History captured in images

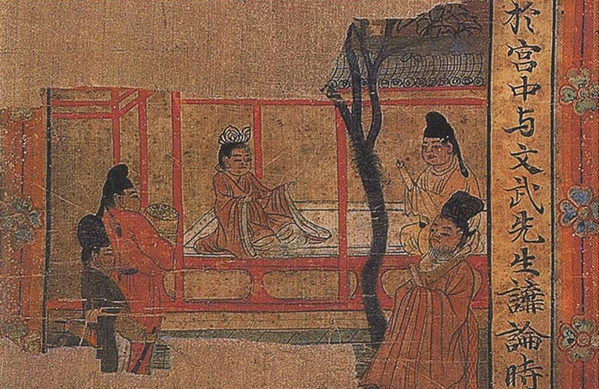

A Tang silk painting depicting Prince Siddhartha being educated in an imperial palace All photos: Courtesy of SHANG YONGQI

“Xingxiang Shixue” is a historical research project using ancient imagery as key source materials. Its main objects are the images created by human beings of ancient societies. Among the flow of civilizational elements along the Silk Road, the ones of concern for this project are the flow of images, as images of the same theme are often transformed by different civilizations in the process of dissemination, presenting us the scenes of the same theme under different circumstances.

‘Prince Siddhartha Heads for School’

In the field of Xingxiang Shixue, various image materials reflect people’s different understandings of the same characters, events, and scenes. The various “interpretations” of a Gandhāra schist engraving, “Prince Siddhartha Heads for School,” is a typical example.

Most of the extant scenes depicting children going to school in ancient times, dated at least prior to the Song Dynasty (960–1279), are about children of noble birth. The figure of discussion here is Siddhartha Gautama, the young aristocrat in ancient India who was carefully described in Hermann Hesse’s novel, and one of the “Die maßgebenden Menschen” [the people who matter] identified by Karl Theodor Jaspers. However, the scene we will “enter” is not one of the most glorious moments of Siddhartha Gautama’s life—the moment he reached enlightenment and became Buddha, or preached his sermon at ancient Indian cities—but rather the scene of him as a child heading for school. It is known as “Prince Siddhartha Heads for School.”

In this Gandhāra schist engraving unearthed from Charsadda Tehsil, Pakistan, Prince Siddhartha sits in a cart pulled by two bighorn sheep, and a driver holds the reins. The pine-cone-like fur suggests that the animals pulling the cart are sheep. At the front of the cart is a smaller lead attendant holding something in his hand; behind the cart under a tree are two attendants. There are four people at the top of the picture, larger than the abovementioned attendants. They are perhaps children studying with Prince Siddhartha.

Such an image shows the scene of an ancient young Indian aristocrat on his way to school in a luxuriously decorated upper class vehicle, and accompanied by specific schoolmates, also of noble birth. With the expansion of Buddhism, this story spread out of India, where it originated, traveled through Central Asia, and reached the Central Plain of China. The story, recorded in the languages used in the Western Regions at that time, was faithfully translated into Chinese without changing characters, scenes, and plots. However, its expressive elements began to change as the story was converted into images.

In a mural named “Prince Siddhartha Going to School” in Cave 290 of Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, dated to the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557–581), Prince Siddhartha rides on a horse. In front of the horse is a teacher in Chinese-style clothing. Behind the horse are two attendants, one of whom holds a hua-gai [a decorative umbrella used for Chinese emperors and nobles in ancient times, a symbol of power and social status]. The nobles of the Northern Zhou Dynasty preferred riding horses to sitting in carts, so Siddhartha is depicted riding on a horse and dressed as a noble of the Northern Zhou Dynasty.

In a Tang Dynasty (618–907) silk painting found in the Library Cave of the Mogao Grottoes, the scene of Prince Siddhartha going to school was altered, depicting a typical ritual scene of educating the crown prince in a Chinese imperial palace. Prince Siddhartha and his teacher sit on a ta [a traditional Chinese sitting platform], surrounded by court officials, noble children studying with him, and servants who tend to his daily life.

Along the Silk Road, the scenes of the same theme have undergone tremendous changes in the characters’ race, clothing, education methods, etc. The cart pulled by sheep was a symbolic vehicle for young aristocrats in ancient India. However, this vehicle was not recognized by the Northern Zhou people, let alone used as a symbol of social status. For people in the Northern Zhou Dynasty, the nobility of a character in a painting can only be discerned when the character rides on a magnificently decorated horse.

The highly developed etiquette system established in the Tang Dynasty did not allow Siddhartha, as the crown prince, to be educated at the home of his teacher. According to the Tang etiquette rule, a crown prince could only attend lessons in the imperial palace.

Evolution of lion motifs

In ancient civilization systems, a strict hierarchy was one of the crucial prerequisites for establishing social order. People including emperors, nobles, civilians, servants, and slaves had to be well distinguished in their political, military, and social life. Therefore, a visual hierarchical identification system of the ruling class, including houses, vehicles, clothing, and colors, was essential. Among them, lion motifs, which were used to symbolize kings in the western section of the Silk Road, evolved during the process of being introduced to China. This serves as a good example for understanding civilizational exchange.

In civilization systems centered around ancient India and Persia, the lion was the symbol of the king. Not only were the king’s seats often decorated with lion figures, but the king was also referred to as a lion. For example, Buddhist scriptures and other classics often describe Gautama clan members with terms such as “Lion King” or “Lion Jaw” [the paternal grandfather of Prince Siddhartha was known as Simhahanu rāja, literally meaning the Lion Jaw]. From the eras of ancient Egypt and Assyria to the Persian period, grand scenes of kings hunting lions were used to highlight their royal power and personal bravery.

This kind of civilization system, which used lions to symbolize the sacredness of the king, spread from West Asia to Central Asia, and then to the northwest of ancient China. According to ancient Chinese records, kings whose authority was represented by lions include the kings of Magadha, Gandhāra, and Licchavi, all of which were from the Indian subcontinent. The rulers of the Imperial Hephthalites and Persia, located between Europe and Asia, as well as the kings of Kucha and the Shule Kingdom in the present-day Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and the Tuyuhun Kingdom in the Qilian Mountains and upper Yellow River valley also regarded lions as a symbol of kingship. However, this cultural element had little effect on ancient China, where powerful traditional culture predominated. The influence of the lion as a symbol of kingship nearly vanished at the northwestern border of China.

The most dignified images of lions used in the Central Plain dynasties, still seen today, are the guardian lions usually found in front of government offices, Buddhist temples, homes of political or noble families, etc. They no longer embody the meaning of kingship as in the civilizations of the Western Regions. Even the manner of lions as ferocious prairie carnivores, their animal nature, has gradually turned playful and cute, making them auspicious motifs. The most typical example is the image of lions fighting created on a brocade by artists of the Western Regions in the Tang Dynasty.

In essence, both writings and images are creations of human beings. Elements such as kinship, gender, social identity, and hierarchical status require a large number of markers, among which images have been significant.

Shang Yongqi is a professor of History from the Ningbo University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE