Risk governance imperative in county-wide urbanization

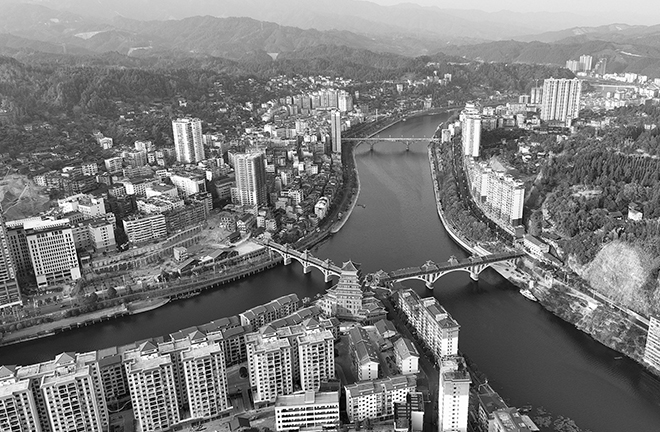

An aerial view of the Jinping County in Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province Photo: CFP

According to the Chinese governance philosophy, a stable and united nation depends on well governed counties. This logic reflects the profound value of county-wide urbanization. The urbanization of counties, which involves both urban and rural areas and concerns economic and social development, is the most direct structural carrier of national modernization. It is a process with rich implications, and the evaluation of achievements is based on results. The outcomes of county-wide urbanization can provide the yardstick by which the “footprint” of a nation is measured. However, it is imperative that social risks arising from this process be governed effectively.

Risk sources

County-wide urbanization proceeds with county-level urban areas and the vast countryside as spatial units and administratively associated elements, and focuses on the development of county seats. In terms of specific scope, it encompasses county areas different from large and medium-sized cities and city clusters, featuring explicit governance standards. Its content centers on county seats as well as urban-rural interaction and integrated development of urban and rural areas. It is, by nature, a bond linking urban and rural areas and a holistic social process based on the development and protection of individual rights and interests.

Emergent risks of county-wide urbanization can arise due to the selected model for governing complex objects. Counties differ considerably from one to another. In terms of county seats, they can be divided into five major types, including those close to metropolises, those with an industrial edge or specific functions, agriculture-intensive ones, those of ecological significance, and those suffering from population outflows. The chosen governance model must be customized for the different types. From the perspective of the government-market relationship, there are significant differences in the approach to and extent of resource allocation for the urbanization of such diverse county seats, so governance models should be flexible and adjusted accordingly. A “one-size-fits-all” approach will escalate and complicate social risks.

Second, risks arise from overlapping domains in county-wide urbanization. Dealing with various longstanding issues at the same time is particularly prominent at the county level. In the governance of multiple domains, including the economy, society, culture, space and ecology, problems of “overload” and “imbalance” coexist. Efforts have been made not only to address “semi-urbanization” [or inadequate urbanization], and improve the quality of urbanization, but also to engage in re-urbanization—to upgrade the functions realized in the previous round of urbanization. Also efforts in “urban renewal” and “urbanization of the people” have been made, respectively, to optimize carriers, and to ensure rural migrants integrate into urban society and safeguard their rights and interests. Organically sharing the costs for the integration of industries into cities, social security, public services, and the migrants’ assimilation is even more complex and tricky.

Third, the solutions to problems associated with county-wide urbanization also present risks. Problems pertaining to basic elements, such as population, land and capital, have long been fundamental to county-wide urbanization. Specifically, we have had to confront issues such as population inflow and outflow, where land should be claimed and used, and where capital should be withdrawn and spent.

Nature of risks

As a mark of modernization, county-wide urbanization is a comprehensive public agenda. It is a process of social progress that aims to ease and dissipate contradictions between urban and rural areas in economic and social structure. However, the process involves extensive and profound transitions to modes of thinking, production and life to align with a typical urban society. As mutual adaptation between rural transformation and urban development progresses, a myriad of risks will accumulate due to social structure tensions.

Representative social risk theory argues that risk governance addresses the continuums of “social risks vs. public crises” and “realism vs. constructivism.” From the perspective of public administration, managing social risks has three orientations. The first orientation is a disaster perspective, beginning with particular incidents, and stressing technical management. The second is a crisis perspective, focusing on the impact of such incidents on people, which emphasizes institutional and administrative means, as well as people’s psychological adaptation to tackle threats from both inside and outside. The third is an emergency perspective, with the anomalous nature of incidents as a point of departure, highlighting the contingency of public administration.

County-wide urbanization includes a systemic transformation of economic and social structure. Though it is an important force driving China’s modernization, this process also harbors a wide array of risk factors which are likely to undermine social harmony and stability across the county and the whole nation at large.

Large-scale urbanization of counties would result in imbalanced temporal-spatial and social structures. Therefore, risks of county-wide urbanization are essentially risks from adapting to structural changes. They arise from multiple sources, involve multiple fields, and occur at different levels. This conclusion is based on two vital facts.

First, at the basic level, the continuous massive migration of the agricultural population to county seats nearby will become commonplace, particularly in the vast central and western parts of China. This will accelerate the accumulation of social risks within county seats, which are transitional areas between cities and townships.

Associatively in villages, as relative to county seats, extensive economic structural transfer, restructuring of village governance, reshaping of rural cultural identity, and reconstruction of social order occur simultaneously but not synchronically. This invites many problems with regards to “rural reproduction,” involving multiple social and economic dimensions. In general, risks in county-wide urbanization are by nature those of structural adaptation in the process of social progress. In essence they are social risks from process-oriented reconstruction of rights and institutional governance.

Suggestions for risk governance

Attention should be paid to overlapping risks in county-wide urbanization. The first type of risk concerns the survival of residents. To preserve the basic standards of living for residents, it is crucial to ensure stable employment, housing, elderly care, medical care, and food security, guarding against risks that may arise in these aspects for various reasons.

Second are development risks, referring to risks of conflicting social interests among individuals, families, and groups, and damages to personal and property security. They arise from disruptions to the original structural and environmental equilibrium, due to land expropriation and demolition, safety production, environmental protection, transitioning from old to new development drivers, and market fluctuations.

The third are value-related risks which may arise from shifting social norms and values. These can include social identity crises, a sense of inequity or injustice, moral disorders, and social anxiety.

The fourth type of risk is related to order. In particular, the normal states of social production, life, and operation are threatened and destroyed, leading to social disorder, mistrust across society, and difficulties in social interaction and communication.

It is worth noting that these types of risk are not independent from each other. Overlapping and intertwined, under certain circumstances they may instantiate each other, further jeopardizing social security and stability county-wide.

It is likewise necessary to explore how social risks in county-wide urbanization emerge and transform. The processes by which social risks are generated in county-wide urbanization have commonalities, and the rationale behind risk re-generation, transfer, and upgrade is subject to the intrinsic logic of “structural tension leading to conflict behavior.” It is crucial to delve deep into the ever-changing urban-rural social structure at the county level, and take note of changes in spatial processes of county-wide urbanization and resultant shifts in models of production, life, and thinking. Mitigation of early-stage risks, mid-stage risk transfer, and later-stage upgrades into crises, as well as their internal mechanisms, require in-depth analysis.

Going further, efforts are needed to build a mechanism for deep governance of social risks in county-wide urbanization. Artificial, correlated, and dispersive, these risks have something in common with social risks present in large and medium-sized cities and city clusters. They also have distinctive features that are inseparable from counties’ administrative systems and spatial units. It should be emphasized that the reality of social risks accumulated from rapid urbanization indicates the necessity to upgrade superficial mechanisms which focus on emergency response to also cover management of public crises and risks. A people-centered approach must be taken to form a full-cycle social risk public management system for county-wide urbanization.

It is inadvisable to limit the governance of social risks to managing emergencies and responding to specific incidents. Deeper-level problems will never be effectively solved by doing so. Problems arising from the urbanization of rural migrant workers, the integration of industries into cities, the protection of rights and interests, and expropriation of land and demolition can only be managed by constructing a grand vision, systems thinking, and robust institutional mechanisms. Other issues such as “NIMBY” conflict, identity crises, and low levels of social participation may also be addressed in this manner. Therefore, it is essential to seek ways to organically and systematically integrate “semi-urbanization,” “re-urbanization,” “urban renewal,” and urban development, and build an economic and social ecosystem that can bolster the healthy and sustainable development of county-wide urbanization, thereby forming a long-term mechanism for deeply governing social risks.

Huang Jianhong is a research fellow from the Center for Chinese Urbanization Studies at Soochow University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE