Roger Fry illuminates Chinese influence upon Western art

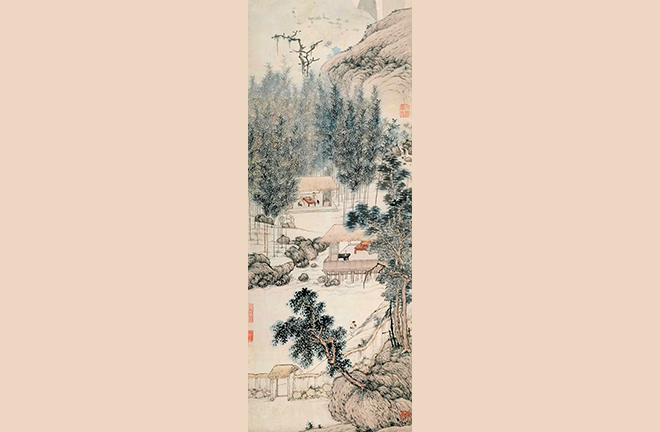

FILE PHOTO: A landscape painting by the Ming artist Shen Zhen

Roger Fry (1866–1934) stands out as a pioneer in the evolution of formalism in modern Western art. His aesthetic explorations bore the profound imprint of Chinese classical art. The manner in which he absorbed, interpreted, and adapted Chinese artistic principles vividly illustrates how Chinese classical aesthetics contributed to the development of Western Modernism.

Venturing into aesthetics

In his early years, Fry was deeply enamored with 15th-century Italian paintings and apprenticed under the American art historian Bernard Berenson. But rather than rigidly pursuing revivalism, he instead engaged in an exploration aimed at liberating art from convention and propelling it toward modernity.

The discovery of Paul Cézanne’s works in 1906 presented Fry with “a guide capable of leading them out of the cul-de-sac into which naturalism had led them.” His ongoing study of Cézanne helped Fry to gradually shape his formalist ideology, centered on the pursuit of “form,” “composition,” “structure,” “tone,” and “design” in visual arts. He believed that masters of modern art such as Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Henri Matisse successfully conveyed their spiritual experiences through these means, imbuing their works with the depth of imagined life. Classical Chinese art, represented by sculpture, painting, and calligraphy, epitomized the perfect fusion of formal aesthetics and spiritual pursuit, embodying a new direction in the evolution of modernist aesthetics. Thus, Fry’s aesthetic exploration was in resonance with his investigation into the Chinese art.

As early as the late 19th century, Fry’s interest in Chinese art began to blossom. In 1901, he attended an exhibition of Chinese art held at the newly built Whitechapel Gallery in London. He subsequently penned “Chinese Art at the Whitechapel Gallery” for the journal Athena, in which he contended that many pieces of the collection exemplified exceptional craftsmanship, sensitivity to materials, and a profound yearning for perfection, representing the pinnacle of Chinese artistic achievement. This marked his inaugural foray into the discourse on Chinese art.

As Fry delved deeper into his studies, Eastern art assumed an increasingly integral role as a reference point for his assessment of Western art, early African art, and the art of South African tribes. It became an increasingly indispensable cornerstone of his explorations into modernist aesthetics. In the serialized essay “The Munich Exhibition of Mohammedan Art,” published in The Burlington Magazine, Fry discussed the mutual influences between Eastern and Western art, as well as between Islamic and Chinese civilizations, asserting that the Near East and the West have, during important phases of artistic discovery and formal style development, evolved reciprocally, maintaining a close and harmonious relationship.

Between 1910-1911, Fry organized the first Post-Impressionist exhibition at London’s Grafton Galleries, themed “Manet and the Post-Impressionists.” Featuring works by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and other artists, it stirred up immense waves in Britain. The term “Post-Impressionism” thus entered the annals of modern art and art criticism, with Fry himself rising to a representative figure in the modernism movement in British art. In 1912, Fry curated the second Post-Impressionist exhibition, staunchly defending Matisse by arguing that “Matisse, in particular, aims at convincing us of his forms by the continuity and flow of his rhythmic line, by the logic of his space relations.” Fry noted that compared to other European artists, Matisse’s approach more closely aligned with the ideals of Chinese art. In 1919, Fry published his another aesthetic treatise, “The Artist’s Vision,” wherein he once again employed Chinese Song Dynasty porcelain as an example to illustrate the artist’s visual grasp of formal aesthetic elements.

Studies on Chinese classical art

The Burlington Magazine, co-founded and long edited by Fry, stands out as one of the earliest high-ranking Western journals to consistently feature substantial critiques of Chinese art. It also fostered an academic community dedicated to the study of Chinese art, comprising esteemed Sinologists such as Stephen Wootton Bushell, Laurence Binyon, Arthur David Waley, and Osvald Sirén.

In 1910, Fry predicted in The Burlington Magazine that “There are signs that the present rapidly increasing preoccupation with Oriental art will be more intense, and produce a profounder impression on our own views, than any previous phase of Orientalism.” In a book review of Binyon’s newly published Painting in the Far East, Fry contended that literati paintings from China’s Song Dynasty possessed “an extreme modernity.”

Fry’s view on Chinese Art

In his book titled Chinese Art, Fry aptly summarized the aesthetic qualities of Chinese art from three perspectives.

“The first thing... that strikes one is the immense part played in Chinese art by linear rhythm.” While European painting is indeed founded upon linearity, Fry observed that as Europeans’ observation of the external world became increasingly detailed and painters incorporated more elements from the material world in their depictions, “linear rhythm” gradually ceded ground to other considerations. In contrast, he believed that Chinese art never lost its linear rhythm as a means of expression. Painting and calligraphy are organically intertwined, constituting “a linear record of a rhythmic gesture,” and “a graph of a dance executed by the hand.” Fry maintained that the prevalence of “linear rhythm” permeates all facets of Chinese decorative arts, and is particularly evident in sculpture.

Secondly, Fry believed that rhythm in art almost always manifests as a flowing, unbroken quality. He argued that Westerners should have no difficulty recognizing this trait in Chinese art, as similar characteristics can be observed in many Italian works. “The contour drawing of certain pictures by Ambrogio Lorenzetti comes very close indeed to what we can divine of the painting of the great periods. Botticelli is another case of an essentially Chinese artist. He, too, relies almost entirely on linear rhythms for the organization of his design, and his rhythm has just that flowing continuity, that melodious ease which we find in the finer examples of Chinese painting. Even Ingres has been claimed, or denounced, as the case may be, as a ‘Chinese’ painter.” Thus, Fry discerned an inherent consistency between European and Chinese art in the expression of the artists’ inner passions.

Thirdly, Fry also drew comparisons of the shaping characteristics of Eastern and Western art, maintaining that the unique emotional quality of Chinese art forms stems from the distinct spiritual attributes of the Chinese people in contrast to European craftsmen. He stated that when the Chinese conceive of fixed forms, they begin with spheres, ellipsoids, and cylinders, whereas most European sculpture and painting, in terms of their creation of form, start from the cube or at least some simple polyhedron. By 1927, Fry further expounded upon the evolution of Cézanne’s style through an analysis of Chinese paintings’ formal concepts, producing the substantial aesthetic treatise titled Cezanne: A Study of His Development, in which he famously posited that Cézanne “showed how it was possible to pass from the complexity of the appearance of things to the geometrical simplicity which design demands.” Cézanne’s famous dictum, “Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone,” intriguingly parallels Fry’s characterization of Chinese art as deriving its forms from “spheres, ellipsoids, and cylinders.”

Of course, it must be noted that as a formalist aesthete, Fry explicated Chinese art from the perspective of formal analysis. As he put it, “A man need not be a Sinologist to understand the aesthetic appeal of a Chinese statue.” This view is undoubtedly open to debate. It seems that the imperialistic invasions by Western powers since the mid-19th century have instilled in Fry and other European and American modernists a sense of guilt and moral responsibility towards different cultures, leading them to hold Chinese art in high esteem and attempt to reconcile aesthetic and ethical tensions through a cultural globalism grounded in formal aesthetics. Indeed, overlooking the interplay between art and its cultural context hinders a comprehensive understanding of artists and their works. While Fry’s formal explication of classical Chinese aesthetics may not be flawless, he effectively integrated Chinese artistic concepts into the framework of Western modernist formal aesthetics, thus making an indelible contribution to the Eastern-Western literary and artistic exchange in the 20th century.

Yang Lixin is a professor from the School of Literature at Nanjing Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE