Xu Zhimo drawing inspiration from where he walked past

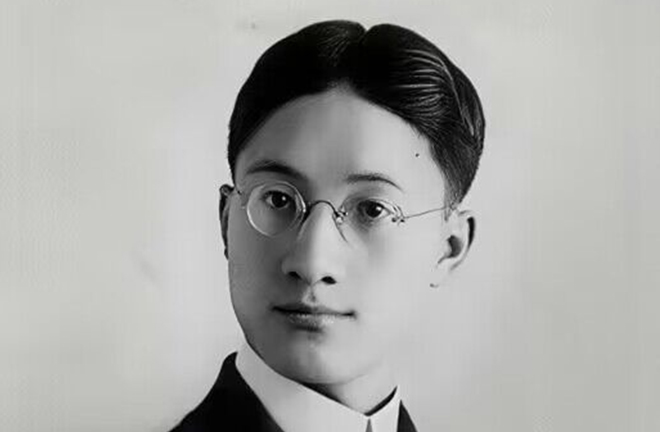

FILE PHOTO: The celebrated Chinese poet Xu Zhimo in his youth

In his work of prose titled “Self-Dissection,” the Chinese poet Xu Zhimo (1897–1931) wrote of his active nature and fondness for observing things in motion, believing movement stimulated his breathing and added to his vitality. As a young student, Xu harbored a soulful commitment in traveling. His journals included several copies of the travelogues of others, and he specifically devoted a section to “places visited,” in which he recorded his daily excursions to local scenic spots. In August 1918, at the suggestion of Liang Qichao and the support of his father Xu Shenru, Xu left China to study in the United States. To follow his spiritual mentor Bertrand Russell, he transferred to the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1920, and subsequently pursued studies at the University of Cambridge, where he penned numerous popular masterpieces.

Western influence

Xu Zhimo is often introduced to most through his melodious and elegant poem “Taking Leave of Cambridge Again.” His time at Cambridge from 1921 to 1922 greatly influenced his artistic perspectives, contributed to his spiritual growth, and established “freedom” as the core of his inner pursuit. Xu held a deep affection for Cambridge, and in June 1928, during a sentimental revisit, he penned the poignant lines: “Softly I am leaving,/ Just as softly as I came;/ I softly wave goodbye/ To the clouds in the western sky” (trans. Guohua Chen). The elm trees, golden willows, green tape grass, and the pool he immortalized in his poetry can still be found today by the serene River Cam.

Embarking on odysseys through the British Isles, wandering the vast expanse of Soviet lands, forging connections across the European continent, and traversing the landscapes of India and Japan…The enchantment with the act of “journeying” adorned every chapter of Xu’s life. He extensively delved into world literature, drawing inspiration from the poetic art of luminaries such as George Gordon Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, and Robert Burns, nourishing his poetry with the cultural essence of English-American Romanticism and Aestheticism. His interactions with renowned literary figures, including Bertrand Russell, Thomas Hardy, Rabindranath Tagore, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, and Kathleen Mansfield Murry, left a profound impact on him. His encounter with Mansfield especially inspired Xu’s pursuit of ideal beauty, while meeting Dickinson played a pivotal role in Xu’s turn from politics to literature. While introducing Chinese literary classics to the world, Xu also translated the works of many foreign luminaries, making great contributions to the integration of Chinese and Western cultures.

Xu regarded pure truth and free beauty as the ultimate goals of art, with love and idealism as the core themes in his literary world. The Chinese writer Hu Shi once described Xu’s outlook on life as “truly a kind of ‘simple faith,’ which contains only three major characters: love, freedom, and beauty.” His life consisted of the pursuit of this simple faith. In the poem “The Joy of a Snowflake,” Xu likened himself to a “flying snowflake,” while the protagonist in “In Search of a Bright Star” rides a “blind limping horse” into the dim night, ultimately falling in the vast wilderness. The bright star the author sought could symbolize love, or any other valuable and meaningful pursuit in life.

Embracing nature

Xu was “a child of nature.” In his childhood, he ran freely through the fields, gazing at the clouds in the clear sky, and indulging in one fantasy after another, even yearning to transform into a cloud and soar above the firmament. Throughout his writing career, he consistently urged people to “pulse in unison with nature.”

From the elegance and tranquility of nature, Xu derived fresh insights. He viewed the exquisite natural scenery as a source of thought, and believed that life’s pessimism stemmed from the disconnection between humanity and nature. Consequently, he coined a new term, “Duyou Zhiyu,” or “solitary roaming,” advocating for individuals to wander alone amidst nature. In essays such as “Peilengcui Shanju Xianhua” [“Idle Chats at the Mountain Residence in Florence”] and “Wosuo Zhidaode Kangqiao” [“All I Know About Cambridge”], Xu frequently highlighted the benefits of being “alone” or “solitary.” He even believed that the moment when a person roamed alone in nature was when the body and soul acted in harmony, akin to a child rushing into a mother’s embrace. The path of solitary roaming represents the path to self-discovery for modern people. Understanding Xu’s concept of “solitude” is the key to fully appreciating his poetry and prose, shedding light upon his carefree and light-hearted demeanor.

Inheriting classical traditions

Travelling bestowed upon Xu a mosaic of unparalleled experiences, gifted him a unique literary romance, yet it is equally important to acknowledge that he also inherited the legacies of Chinese classical culture. Starting at the age of five, he received a rather comprehensive education in classical literature in a traditional private school. His solid foundation in classical Chinese literature paved the way for his later writing.

Xu’s Eastern aesthetic perspective on nature inspired him to dedicate a significant portion of his writing to depicting nature in his prose and poetry. He frequently portrayed traditional imagery such as “moon” “willow” “rain” “plum blossom” “night” and “dusk,” delving into their soft and mysterious nature, constructing a world of imagination brimming with intense emotions. He reflected on the relaxation of people in nature and expressed nostalgia for his homeland and a sense of wandering through the use of nature imagery, akin to how the ancient Chinese literati expressed themselves. These clusters of imagery serve as metaphors for Xu’s existential condition. He had a particular fondness for using imagery associated with “spring” and “autumn,” corresponding to the traditional sentiment of the ancients, who “grieve over the passing of spring or feel sad with the advent of autumn.” Nearly 30 of his poems feature imagery of autumn. The poetic sentiment he distilled from the autumn hues bore the contemplative mood of travel and homesickness, as well as the unconventional grace of returning to nature, reminiscent of Tao Yuanming (365-427), a noted poet who led the life of a recluse.

To reach the aesthetic realm of classicism, Xu seldom paid attention to the material life of modern people, nor was he willing to portray the landscapes of urban civilization. His emphasis on expressing classical sentiments over novelties reflects the profound influence of literary traditions on the psychology of writing of the writers from the New Literature Movement. In Xu’s case, the “inheritance” of classical Chinese literature and the “transplantation” of foreign literature was not contradictory. He often grafted classical aesthetics onto the realities of life, seamlessly integrating traditional imagery and imported symbols with his modern sensibilities, with the aim of presenting the purity of human nature, the harmony of aesthetics, the clarity of the soul, and the robustness of life. The classical traditions of lyricism and imagery, after the writer’s emotional processing, acquired new meanings and achieved a unity of “romantic” and “classical.”

Unrestrainedly traveling between Chinese and Western cultures, being exposed to both classical Chinese and foreign literature, and exploring the linguistic characteristics of native Chinese speakers—the features that Xu’s literature presents have become effective ways for people to decipher his “literary code.” Imagery such as the “bashful water lily that could not withstand the cool breeze,” the oriole that is “as passionate as spring, as flame,” and the fallen leaves that “haunts my dreams” enriched the imaginative world of new literature. Xu consciously turned towards cultural traditions, reconstructed them with modern thinking, and blazed a new trail that connected the traditional with the modern. He stepped from traditional Chinese culture to the world, surveying the colorful customs of foreign lands, and then shifting from romanticism to classicism, injecting contemporary Chinese literature with the essence of classicism. This was Xu’s choice, and perhaps, a potential inspiration for the future development of literature.

Lu Zhen is a professor from the School of Literature at Nankai University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE