Respect for scholarship is a shared value in China and the West

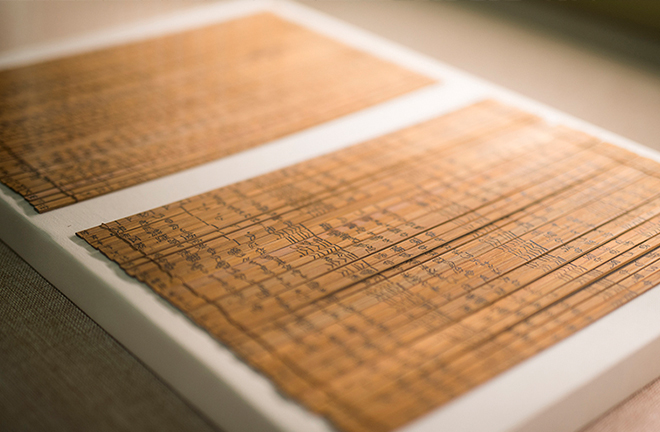

Bamboo slips dating to the Warring States Period housed at Tsinghua University Photo: TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM

The developments in our turbulent time call us to reexamine commonalities between Chinese and Western culture. There are universal commonalities shared by all cultures, such as caring for children and the elderly, valuing life, and being charitable to relatives and friends. This is not what is going to be discussed here. There is another, less universal and more interesting value shared by China and the West. It is their common respect for scholarship and a willingness to invest resources in the preservation and advancement of academic traditions.

In both Chinese and Western societies, historical experience and scholarly knowledge provide authority that is essential when seeking solutions to contemporary problems. In these societal systems, the professional production of knowledge is closely related to statecraft and governance. This ensures that most important decisions have to undergo professional scrutiny before being adopted. Dangerous opinions which don’t conform to historical experience and academic consensus will most likely be rejected, ensuring safety and continuing existence of the society in general. Respect for professional expertise is a deeply ingrained shared value in Chinese and Western culture. It is easy to disregard such commonly shared views and take them for granted. However, their formation was a long complex process, and it is worth reflecting on how it unfolded in both societies.

Origins of scholarly tradition

Around the 5th century BCE, China underwent major historical changes. The development of iron metallurgy fueled population growth and urban expansion, bringing about rapid changes in the social system, when hereditary aristocracy started to be replaced with bureaucrats in state governance. This historical environment produced the extraordinarily creative and diverse debate of the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE), which still constitutes the bulk of Chinese philosophy textbooks.

At this time, thinkers with different intellectual tendencies were no longer willing to speak for aristocrats, offering up independent voices instead. They represented a new stratum of shi 士 (men of service or scholars). Most of them were not wealthy, but they had access to education, were passionate about their studies, and eager to participate in government.

At that time, the shi did not enjoy a very high social status. Nonetheless, their professional reliance on the written word and belief in its transformative power put them in charge of the production and transmission of China’s written record. By the later part of the Warring States Period, almost all of China’s history was profoundly influenced by their ideals.

To give one example of this influence, notable rulers in Chinese historical imagination are almost invariably accompanied by wise ministers. For example, Cheng Tang, founder of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), is associated with his educated advisor Yi Yin; likewise, the success of kings Wen and Wu, founders of the Western Zhou State (c. 1046–771 BCE), was determined by the assistance from Dan, the Duke of Zhou, and Jiang Ziya, the Grand Duke, who were not only ministers, but also scholars. Monarchs’ reliance on scholars is a common trope that runs through Confucian, Mohist, and Taoist texts, and it can be considered part of the intellectual consensus of the Warring States Period.

Embedding the images of scholars into key moments of history may be the most important contribution that the shi of the Warring States Period made to Chinese social consciousness. Due to their significant influence over the creation of collective memory, they were thus also able to contribute to the shaping of the future.

In the Tsinghua University Warring States Bamboo Manuscripts, excavated and published over the last two decades, there is an interesting text mapping out the blueprint for social reform. The text consists of two manuscripts, which constitute a single continuous composition despite being known separately as “Zhi zheng zhi dao” (Way of ordering government) and “Zhi bang zhi dao” (Way of ordering the state). “Zhi zheng zhi dao,” which was published in the ninth volume of the Tsinghua bamboo manuscripts, is the beginning of the text, while the “Zhi bang zhi dao,” published in the eighth volume, corresponds to its final part.

By juxtaposing the idyllic past with the corrupt present, this text systematically elaborates on a way to return to the social order pioneered by the sage rulers of the past. The content of the text is not entirely new, and many details can be seen in well-known philosophical collections like the Mozi, the Mengzi, and the Xunzi. However, in most of these texts, the vision of an ideal society is scattered across different chapters and a variety of contexts. In contrast, the excavated text provides a comprehensive description of a social reform, which enables us to view the social ideal of the Warring States shi from a holistic perspective. The ideal society of the sage rulers from remote antiquity described in the text does not correspond to historical past, but rather embodies the authors’ dream, their imagination of a better governed future society.

The authors of the text pointed out many problems that threatened the society at their time, such as expansionist foreign policy; attaching too much importance to military merits; dismissing the opinions of worthy officials by the ruler; employment of high-ranking officials based on candidates’ aristocratic origins or the ruler’s personal preferences as opposed to talent and merits; influence of superstitious practices on political decision making; and insufficient attention to people’s wellbeing.

To solve these problems, the authors argued that the ruler should first of all embrace a belief in his subjectivity. The success of governance depended on the soundness of policies, and not on the whims of Heaven or other superhuman entities. Liberating from superstition was thus the premise for responsible governance and a professional bureaucracy. In such a social system, educated men of service are not passive instruments for accumulation of knowledge and experience–they are active participants in social management, a power that makes the state system more professional, moral, and self-conscious.

The blueprint for social reform presented in “Zhi zheng zhi dao” and “Zhi bang zhi dao” is not merely a theoretical construct, but a credible reflection of the transition from the aristocratic style of governance, coupled with elements of superstition and martial excess, to a bureaucratic style that characterized the Chinese state system after the Warring States Period.

Despite numerous political transitions in Chinese history, men of service who inherited and transmitted scholarly traditions from the past always enjoyed a high status in society. Today, the ideals of the Warring States shi, commonly assembled under the umbrella of “Confucianism,” still persist in China’s academic community and administrative practice. Although the system has changed, the ancient idea of a symbiotic relationship between politics and scholarship has never disappeared.

Secularization in Europe

It may seem that texts from China’s Warring States Period are only useful for the study of Chinese history, but not relevant to the contemporary world that has been profoundly influenced by Western civilization. In fact, the changes that Europe underwent in the modern period in the 16th to 18th centuries bear resemblance to social transformations reflected in “Zhi zheng zhi dao” and “Zhi bang zhi dao.” In his 2007 book A Secular Age, Canadian scholar Charles Taylor offered a detailed account of Europe’s development from an aristocracy-dominated society that attached high importance to military achievements into a “polite” secular society. Among the thinkers who contributed to this secularization, many were firm Christian believers, and they didn’t advocate for the abolition of religion. Instead, they called for accepting human responsibility for the world and emancipating human subjectivity, while addressing social problems, including the critical issue of war and peace, by rational means.

Similar to Chinese people in the Spring and Autumn (770–476 BCE) and Warring States Period, Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries woke up to the importance of easing conflict through peaceful approaches after lasting and ruinous wars. The process of secularization led to a comprehensive transformation in the world outlook: in place of a vision where God bears responsibility over day-to-day affairs comes a vision where the main responsibility rests on human shoulders, while God assists his creations indirectly and from a distance.

This process of disengaging from a world vision saturated with mythological elements, dubbed “disenchantment,” can also be seen in China during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period. Such early texts as the Venerated Scriptures (Shang Shu), and the Zuo Commentary to the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu Zuozhuan) include many examples of a belief that the survival or collapse of states was determined by Heaven and spirits, and the role of humans was only restricted to passive acceptance and cooperation. This is precisely the view countered in “Zhi zheng zhi dao” and “Zhi bang zhi dao,” which argues that state affairs are the responsibility of the ruler, while sacrificial and divinatory activities shouldn’t play a decisive role.

Influence of Chinese philosophy

The similarity between the secularization of European society during the modern period and the social transformation in the Warring States China 2,000 years earlier is not only a historical coincidence, but, to some extent, the result of a cultural influence. The transformation depicted by Taylor took place when European Jesuit missionaries began to systematically study China. Their works on Chinese political philosophy and social system, as well as their translations of philosophical classics, drew great attention in Europe at that time.

In the late 17th century, renowned German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz acquired much information about China by reading the works of Jesuit missionaries and communicating with them through correspondence or face to face. He spoke highly of Chinese “practical philosophy” reflected in the organization of state and society. He proposed the establishment of a bidirectional “mission,” which would not only spread European ideas to China, but also encourage Chinese “missionaries” to advance the “practical philosophy” in Europe. Leibniz’s ideas are an example of how China’s social system, with its emphasis on professional administration, provided an important point of reference for the reform of European society during the modern period.

Although the secularization of European society followed its own development logic, exposure to China deepened Europeans’ trust in rational management. Over the centuries that followed, close contact has drawn China and the West closer, fostering many common values. When observing different cultures, we often pay attention to fascinating differences, while the worthwhile commonalities largely escape from our view. The mutual convergence has made us less aware of the role that others have played in the shaping of our own culture. Responsible and rational management of society based on the respect towards professional expertise is a common value that Chinese and European societies have obtained at different times, but at a similarly high price. This shared value is an example of the symbiotic development of our cultures, and also one of the key reasons why we can still look at the future with optimism.

Yegor Grebnev is a distinguished associate research fellow from the Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences at Beijing Normal University at Zhuhai, and an assistant professor of Chinese culture and international communication at Beijing Normal University–Hong Kong Baptist University United International College.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE