Silence valuable in oral history

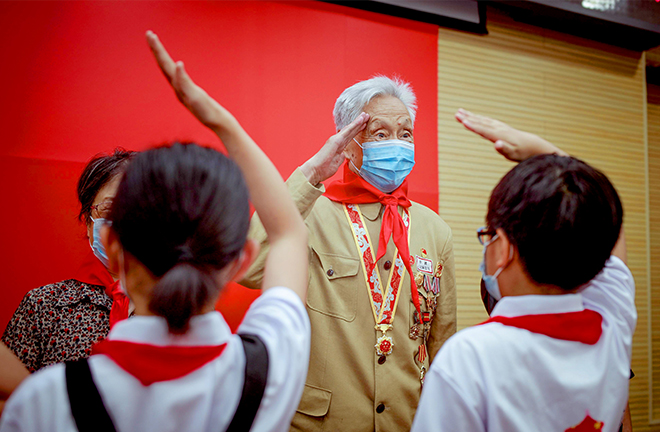

Young pioneers salute veterans at a book release in Dongcheng District, Beijing, where a memoir with recollections from 22 veterans was published, telling stories of how they fought for the honor of the country. Photo: CFP

In recent years, the disciplinary integration and paradigm innovation brought by oral history research have rallied academia and achieved remarkable results. When many scholars embark on field investigations to collect memoirs and reflect on the academic value of oral history, a key methodological problem stands out—how do we capture silent memories?

While oral history exemplars are filled with “perfect oral narration,” some complicated silent moments are left out. Often, rather than fluency, conversations are full of pauses. Rather than complete, they are fragmented. And rather than coherent, they are fractured. The filtering and weighting of time, the embedding and disembedding of space, the presence and absence of power, and the flow and shaping of culture make these episodes silent memories. How we should interpret these negative spaces is thus worth deeper thought.

Underrated value of silence

Between questions and answers, there are the different types of speakers. When the field becomes the stage and the people step into the center, the curtain of oral history is slowly opened. Between questions and answers, some memories emerge clearly with the superimposition of different narrations, while others remain blurry, absent, or completely lost in boundless silence.

For the sake of academic research, scholars expect feedback to the questions proposed, preferably with individualized and rich narratives. For example, some interviewees can answer most or all questions fluently and vividly. In these oral narration cases, individual stories flow into the flood of time, collectively presenting the changes of the times. This is an ideal state for the interviewer.

However, as perfect as it sounds, these interviewees are in short supply. When researchers roam the field, they meet different characters and hear different voices. Sometimes, their questions are unanswered, or some questions are selectively answered, or the answers supplied are not in reply to the question, sometimes answers arise without a question being asked, all of which form the different shapes of silent memories.

Among them, “questions unanswered” occur when an interviewer thoroughly inquires and inspires, but the interviewee will not share their thoughts, or will evasively respond with non-evaluative and non-personalized answers such as “it’s ok” or “it doesn’t matter,” which is a de facto “silent” reaction. Researchers encounter responses where “questions are selectively answered” in accordance with the nature of the question, the occasion, and people present, where interviewees display fragmentary silence. When “answers do not match the questions,” no matter what question the interviewer gives, the speakers have a set of answers prepared. They do not consider, or even ignore the question itself, they immerse themselves in their own world, trapped in the memory of a certain past fragment, which has the effect of silencing the interview question. Then, there are those interviewees who automatically tell their stories before a question is even proposed. Different from the “answers that don’t match the questions,” their narration is often based on past experiences. They have their own idea of how the interview might unfold, so they present themselves in a stylized way, which actually forms another type of silence, or we could say that enthusiasm replaces silence.

This reveals a great tension between questions and answers. So how are these silent memories formed? Behind silences, society’s cultural structure and research practices could be further studied. In the study of memory and oral history, the theoretical perspectives of power and culture have become mainstream explanatory paradigms. Some scholars have tried to find hidden paths of explanation, by exploring the deep structure of life, trying to liberate the “bound past” with “the glimmer of memory.” Based on following academic norms, this article argues that capturing silent memory must return to the context of time and space. Apart from physiological factors such as simply forgetting, society and cultural structures can influence and construct the silence of memory.

Why it happens

Oral history is set in a specific time and space, both of which directly contain context of the times, such as the cultural structure of society, and the interactions of power, culture, subjectivity, and other elements. Therefore, whether discussing the memory of events or people, the memory of the body or feelings, and the reflection of the memory itself, all these memories will be rearranged and displayed differently under different circumstances. As a group with cultural attributes, individuals express themselves in a variety of ways according to context.

Accordingly, different oral history presentations are the result of situational interactions between researchers and interviewees. In this dynamic scenario, accepted expressions include the dignified and implicit speech patterns, which hides details of private life and personal opinions, this presents the substantive silence of “questions unanswered.” It means, when the interviewees cannot determine whether it is safe to speak, they choose to lower their voice and hold their tongue.

Similarly, interviewees will also resort to episodic silence. Based on their own life stories, they organize their own version of stories that fit the time and occasion. In particular, when power dynamics shift, the narrator will selectively enlarge or tailor a memory. As a result, they sometimes put up a show to try and accomplish what they feel asked to tell. The performances of these “answers without questions” hide real memories in their silence and form a content-rich silence.

At the same time, avoidance of questions or giving answers that do not match are also quite common. These interviewees created and witnessed the history, so they cherish the moment when they are given the right to speak. When the microphone is handed to them, they pour out all the glory and greatness, injustice and misfortune of this life. By avoiding questions, they open up their heart, but also present an overall silence to the question asked.

It’s worth pointing out that the four types of expressions are not clear-cut but intertwined. The ambiguities and co-mingling among these responses not only exhibit the struggle of power, culture, and life within time and space, but also multiple variable forces in reality. In the end, all these differences comprise a silent memory.

How to capture silent memories

When the gate of time is opened and the hall of storytelling is prepared, the spectrum of memory gradually awakens, summoning an interviewee’s inner life. As a result, the characters, plots, and clues in these memories are given different arrangements by the narrator via substitution, conversion, suspension, concealment, appropriation, and silent moments. These silent memories convey either intense or calm emotions, some natural pauses, and some restrained fragments, which are full of the speaker’s subjective power. We should not only put these moments into the specific context of time and space to analyze their production logic, but also try to retain these memory symbols, to gain insight into the strength of silent memory from the perspective of power and culture. Then, how can researchers capture these silent memories?

To start with, we need to give voice to silent memories. Unlike a burst of narration, silence is the shadow of one’s memory. If we want to compare these two methods, we might visualize them as Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” and “Starry Night.” The former is burning of life while the latter is tranquil and deep. Though the two are different, they are without doubt full of strong emotions. Therefore, researchers can develop these memories by inserting background information, power dissolution, and multifaceted records.

Second, the absurdity or rationality of words and deeds depends on the specific limitation of time and space. Past memory and narration have specific temporal and spatial circumstances of power and cultural deduction. They jointly anchor the discourse world in which silent narration can be analyzed and give the narrator the psychological schema and a strategy of words and deeds. When time and space, as a container of relationships, are reproduced in text, the tangled and obstructed memory is gradually unlocked, and an individual silent expression is endowed with a breakthrough path from the edge of footnotes to the research center. Between the soft life experience and the hard social structure, the wall of silent memory reverberates loudly.

Observing narration through time and space is a journey where memory awakens and resonance is shared by researchers and interviewees. Therefore, in the process of explaining social and cultural backgrounds, the researcher metaphorically reveals the penetrating power of silence. The resistance, sadness, relief, and complex tangled silence will restore truth to life, so that readers can sense the power of silence—the silence will become self-explanatory.

Oral history is a work of art and technology, it aims to remove the pressure from conversations and reshape the power dynamic between interviewers and interviewees, to create an equal space that can be shared. To achieve this, the purpose of the interview, background research, data use, and privacy terms should be fully shared with the speaker.

In the meantime, the interviewer also needs to have a detailed understanding of the speaker’s life, so that both sides can construct a meaningful world. Oral narration is a progressive process, moving from pleasantries to depth, and from strangeness to familiarity. Interviewers are confronted with people who have complex social cultural attributes and history behind them. Therefore, researchers need to offer sincere emotional feedback to interviewees.

Next, the situation is not only constructed by power, culture, and the narrator’s deep life experience, but it is also now shaped by technology. Pictures, sounds, and video are useful in terms of giving new life to silent memories and repetitive retrospectives. We can see that through restoration techniques, the fading years can be restored. Through audio technology, sounds from the past can be heard. With the help of imaging technology, the past can be recreated and everything in the present can be preserved. Taking advantage of new technologies, limited records from the past can expand narration, while diversified records in the present can complement silences. Together, they fill the gaps in memory, enrich the forms of memory, and construct the three-dimensional pictures of the passing years. Also, the narrator’s facial details, vocal intonations, and physical movements can be recorded and amplified at any time. In the close-ups of narration, interviewees can take a closer look at their life, and researchers have more possibilities to uncover the truth behind silent memories.

The past is a prologue. In collecting these memories, individuals can reach a sublimation of value. Therefore, the practice and research of oral history is not only academic, but also ethical, moral, and is of profound cultural significance. As a text of memory, silence is also a powerful expression. It implies the depth of memory, like the sunlight shining through the cracks, leading research into the depths of time and space. In this sense, our exploration of silent memory and its diverse forms, especially the methodological discussion between silent memory and narration, will help to present multi-dimensional history in research and interpret the subtle nature of human nature, to integrate it into the evolution of society and human civilization.

Tao Yu is from the School of Sociology at Northeast Normal University.

Edited by YANG XUE

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE