Significant clothing reformation during Ming, Qing eras

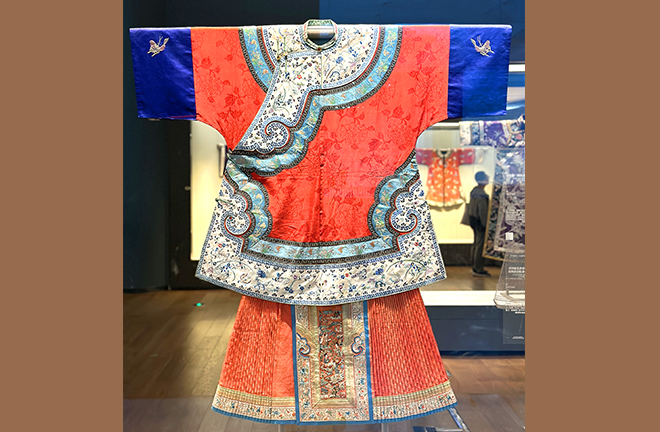

A red satin coat and a "ma-mian" skirt from the Qing Dynasty, preserved in Tsinghua University Art Museum Photo: Ren Guanhong/CSST

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) clothing retained the influences of the Han and Tang dynasties while introducing several new elements. For example, the popular “yesa” robe of the Ming Dynasty was derived from the Mongolian jisün robe commonly worn in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). A notable innovation in the mid to late Ming period was the introduction of the stand-up collar, which had not been seen in previous dynasties. Another distinctive feature of Ming-style clothing was the prominent lapel accessories, crafted from materials such as gold, pearls, and jade. The hierarchical system of Ming clothing became increasingly strict, with clear distinctions between the attire of officials and commoners, and detailed regulations governing the fabric, color, and patterns.

As the Manchus established the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), they introduced their distinct clothing culture. During the Qing era, Manchu and Han clothing cultures gradually merged, creating a unique Manchu-Han clothing style. This fusion represents the third major revolution in the history of Chinese clothing.

‘Conforming to regulation’

In the early Ming period, officials continued the traditions of the Tang and Song clothing, wearing fu-tou hats, round-collared robes, and belts with jade accessories, which became the framework of Ming official attire. Detailed regulations for ceremonial clothing were also formulated. The emperor’s regular attire in the early Ming included wearing the “yi-shan” crown (a black gauze cap with stand-up wing-like extensions on the back) and a collared robe adorned with circular dragon patterns.

The clothing of officials was distinguished by color according to their rank. Those of the first to fourth ranks wore scarlet robes, while officials in the fifth to seventh ranks donned blue robes. Green robes were designated for officials in the eighth and ninth ranks. Their regular attire also included “buzi” (embroidered insignia badges that were sewn onto the robes of Chinese officials) on the chest and back, featuring bird motifs for civil officials and beasts or mythical creatures for military officials, with specific designs varying by rank.

The empress of the Ming Dynasty usually wore a phoenix crown (often made from a cap-like base with a framework of precious metals like gold or silver), with a formal dress consisting of a large robe, a xia-pei scarf, and an inner garment. Her uniform was often embroidered with gold dragon and phoenix patterns. “Mingfu,” or women who held special status due to their familial connection with high-ranking officials or noblemen, were allowed to wear “di” crowns (“di” refers to pheasant, the rank beneath phoenix), with their regular attire also including “buzi” rank badges, determined by their husbands’ ranks. Compared to the Tang and Song dynasties, the clothing of common women in the Ming Empire became simpler overall. Typically, they wore jackets and skirts, with stand-up collars, wide sleeves with tight cuffs, and large pleated skirts, all distinctive features of Ming clothing. In addition to the pleated skirts inherited from previous dynasties, the “ma-mian” skirt (literally known as horse-face skirt, consisting of several rectangular panels, usually between four to six, with pleats on either side and the central part remaining flat) also appeared. The history of the ma-mian skirt can be traced back to the Song Dynasty’s “xuan” skirt, a functional skirt designed for women riding donkeys which became ubiquitous during the Ming Dynasty. However, the fabric, decoration, and color of the skirts were strictly differentiated according to social class. At that time, the term “ma-mian skirt” did not exist, and its style remained simple and unstandardized.

The third revolution in clothing

The Qing Dynasty required the Han Chinese men to adopt the Manchu hairstyle and attire, leading to the third major reformation of the traditional clothing system. Manchu clothing absorbed ritual elements from Han Chinese clothing, which were represented by auspicious motifs and colors, thus forming a unique Qing Dynasty clothing culture.

Qing officials’ court and ceremonial attire included headwear adorned with peacock feathers or other plumes, which indicated the rank and honors of the official. Feather ornaments were graded into “hua-ling” (made from peacock feathers), “lan-ling” (made of brown-eared pheasant feathers), and “ran-lan-ling” (made of dyed brown-eared pheasant feathers). Hua-ling headwear represented the most prestigious court rank, and the number of “eyes” or spots on the peacock feather—single, double, and triple “eyes”—indicated the sub-level of honor, with triple “eyes” being the highest.

Ceremonial attire for the emperor was known as gun-fu, an imperial attire worn over the emperor’s court robe, characterized by a round, azurite-blue collar and flat cuffs, embroidered with dragon motifs, with two badges symbolizing the sun and moon on the shoulders. The “buzi” badges on emperor’s attire were round, a design exclusive to the royal family. Court officials were only permitted to use square “buzi” badges. The motifs on buzi badges followed the Ming system of birds for civil officials and beasts for military officials. The “horse-hoof” sleeves were a distinctive element of Manchu clothing, characterized by their wide, flared cuffs, resembling the hooves of a horse. This design was both aesthetic and functional. The wide cuffs could be folded back for warmth or tied up for horse riding and archery.

During the Qing Dynasty, the clothing of Han Chinese women adhered to traditional Central Plains styles. Han Chinese women continued to wear shirts or jackets along with skirts or trousers. The Qing Dynasty “horse-face” skirt evolved from the skirts of the Ming Dynasty and gradually became everyday attire for Qing women. The horse-face skirt saw its most rapid development during the Qing Dynasty, forming a unique decorative structural style and becoming the basic form of Qing Dynasty skirts. The fashion trends of Manchu women did, however, possess their own distinct characteristics. Manchu women styled their hair in braids or buns, or in styles known as “liangbatou” (a distinctive hairstyle where the hair was divided into two large sections, resembling butterfly wings) or “dalachi” (this style involved creating large, wing-like shapes on either side of the head, often used for formal occasions). They wore the traditional “Qizhuang” attire, which included cheongsam robes (featuring a straight cut, high collar, and side slits) and sleeveless jackets or vests, paired with high-heeled shoes.

The Han-Manchu fashion persisted for over 200 years until the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing Dynasty and ended the imperial history of China. In the late 19th century and the early 20th century, Men gradually abandoned their long gowns and mandarin jackets, cut off their long braids, and began wearing Zhongshan suits or Western suits. Many women followed suit by cutting their long hair and adopting modernized cheongsams, which featured a more form-fitting silhouette and higher hemlines due to Western influence. This marked the beginning of a new and significant transformation in Chinese fashion history, symbolizing a return to trends of freedom and modernity.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE