A unique facet of Chinese aesthetics

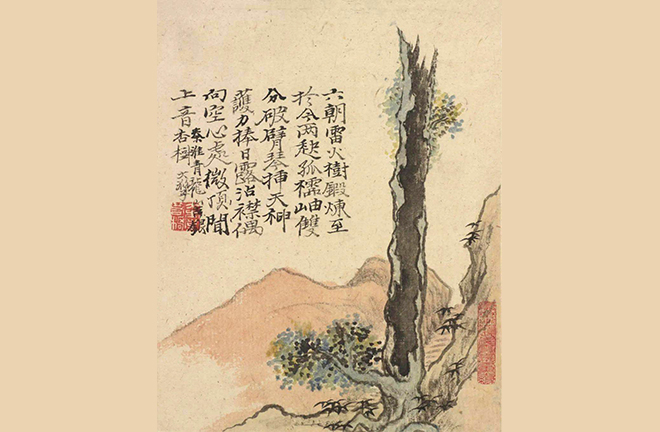

FILE PHOTO: “Reminiscence of Jinling” by early Qing artist Shi Tao

The aesthetics of traditional Chinese art have undergone a lengthy process of evolution, gradually developing into a unique aesthetic system. Within this tradition, there exists an aesthetic realm known as “transcendental beauty,” which embodies distinctive cultural connotations and aesthetic tastes.

The traditional Chinese understanding of beauty extends beyond outward splendor and attractiveness, placing greater emphasis on the spiritual and emotional realms. Consequently, traditional Chinese aesthetics tend to embrace inclusivity and transcendence, focusing less on superficial formal beauty and more on the emotions, meanings, and artistic conception conveyed by the artwork. For instance, withered trees, strange rocks, and wilted lotuses—though seemingly ordinary—can be endowed with a sense of beauty through artistic expression. This aesthetic concept, which transcends the dichotomy between beauty and ugliness, reflects a unique pursuit in traditional Chinese art that is not confined by conventional aesthetic norms but rather emphasizes the intrinsic meaning and spiritual depth that an artwork seeks to convey.

The beauty of resilience

Withered trees are a common and significant theme in traditional Chinese art, prominently featured in painting, poetry, and literature. Their branches, whether straight and towering or twisted and winding, convey a profound sense of formal beauty. The rough textures of their trunks, marked by the passage of time and life’s trials, reveal a striking charm rooted in strength and spiritual depth. These images can evoke a sense of vigorous vitality and reflect the enduring power of life.

The aesthetic value of withered trees occupies a unique and profound place in traditional Chinese art, symbolizing deep reflections on life, nature, and society. In Zhuangzi, withered trees are metaphorically likened to the human heart, highlighting the significance of withered trees in Taoism. The withered tree carries the implication of “practical value,” representing a state between usefulness and uselessness, symbolizing the Taoist understanding of life as free from the constraints of worldly society. This realm not only represents the calm acceptance of ageing naturally but also an easy grace in the face of difficulty. The image of the withered tree is closely tied to the Taoist philosophy of “the way of nature,” with its natural decline and resilient existence embodying the Taoist advocacy of governing or acting in a way that is in harmony with the natural flow of things. With its resilient vitality, a withered tree in its original form is the best interpretation of the Taoist aesthetic concept of “unity between heaven and humanity.”

Confucianism, on the other hand, attributes “virtue” to withered trees, expressing sentiments related to life’s hardships, the endurance of fate, and the attachment to homeland and country. The image of the withered tree becomes a vehicle for expressing reflections on life and fate, showcasing the human reverence and lament for life and nature. In the image of the withered tree the impermanence of life is revealed, along with the acceptance and understanding of fate—all deep philosophical explorations and reflections by ancient literati.

Ancient Chinese artists were known for vividly portraying withered trees. The Northern Song artist Guo Xi developed a style known as the “crab claw branch,” characterized by clusters of short, curving brushstrokes that resemble a crab’s claw. The trees he painted, with their twisted branches reaching skyward, represent the unceasing struggle against its fate. In his painting “Reminiscence of Jinling,” Shi Tao depicts an old ginkgo tree, hollow and broken, yet tenaciously standing tall in the mountains, showcasing its unyielding power. Through their depictions of withered trees, these artists expressed their admiration for vitality, as well as their reflections on the passage of time and the brevity of life.

The beauty of unrefined simplicity

Strange rocks, masterpieces of nature, sculpted by time, and marked by the earth, present a variety of shapes and peculiar forms. Their beauty defies traditional notions of beauty and ugliness, embodying a primal strength and rugged beauty. Whether they stand atop mountain peaks, lie by lakeshores, or hide deep within forests, they always exude a mysterious, detached aura that is suggestive of the majesty of nature.

In Chinese culture, the symbolic significance of strange rocks far exceeds their natural form. Influenced by Taoist thought, strange rocks are seen as manifestations of the natural essence, with their existence echoing the Taoist philosophy of “the way follows nature.” These stones, sculpted by wind and rain and polished by time, are generally believed to display a natural beauty that resonates with heaven and earth. In Confucianism, the hardness of strange rocks symbolizes noble character and steadfast will.

In traditional Chinese paintings, the depiction of strange rocks has evolved from meticulous fine brushwork to bold and freehand expression. In his painting “Auspicious Dragon Rock,” Emperor Huizong of Song depicted a dragon-shaped rock with meticulous detail and precision, creating a highly detailed and realistic image that exemplifies the court style of painting [The court style of painting during the Song Dynasty was characterized by its refined elegance, meticulous attention to detail, and a focus on both naturalism and idealized beauty]. The contours and textures of the rock are outlined with fine, strong lines and layered with ink washes, perfectly expressing its hard and moist texture.

In contrast to Emperor Huizong, the renowed scholar Su Shi depicted a strange rock as a chaotic mass in his famous painting “Wood and Rock.” The texture of the rock in Su Shi’s work seems to spiral like a vortex, featuring both square and round shapes that appear bizarre and ugly, while spinning rapidly. Some have suggested that Su’s approach transcends the limitations of traditional painting techniques, relying entirely on intuition and emotion rather than deliberately pursuing resemblance or adhering to established techniques. Consequently, Su imparted a sense of movement in his painting, reflecting the rock’s tenacious vitality. The strange rock was not depicted according to its physical form, nor is it purely imaginary. Instead, through subjective expression, the artist conveyed his concern with social inequality. Thus, the artistic portrayal of strange rocks evolved from mere natural imitation to a profound reflection of philosophical and emotional depth.

The beauty of desolate sadness

The lotus is an important theme in ancient Chinese painting, representing beauty, purity, and vitality. However, throughout history, many literati-painters have preferred to depict the lotus in a withered state.

The image of the withered lotus extends the symbolic implications of the lotus flower. It not only implies the ideal personality and spiritual pursuits of love, purity, sincerity, completeness, and vastness, but also evokes a corresponding beauty of tragic emotion. In the eyes of literati, the withered lotus is not just a natural phenomenon but carries rich symbolic meaning and aesthetic value—a profound reflection on the joys and sorrows, ups and downs of life. This beauty in decay inspired artists to think deeply about the essence of life, prompting philosophical explorations of fate, loneliness, and existence.

Withered lotus imagery is known as “ji zhao” [the illumination or clarity that arises from a state of tranquility, representing a form of inner enlightenment or wisdom that emerges from deep calmness], manifesting a supernatural aura in Chinese painting.

The withered lotus in Xu Wei’s painting, with blotchy dots and dripping ink, is visually striking and impactful, expressing tragic heroism that is both a display of the artist’s talent and an emotional expression of his frustration and tragic fate. In Zhu Da’s paintings, the lengths of the withered lotus leaves and stems are often exaggerated, embodying a resolute and noble demeanor with no trace of softness or coquetry. The artwork expresses a strong individual character, reflecting Zhu’s personality. Zhu poured his intense sorrow for his country into these paintings, which consequently convey a profound sense of detachment from the world and a melancholic, solitary mood. In Chen Shiceng’s “Autumn Lotus,” most of the lotus leaves are withered, with lotus stems broken and drooping, conveying a sense of sadness. The painting was created in memory of Chen’s late wife, and the entire composition is imbued with profound grief and sorrow.

In her later years, despite the torment of illness, the eminent 20th-century female painter Zhou Sicong frequently depicted withered lotuses in her work, into which she sought to incorporate her understanding of life. The withered lotus representations in her paintings subtly and reservedly express the artist’s feelings of sorrow, loneliness, and melancholy, while also presenting her own perspective on life as a transcendence of existence.

Artists express emotions such as loneliness, sadness, anger, or detachment through their depiction of lotuses. Withered lotus becomes a bridge connecting the artist’s inner world with the external world, reflecting their unique understanding of life, nature, and philosophical views on existence.

Wang Shuiqing is an associate professor from the School of Arts at Renmin University of China.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE