Long March

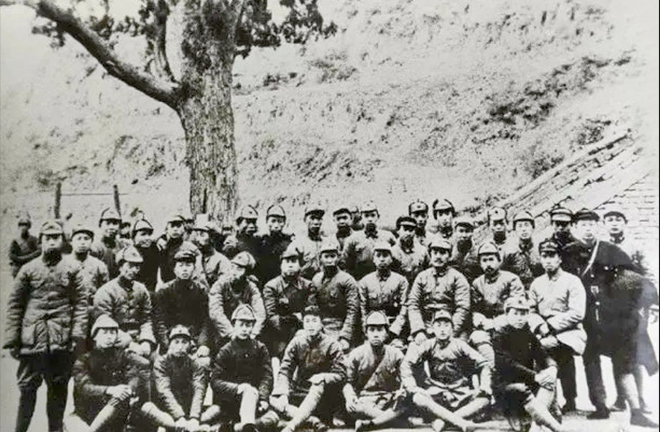

FILE PHOTO: A group of the Second Front Army arriving at northern Shaanxi after the Long March

On Aug 1, 1927, the Communist Party of China (CPC) led its first military resistance against the reactionaries of the Kuomintang Party (KMT). The troops led by Zhu De joined forces with troops led by Mao Zedong in Jiangxi in April 1928, forming the Fourth Red Army, the core force of the CPC-led military power. The Red Army thwarted four encirclement and suppression campaigns by the KMT between 1930 and 1933. However, as dogmatic “Leftist” leaders pursued an offensive policy and handed over command of the Red Army to Otto Braun, who had little practical understanding of China, the CPC failed to stop the KMT’s fifth encirclement campaign, which began in Sept 1933.

As the situation worsened in 1934, the Red Army decided to make a strategic shift. This monumental 12,500-km maneuver later became known as the Long March. In Oct 1934, the 86,000-troop Central Red Army set out from Jiangxi Province. Regrettably, approximately 50,000 soldiers perished in the battle of crossing the Xiangjiang River in late Nov and early Dec 1934. Confronted with this significant loss, the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee convened a meeting in Zunyi, Guizhou, in Jan 1935, which established a new central leadership under the stewardship of Mao Zedong.

Fighting the KMT forces in over 600 battles throughout their journey, the Central Red Army traversed 14 provinces, crossed 18 mountain ranges and 24 major rivers. Enduring desolate grasslands and snowy mountains, they ultimately reached Shaanxi in Oct 1935. Meanwhile, the other two major forces of the Red Army—the Second Front Army and the Fourth Front Army—converged in Garze, Sichuan, in July 1936 before proceeding northward together. In Oct 1936, the three major forces of the Red Army joined forces in Gansu, marking the end of the Long March.

The Long March was full of hardship. Faced with severe food shortages, the troops largely subsisted on wild herbs. When horses and other food sources ran dry, they resorted to boiling their leather belts and shoes to stave off hunger. While there exists no official record of the death toll, unofficial estimates put the figure at over 10,000 individuals. The valor and heroism attributed to the Long March inspired many young Chinese to join the CPC during the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE