percent every two years to 6.5 percent in 2013, falling by 10 percent in total. It rose from 3.2 percent in 1960 to 17.7 percent in 1994 and then gradually declined, plummeting to 6.5 percent in 2013 and causing unease in Japan.

By contrast, China and other emerging market economies have developed rapidly during this period. For example, the proportion of all developing countries in East Asia and the Pacific region began to rise 10 years ago, from about 5 percent to 15.2 percent in 2013. In particular, China’s economy is growing at a rapid pace, escalating from 3 percent 10 years ago to 12.3 percent in 2013. More remarkably, China’s GDP accounted for 9 percent of the world total in 2010, exceeding Japan’s 8.5 percent for the first time.

Wary of hype about U.S. ‘decline’

The graph indicates that fears of the U.S. “decline” appeared about a decade ago when GDP proportions of the six big developed countries were gradually declining, while those of emerging economies, especially China, were rapidly growing.

Fukuyama noted in his essay that the GDP proportions of the U.S., Japan and European economies are falling due to the rise of emerging economies, especially China, leading some to speculate this rise and fall represents a zero-sum game.

The so-called decline is not only a problem for the U.S.; it is a logical process in world economic development. Every economy has its own cycle, from infancy to maturity to eventual decline. It is unnecessary to fuss about the similarity between society and nature.

U.S. long-term status can’t be ignored

GDP, as a form of hard power, cannot be chosen as a sole indicator of “decline” when assessing U.S. strength; soft power should also be taken into careful consideration. On the whole, aspects that reflect U.S. soft power, such as economic vitality, innovation and competitiveness, remain competitive advantages. The U.S. generally ranks within the top 7 in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, which is viewed as an important indicator of each country’s soft power.

The U.S. always polls well because rankings are determined by 12 aspects: system, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market development, technical preparation, business capabilities and innovation.

For the purpose of catching up with the U.S., Europe devised the Lisbon Agenda, an action and development plan for the economy of the EU between 2000 and 2010. Another plan, Europe 2020, was adopted in 2010 to spell out the EU’s second 10-year growth strategy. The EU exceeded the U.S. in GDP as early as 10 years ago due partly to its eastward enlargement of the Eurozone. However, a large economic gap still exists between the U.S. and EU.

Some facts and figures listed in Fukuyama’s article are of no practical significance. For example, he held that U.S. bureaucracy is no longer full of vitality and efficiency, as 45 percent of its new employees are veterans instead of those from elite schools. Despite this, many politicians and presidents are from elite schools. Furthermore, issues addressed in Fukuyama’s article, such as prevailing reciprocal altruism, corrupted interest groups and soaring lobby enterprises, also indicate the transparency of U.S. public policy as well as the high operating cost of its system.

Some Americans trust the market over the government. Tens of thousands of people demonstrated in Washington DC in September2009 to protest the universal health security plan proposed by U.S. President Barack Obama, which they believed was unconstitutional and against popular will.

The U.S. social security system, which involves four social groups, also features market traits.

Events like Occupy Wall Street, a protest movement that began in September 2011 in Zuccotti Park located in New York City’s Wall Street financial district, received global attention and spawned the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide. However, these events cannot reverse the course of history. The U.S. remains incomparably competitive amid its “decline” based on its social security system.

By contrast, Europe is short of vitality and competitiveness partially because of its social security system that supports so many on welfare.

To some extent, the U.S. social security system reflects its soft power. The U.S. status cannot be neglected for quite a long time. We should objectively treat ideas in Fukuyama’s article, but Fukuyama should also analyze the rise and fall of economies from more perspectives.

Chinese link: http://sscp.cssn.cn/xkpd/gjyk/201410/t20141015_1363338.html

Revised by Tom Fearon

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE