The development of science fiction in modern China

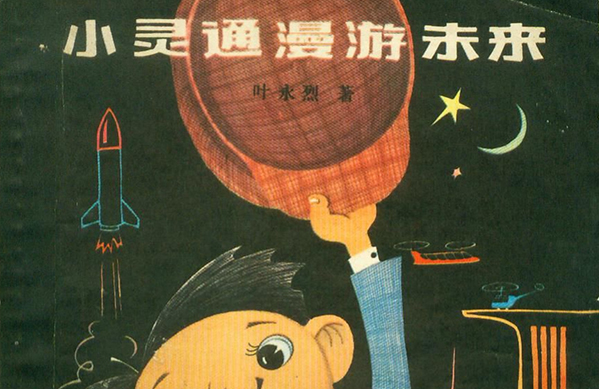

FILE PHOTO: The cover of Little Smart Wanders in Future by Ye Yonglie, published in the 1970s

Chinese science fiction drew inspiration from the enlightenment ideals of the early 20th century, as well as the concept of “scientism” that had not been extensively explored. In the late 1970s, Chinese science fiction writers found themselves at a crossroads. Their writing depicts the complex emotions experienced as they navigated this complex landscape.

Early exploration

In the past, science fiction had been backed up by the grand narrative system of science popularization, from which it derived its validity. However, after more than half a century, this validity began to be seen as a constraint. Neither theoretical discussion nor practice at that time offered an effective solution to this problem. For example, Ye Yonglie, renowned for his science fiction story Little Smart Wanders in Future, grew exhausted responding to the widespread criticism of the “pursuit of fame and fortune” and “excessive marketization” throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Despite the efforts made by these authors, Chinese science fiction had not completely broken the stereotypes established by Little Smart Wanders in Future, at least at that time. What is really worth noting is the inner pursuits of these science fiction writers—“We deeply feel the weight of history on our shoulders” (Tong Enzheng’s “Expression in Spring”). Their enthusiastic exploration and reflection, as well as the pursuit of science, fantasy, and the future of human beings, have affected generations of readers. Liu Cixin, author of The Three-Body Problem, calls himself “the first generation of science fiction fans.”

Barriers to prosperity

In 1902, Liang Qichao defined “science novel” for the first time. However, his proposal quickly lost traction despite going viral. This pattern repeated itself multiple times, resulting in science fiction being consistently neglected after enjoying a brief period of popularity, for several reasons.

The first reason was that the validity of “fantasy” had not been fully demonstrated. This posed a challenge for Chinese science fiction. For a long time, discussions surrounding science fiction often portrayed “fantasy” as the antithesis of what should be emphasized. In scientific contexts, “fantasy” was labeled as “sub-science” or even “non-scientific” literary fiction. In literary contexts, “fantasy” was seen as “non-realistic,” or even close to “absurdity” or “escapism.” During a discussion on Chinese science fiction in the 1990s, Wang Furen pointed out that the Chinese culture has a tradition of “emphasizing reality over fantasy,” and that fantasy cannot be put into practice unless it is “transformed into the will to affect reality.”

Another reason was that the popularization of “science” was still in its exploratory stage at that time, which significantly restricted people’s acceptance of science fiction. Only when science becomes a part of daily life is it possible for the public to appreciate it. This was why early science fiction writers had either worked in the front lines of scientific research or had long been engaged in careers close to the frontiers of science and technology. In 2023, famous film director Guo Fan said in an interview that the success of “The Wandering Earth” film series is closely related to China’s aerospace technology and other major scientific breakthroughs. In this sense, the prosperity of science fiction is inevitably related to the level of modernization of a country, region, or nation.

The final and perhaps most fundamental reason is that the development of science fiction is an essential part of the ongoing evolution of human culture. Without the ability to envision a future world that truly encompasses China, other developing nations, and humanity as a whole, there would be no fertile ground for Chinese science fiction to flourish. When submarines are commonly used in military, Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea seems less futuristic. When the Internet became basic infrastructure in cities, “cyberpunk” began to decline. The most imaginative science fiction writers are nothing more than a group of perceptive individuals in the process of modernization. They craft stories on the cusp of a new era, fully aware that the only constant in the age of science and technology is perpetual change.

Local characteristics

Currently, science fiction themes with strong local characteristics are gradually forming a new tradition and demonstrating their influence.

Chinese science fiction writers basically gave up panoramic depictions of ideal social systems and sci-tech development after creating a small number of utopian stories in the late Qing Dynasty. The young writer Lu Xun was keenly aware that a perfect, static future can’t exist. He wrote that even in a future world where interstellar colonization is commonplace, conflicts still exist. Afterwards, in works about the future, Chinese science fiction writers often focused on how to “reach” the future through scientific approaches. Science fiction thus serves as a form of compensation for the dissatisfaction experienced with the present reality. Similar works have also appeared in some former colonies or third world countries in South America and Southeast Asia. These works can break away from the grand narrative often seen in Western science fiction, and describe a future where differences and opportunities coexist.

Science fiction imagination based on Chinese history and mythology has existed since the late Qing era. However, after nearly a century of exploration, a group of young authors in the 1990s proposed the phrase that “there are no glazed tiles on Mars” [Since Chinese traditional buildings are often covered with glazed tiles,this phrase indicates that one becomes part of the overall collective called “humanity” when going into space, and is no longer Chinese, American, Russian, etc]. They express that many previous works of science fiction are merely simple borrowing and patchwork, wasting traditional cultural resources and deviating from the spirit of modern science. However, in recent years, science fiction inspired by Chinese history and mythology have been popular among overseas Chinese writers, inspiring several influential works, such as Ken Liu’s Good Hunting and Xiran Jay Zhao’s Iron Widow, which are generally classified as the genre known as “Silkpunk.”

Jiang Zhenyu is an associate research fellow from the College of Literature and Journalism at Sichuan University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE