Classics present distinct developments in China and West

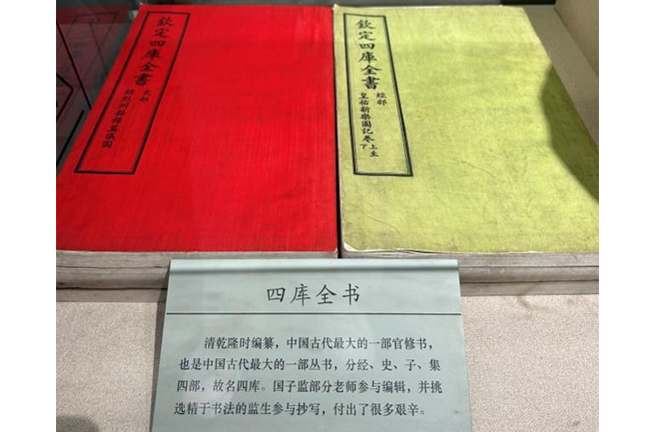

Siku Quanshu [Complete Library in the Four Branches of Literature] on display at the Imperial Academy in Beijing Photo: Yang Lanlan/CSST

Classics, as a discipline dedicated to studying the classic works of ancient civilizations, holds significant cultural and academic value worldwide. The history of Western classics and the modern rise of classical studies in China both reflect the important role that classics play in national development and cultural inheritance. To discuss the connotations of classics and its relations with national development and the modern world, CSST interviewed Liu Xiaofeng, a professor from the Center for Classical Civilization at Renmin University of China.

Different connotations

The definition of classics and the controversy surrounding it within academia are complex topics that involve various cultures, historical contexts, and academic traditions. Liu sees classics as an interdisciplinary field centered on the study of classical works, noting that defining it within the scope of modern academic disciplines presents many challenges, as it draws on classical philology, philology, historiography, and even philosophy. The world today is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century. Over the past two decades, classics in Western academia has gradually been overshadowed by modern radical ideologies, leading to a noticeable decline in its influence. In China, by contrast, classical studies have emerged with new vitality.

To fully understand this phenomenon, we must first clarify that the definition of classics by Chinese scholars inevitably differs from traditional definitions in Western academia, Liu continued. In the Western academic context, classics specifically refers to the study of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, covering many fields such as literature, philosophy, history, and art. While it also includes the compilation and interpretation of unearthed documents, the core focus remains the study of classic works that have had a profound impact on later generations.

In 2nd century Rome, the term “classic” came to be used to describe works that were worthy of emulation due to their stylistic and spiritual qualities. These works were generally regarded as cultural standards for nurturing political leaders, including a vast array of writings from ancient Greek and Roman poets, philosophers, orators, and playwrights, which were considered classic due to the exceptional moral character and rhetorical skill they embodied. Nevertheless, Western classical studies do not strictly distinguish between ancient texts and classics, though obviously not all ancient works are classics. Therefore, Western classical studies are almost synonymous with our classical philology.

In China, classical studies are not limited to the expansive fields of classical philology or ancient text compilation. They also include Confucian studies centered on the Thirteen Classics, research on the “Masters” (pre-Qin philosophies), and studies in classical poetry and prose. Chinese classical studies span various fields, such as paleography, the compilation of ancient books, classical philology, ancient literature, history of historiography, history of ancient philosophy, and even archaeology (such as the study of Chu bamboo slips). Unlike in the West, where classical studies are largely consolidated within a single academic discipline, classical studies in China are more dispersed.

Western classics emerged alongside shifts in geopolitical landscapes, while Chinese classical studies arose with the fall of the imperial system in the early 20th century, Liu added. Over the past century, China’s modern cultural and educational systems have remained in flux amid historical tribulations. As we all know, to this day, our disciplines are still undergoing continuous adjustment. Our classics, therefore, does not yet have an independent place within universities and research frameworks. But we mustn’t conclude that it is marginalized; rather, it has yet to form its own system, which leads to considerable discussion and even debate within academic circles. Liu stressed that at present, the essence of classical studies lies in activating the profound philosophical and cultural insights of ancient classics for contemporary relevance. It is not solely about the study of ancient texts but also about the philosophy of the mind. Therefore, it should not be equated with classical philology, paleography, ancient historiography, or even archaeology, although these disciplines are essential to classical studies. The primary focus of classical studies must be the classic texts themselves, with other fields serving as supportive disciplines.

Interwoven with national development

From the rise and fall of the ancient Roman Empire to the profound transformations of today’s world, a strong link exists between classical studies and national development. When discussing the relationship between the compilation of ancient texts and the vicissitudes of great powers, we can observe a historical pattern from the early Han Dynasty, through the Sui, Tang, Song, and Qing dynasties showing that “collecting and compiling classics in flourishing ages” is a well-established historical fact, Liu said. The first large-scale compilation and transmission of ancient Greek texts occurred after the formation of Alexander’s empire. Despite the empire’s later fragmentation into three parts, the Hellenistic political ideal persisted. Greek scholars of the era, driven by the ideal of pursuing a unified empire, sought to organize and transmit the classics of ancient Greek civilization. After the Roman Empire unified the Mediterranean region, it adopted Hellenistic ideals and integrated them with its own cultural traditions. Following the overthrow of the Western Roman Empire by barbarian tribes, the Eastern Roman Empire consciously inherited the traditions of ancient Greek civilization and engaged in notable efforts to organize ancient texts.

Since the 14th century, Italian humanists’ search for ancient Greek and Roman texts became a hallmark of the Italian Renaissance. We should recognize that the so-called Italian Renaissance was in fact a political revival for Italy, even though it ultimately did not succeed in forming a unified, modern nation-state. Petrarch, celebrated as the father of the Italian Renaissance, is renowned for his efforts in collecting and compiling ancient texts. However, we must not forget that he was also an active politician, advocating for a unified Italy. Among those who played an important role in the collection and study of classical literature were not only the rulers of Florence, but also the Popes of the Roman Curia, underscoring how the search and compilation of ancient Greek and Roman texts was, in many respects, akin to a “state act.”

After the 16th century, with the expansion of global exploration, the Atlantic Ocean gradually replaced the Mediterranean as the center of trading, leading to a decline in Italy’s international status while the positions of Britain, France, and especially the Netherlands began to rise. This shift gave rise to the “Northern Renaissance,” shifting the organization of ancient texts to political entities north of the Alps. By the 19th century, the highly feudalized regions of Germany experienced a strong impulse toward political unification, and classical studies became one of the first institutionalized disciplines in Germany. Prussian minister of education Wilhelm von Humboldt not only attached great importance to classical education in universities but also established a secondary education system that prioritized classical philology. This had a considerable impact on the subsequent growth of German classical studies. The flourishing of Western classical studies is closely tied to the rise of modern European monarchies. In contemporary civilizational dialogues and international relations, we must not overlook these historical factors, Liu concluded.

Edited by YANG LANLAN

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE