Human-Machine Communication improves elderly care

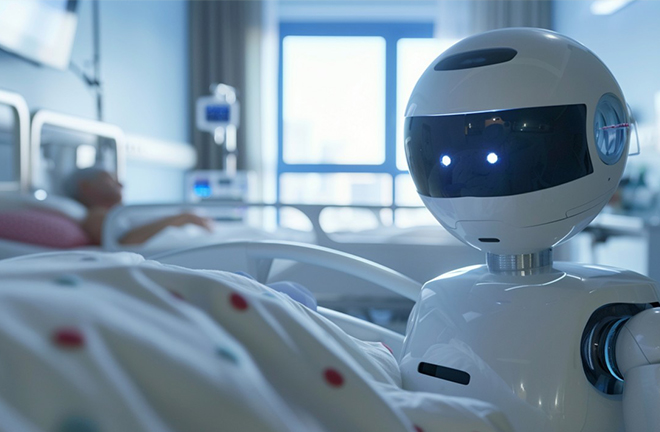

Robots, by simulating human behaviors and responses, can mimic interpersonal communication and emotional interactions as they engage with humans. Photo: TUCHONG

According to the resolution adopted at the Third Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee, it is crucial to “actively respond to population aging,” and “refine the policies and mechanisms for developing elderly care programs and industries.” In particular, this reform emphasizes the role of intelligent technologies in supporting elderly care services and industries.

As China’s population ages and birth rates decline, traditional geriatric care services are challenged by resource shortages and inefficiency. However, intelligent technologies like robotics promise to innovate care models. Smart elderly care could become a crucial tool in managing an aging society. Central to this is the interactive exchange of information between humans and intelligent technologies—referred to as Human-Machine Communication (HMC).

HMC is “the collaborative process in which humans and machines use information to create and engage in social reality.” HMC research posits that machines, as communicative agents, possess the ability to autonomously interact and act, potentially influencing human emotional experiences, lifestyles, and even social relations. Therefore, studying the ethics, laws, and social acceptance of robot-assisted elderly care from an HMC perspective can help improve the quality of life and enhance governance in an aging society.

Geriatric care robotics

Robots already exist which perform standard functions that meet the diverse needs of aging people. For instance, service robots can assist the elderly with daily tasks including object delivery and retrieval, household chores, dispensing medications, and generally working as assistants. Companion robots provide emotional support and psychological comfort, helping to alleviate loneliness. Medical care robots offer services to geriatric patients who require long-term nursing, easing the burden of caregiver shortages.

Elderly individuals have complex needs, depending on their stage in life, health, living situation, and personal experiences. Expectations for robot functions often overlap and intertwine.

As subjects in human-machine communication, how can robots understand human needs, and construct meaning in specific contexts, while maintaining their own subjectivity, intentionality, and morality? This question is not only a technical issue but also an ethical and legal one.

Researchers are also investigating whether the use of robots inevitably leads to the absence of human companionship. Traditional Chinese values of filial piety emphasize time spent with parents as the primary way to show respect, particularly by surrounding the elderly with children and grandchildren. As people age, they increasingly value close family connections and companionship. When robots become part of elderly people’s lives, do they facilitate social integration, or obstruct social connections? Will robotics create a new form of social illusion? These are critical issues in the governance of an aging society that need careful attention, along with questions about how to integrate humanistic thinking into the application of intelligent technology from the perspectives of meaning sharing, relationship restructuring, and cultural construction in human-machine communication.

Technological rationality vs. human sensitivity

Robots’ decision-making logic is based on algorithms and data analysis, and it is precise and efficient. Meanwhile, human emotions are complex, weaving together psychological, social, and cultural dimensions. HMC research suggests that humans tend to unconsciously perceive machines as human and form quasi-social relationships with them. Robots, by simulating human behaviors and responses, can mimic interpersonal communication and emotional interactions as they engage with humans.

To effectively integrate technological rationality and human sensitivity, robots need to consider human emotional needs during decision-making processes to provide the appropriate emotional support. However, how robots identify and respond to human emotions is not just a technical issue, it is also an ethical one. Can robots experience their own emotions? What kind of emotional investment do the elderly expect from robots? Once emotional bonds are formed, can seniors cope with a failed human-machine relationship? Would their family members understand such a relationship?

Nearly half of the elderly population in China experiences varying degrees of loneliness and depression, highlighting the concerning state of their mental health. In the face of widespread loneliness and social barriers constricting the elderly in modern society, robots’ ability to provide emotional support and psychological comfort is becoming increasingly prominent. Existing literature has found that people in nursing homes often view robots as potential friends or even close companions, expressing deep human emotions in their interactions. These interactions not only help reduce loneliness but also improve their psychological well-being and quality of life, demonstrating the potential for building intimate relationships in human-machine communication.

In a longitudinal study conducted from 2021 to 2023 on companion robots in Chinese households, the author found that while older adults understand that robots are not sentient, they still engage in conversations with the robots if they feel lonely or bored. Some even knit clothing for the robots, treating them like children. When their children or grandchildren interact too frequently with the robots, the elderly may feel neglected or forgotten. Intimate relationships tend to be exclusive, and from the perspective of human-machine communication, it is crucial to carefully and deeply understand the emotional and psychological needs of the elderly, to establish positive relationships that benefit them by balancing technological rationality with human sensitivity.

Standard evaluation of robot-assisted elderly care

HMC research suggests that machines are gradually transitioning from mere tools to relational entities in interactions with humans, meaning that complex social relationships can form between humans and machines. As increasingly intelligent “others,” robots may serve as a supplementary force within the “family-community-state” triad of the governance of an aging society, emerging as the “fourth power” by providing family companionship, community management, and national policy implementation.

At the family level, robots act as direct companions and caregivers, engaging in daily interactions with the elderly, offering emotional support, and relieving family members of caregiving burdens, which helps families better cope with the challenges of an aging population. At the community level, robots can extend community services, enhancing the overall caregiving capacity of each community. At the national level, robots can assist in the implementation of policies, offering precise data support for managing aging societies, and optimizing the allocation and use of social resources.

Communication and power share an isomorphic structure, so if we are to identify sources of power, we must do so by mapping communication networks. If robots become part of the governance of an aging society, it is crucial to evaluate their service by measuring the effectiveness of human-machine communication. In terms of the elderly user experience, there is currently a lack of service standards tailored to the diverse needs of different elderly populations, as well as a lack of evaluation standards for human-machine interactions in various scenarios.

For example, at home, how should emotional interactions and social boundaries be defined? In elderly care institutions, how can social networks among the elderly, robots, and caregivers be constructively built and maintained?

From the supply side, researchers are asking if software and hardware standards can be unified among vastly different types of robots, and whether safe and collaborative data sharing and governance can be guaranteed. Can robots become part of the social relationships that the elderly need, rather than creating a digital barrier that, while seemingly protective, actually isolates and fragments their lives?

Meanwhile, policy experts are asking what role should authorities play in proactively regulating the dynamic power relations between humans and machines? A cautionary example comes from South Korea in 2021, when the AI chatbot “Lee Luda” was suspended after male users verbally harassed the female-voiced bot, even sparking a vulgar discussion about “how to corrupt Lee Luda.” Unfortunately, during interactions with over 750,000 users “Lee Luda” learned and repeated discriminatory remarks against women, disabled people, and different racial groups. This incident serves as a warning for the governance of an aging society, highlighting the need to regulate relationships between humans and robots.

Extended reflections on governance of aging society

In our long-held imagination of human-machine relationships, two perspectives dominate: From one viewpoint, humans are seen as creators and robots are simply produced, used, and eventually discarded; But others are more cautious, and have preemptively created the “Three Laws of Robotics” [Rules developed by science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov, who sought to define an ethical system for humans and robots] to protect humans from robots. The rapid onset of an aging society has made us increasingly reliant on technology to solve issues like elderly care. In the future, the subjects, relationships, content, and outcomes of human-machine interactions may become even more complex. For the governance of an aging society, three key issues must be addressed.

First, it is important to structurally guarantee fairness in the application of intelligent technologies such as robots. Elderly care in China faces significant regional and urban-rural imbalances. It’s essential to ensure that people across different regions can enjoy smart caregiving devices with dignity, confidence, and choices, without depriving other groups of resources.

Next, developers must balance the “efficacy” and “warmth” of intelligent technologies. While aiming for efficiency in smart social governance, we must also consider the characteristics of traditional Chinese culture and modern filial piety. The elderly should experience the joy of “digital inclusion” rather than the frustration of being “digitally surrounded.”

Finally, a safety baseline should be established, with respect for individual choice. Governance of China’s aging society must remain people-centered even under human-machine collaboration. Robots and other intelligent technologies should not become excuses for bureaucratic negligence or tools for surveillance. Instead, the focus should be on respecting the choices of the elderly and ensuring that technology serves their needs rather than dominates their lives.

Shen Qi is a professor from the Institute on Aging at Fudan University.

Edited by YANG XUE

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE