Rural history reconstruction enriches Chinese culture

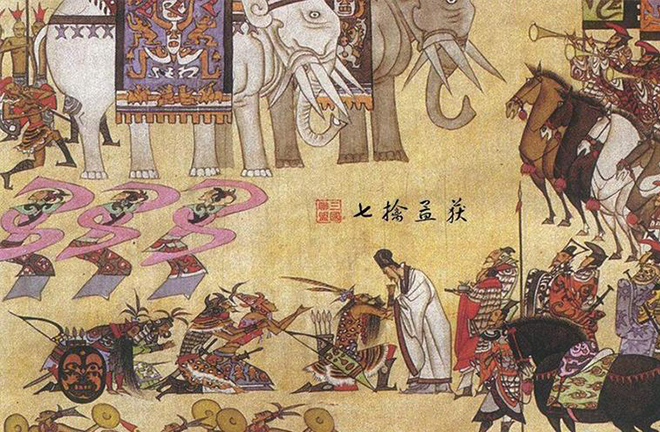

FILE PHOTO: The painting above portrays the capture and release of a rebel chieftain by renowned statesman and strategist of the Three-Kingdoms Period, Zhuge Liang. Legends say that Zhuge Liang caught and released Meng Huo, leader of southern rebel troops, seven times.

Ancient Chinese society had two types of history: history as science and history as culture. History, as science, aimed to restore objective historical facts and was written in accordance with the basic norms of traditional historiography. As culture, history involved storytelling and stemmed from cultural appeals. In this cultural practice, historical details were sometimes enriched and reconstructed—without disrupting the outline of major events—based on historiographers’ subjective imagination. In Chinese history, reconstruction of ancient rural accounts played an immense role in fostering history as culture.

Types of reconstruction

Documentation of history generally is a process of history reconstruction. The act of recording a document, according to the author’s description and evaluation of historical facts, represents an attempt to reconstruct history. In traditional eras, historical studies primarily focused on grand narratives, analyzing the merits and demerits of emperors, generals, and ministers, who were divorced from the lower strata of society, and on whether government policies were right or wrong. The narratives were presented as official history or officially printed history books.

However, these official documents usually only provide a grand historical account or space, with little attention to the details of life in rural China. This highlights a need to supplement and enrich historical narratives and their spatial construction in research of rural China. In this process, researchers often resorted to speculation or fabrication, in addition to using objective facts. This is what reconstruction of rural history is about in this article.

Reconstruction of history can be divided into four types: retelling of stories about worthy historical figures, specification of historical events or systems, refinement of names of locales, and repositioning of hills and rivers.

Retelling stories about worthy historical figures was usually to re-specify the tales of native figures or those who had been to the village, making details an important part of rural history. For example, stories about famous figures such as legendary Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–c. 1600 BCE) founder Yu the Great, renowned statesman and strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (220–280) Zhuge Liang, general of the Three Kingdoms Period Guan Yu, and Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) writer and calligrapher Su Dongpo (also known as Su Shi) are ubiquitous across China, many local dishes are named after Dongpo or Zhuge, and their mythos is entwined with culinary histories. Though not always credible, these myths are still just as significant to history as culture.

Historical events and records of systems were often specified under the principle of “retaining key facts regardless of minor information,” which is also a guiding principle for historical fiction writing. For example, based on the historical fact of Zhuge Liang’s expedition to the south of China, the famed historical fiction Romance of the Three Kingdoms made up a story that Zhuge Liang captured and released Meng Huo, rebel chieftain of southern “barbarian” troops, seven times. In so doing, Meng Huo, who was factually of the Han ethnic group, was reshaped as an ethnic minority leader, and Zhuge Liang’s deed of winning over his captive by dint of virtue was widely circulated as a folktale. Even now there are many Meng Huo towns or temples in southwestern China.

Refining the names of historical locales is also part of rural history reconstruction. In Chinese history, locale names have strong cultural functions apart from their basic function of identifying a location. Conjecturing in toponymy often reflected cultural appeals, and intermingled with history as science. Not only did rural unversed scholars fictionalize rural history, but many prestigious historians also speculated connotations of place names for rural history reconstruction.

For example, in southwest China’s Chongqing Municipality, there is a place called Hugui Shi, literally meaning “Summoning Home Rock.” Locals believe it is related to the tale of Yu the Great, who left his home to help control flooding shortly after his wedding. Later he passed by his home three times and didn’t once enter, so his wife stood on a rock and tried to summon him back home. In history, the rock was also colloquially known as Wugui Shi (Turtle Rock) because its shape resembles a turtle. The evolution of the place’s name from a colloquial one into a culturally connoted name is a result of history reconstruction by generations of rural scholars.

Repositioning hills and rivers is another crucial type of rural history reconstruction. In ancient China, people’s knowledge of geographical spaces was loosely a “conception of virtual spaces.” For example, the position of hills or rivers was understood by “the number of li (a unit for measuring distance)” north, east, west, or south between one visual marker and the object in question. If a hill or river had no obvious and unique cultural and natural symbols, it was difficult for later generations and non-locals to accurately locate the place. In times of social turmoil, many place names were not inherited, leading many passes, mountains, and postal stations to be repositioned or reconstructed in spatial memory.

Paths of reconstruction

In general, reconstructed rural history was buttressed by a larger, fact-based historical background, and reconstruction paths include fabricating oral legends, textualizing oral tales, and adding landscapes to oral and textual stories.

Fabricating oral legends is rural history reconstruction at the lowest level. In ancient China, almost all early historical accounts were passed down through word of mouth, such as those concerning the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. Many oral legends are still prevalent in rural areas today. There is the popular folk tale that Zhuge Liang captured and released Meng Huo seven times, but in southwest China’s Yunnan Province, a different legend circulates, countering that it was Meng Huo who captured and released Zhuge Liang seven times. All these stories were not documented until recently.

Textualization of legends became more common in the later stage of traditional society. Many long rural histories were written down in local chronicles, genealogy registers, manuscripts, and tablet inscriptions. Text records are usually regarded as more credible. For example, a folk nursery rhyme concerns the legend that late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) rebel leader Zhang Xianzhong sank an enormous amount of gold and silver treasure to the bottom of the Minjiang River in southwest China’s Sichuan Province. The rhyme says that finding this treasure would be enough to buy the whole of Chengdu, capital of Sichuan. This rhyme was widespread in many parts of Sichuan and has been adapted into several texts.

Adding landscapes to oral and textual stories has become the most important aspect of reconstructing rural history, but it is also the most deceptive path. Landscapes are believed to be more convincing than text records; those with a long history, in particular, are even more trustworthy. Therefore, many toponymic sites like Zhuge Tai (Zhuge Building) and Dongpo Jing (Dongpo Well), and names of objects or foods containing stories, such as Zhuge Cai (Zhuge Cuisine or Corychophramus Violaceua) and Dongpo Rou (Dongpo Pork), are considered irrefutable proof of true history.

Telling true from false

In ancient China, complicated factors influenced rural history reconstruction, so the authenticity and scientific nature of reconstructed history vary from one version to another. Imagination in reconstruction can generally be divided into objective speculation and subjective fabrication. Objective speculation is when historians reconstructing rural history were not aware of their bias or made honest mistakes due to gaps in knowledge or technical conditions, as in the case of repositioning toponymic locales. Subjective fabrication occurred when historians made up stories deliberately, either to supplement political appeals in ancient states, identify with the nation, which predominantly revolved around the Han ethnic group, or to publicize local officials’ achievements.

From the perspective of political appeals, rulers of ancient states abolished many illegitimate or irregular sacrificial practices on the local level and appointed officially recognized idols for sacrifice, such as Guan Yu and Zhuge Liang. In rural China, the most important cultural orientation was to integrate into the Han-dominated Chinese nation, so fictionalizing stories about their worthy rural predecessors and incorporating historical figures of the Han ethnic group into local history was a crucial approach to building the national identity.

However, in Chinese history, many stories passed down from generation to generation were, in fact, true history. Their absence from historical records often wove them into many fabricated, conjectured stories, making it hard to untangle the true from the false. For example, Zhang Xianzong’s tale of burying treasure, though not documented, was proven true through archaeological excavations.

Historians shoulder the heavy responsibility of differentiating fictitious stories from true oral accounts. In Chinese rural history reconstruction, oral fictional tales, once including landscapes, were likely to gradually be acknowledged as “true” history, especially after the stories spread to other regions and passed the test of time, thus impacting contemporary understandings of history and misleading people to argue over such issues as the correct hometown of certain historical icons.

In contemporary rural society, many fictional legends, particularly those supported by historical landscapes, have no linguistic symbol of “legend,” so people subconsciously believe they are true.

Historians are first responsible for distinguishing history as science from history as culture in rural history reconstruction, in order to enhance the credibility of history as science. It is therefore necessary to strip elements of reconstruction from disordered historical phenomena, to try to reveal the original, true historical scenes.

Second, legacies of history (as culture) that have been passed down through generations cannot be overlooked, because these legacies bore witness to changing cultural backgrounds in different historical eras and are vital historical and cultural resources that should be respected.

Third, historians should guide and regulate current rural history reconstruction practices to highlight fictional and fabricated stories and draw a clear line between history as culture and history as science.

Lan Yong is a professor from the School of History and Culture at Southwest University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE